Exercise is great but exercise studies...not so much

Two observational studies on exercise gained significant attention on social and regular media. I argue that both are flawed and therefore wasteful

I have long felt that we don’t need more evidence for the benefits of regular exercise.

For many reasons, not least because a) it is biologically obvious that humans were made to be active; b) exercise not only helps the body but also the mind; c) everyone knows very old people who achieved very old status in no small part because of a daily exercise habit.

How much, what type and for how long should exercise be is like asking how happy a person should be for optimizing health. It’s as silly as it is unknowable.

Yet epidemiologists must not be busy enough because they persist in publishing 5000+ word manuscripts on exercise.

In essence, exercise studies most often take big databases of people who have been followed for decades and correlate their reported exercise or measured exercise with outcomes. As if everything else that could affect lifespan can be adjusted for by a computer algorithm.

The BMJ published one such study. Harvard researchers asked whether different types of activities have distinct associations with mortality, and does varying your types of exercise provide more benefit?

They had large numbers. All these studies do. People had hip worn accelerometers which were able to assess 9 different activities (walking, jogging, running, cycling, swimming, tennis, stair climbing, rowing/calisthenics, weight training).

They then created a “variety score” which scored the number of different activities done above a set threshold.

The first finding was that most individual activities associated with a 10-17% lower risk of death—except swimming. Grin. Swimmers don’t live longer.

The second finding—the one that got the most attention—was that a higher variety score associated with 19% lower all-cause mortality, independent of total activity volume.

Note the causal language in the authors’ summary

Overall, these data support the notion that long term engagement in multiple types of physical activity may help extend the lifespan.

The Lancet published another big exercise study whose question would center on small realistic increases in physical activity or decreases in sedentary time.

This group analyzed 7 cohorts with hundreds of thousands of people. And also used accelerometers to quantify exercise. They calculated a “potential impact fraction” or PIF as the proportion of deaths potentially preventable.

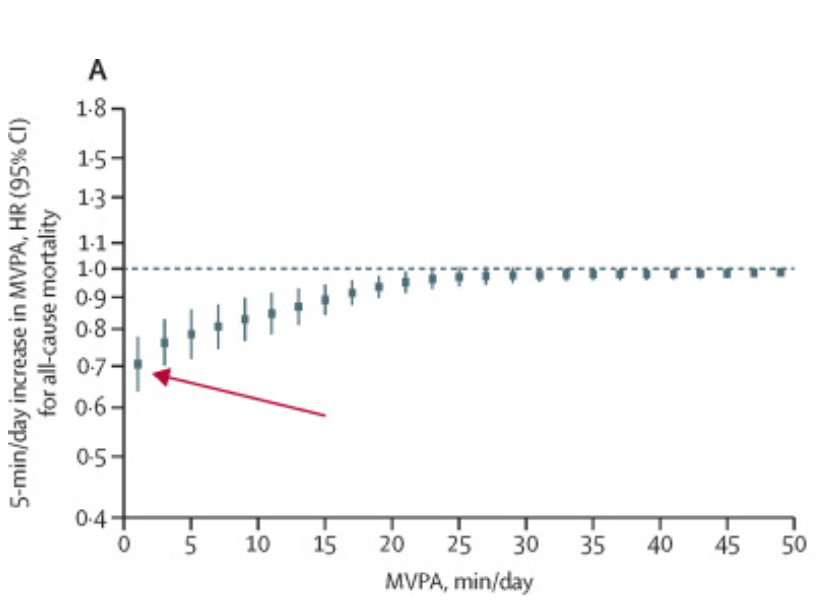

They found that a 5 min/day increase in moderate-vigorous physical activity led to major reductions in the chance of dying. It’s effect was greatest in those who had the least level of activity.

The picture below shows that going from 1 to 6 min/day reduces death by 30%. But if you already do 30 minutes per day, you get no benefit from 35 minutes.

This study also showed that those who reduced sedentary time had similarly large reductions in preventable death.

My Comments

I am sure you could add to my list of problems, but here are the issues that come to my mind.

Plausibility

It’s easy to believe that exercise or physical activity is beneficial over a lifetime, it’s hard to believe that 5 min/day (the equivalent of walking 400 meters) reduces death by 30%. That’s ridiculous. That it is taken seriously by the authors speaks to their disconnect from reality.

Similarly, in the BMJ study, they say the act of doing different types of exercise is all that you need to do. It doesn’t matter if you exercise 10 min or 60 min per day; just do different types of exercise. This, too, is a the opposite of common sense.

Analytic Flexibility

In what is perhaps Sensible Medicine’s most important post and podcast, the group of Dr. Dana Zera Zeraatkar have shown that these sorts of studies have many thousands of analytic choices—each of which can affect results. For instance, their group showed that data on red meat consumption and death could output any manner of results depending on analytic choices.

These papers overflow with analytic choices, such as the many covariates to adjust for, the thresholds of variety of exercises and the “stopping updates after disease diagnosis.”

To take a specific example from the Lancet paper on adding 5 minutes: when they looked at the association in the UK Biobank cohort alone the effect was much smaller than overall. Why? Who knows but that it differed speaks to the noise in these studies.

Confounding

In every lookback study like these, researchers find associations.

People who do this or that live longer or shorter. The problem is that besides this or that (in this case, variety of exercise or adding 5 minutes), they do 10,000 other things. Some of these can be captured on spreadsheet and be adjusted for but most cannot. So you don’t know if people who vary their exercise also eat better or have more money or live in neighborhoods with less pollution or have fun jobs, or gulp, also eat blueberries, because surely blueberries extend life!

These studies find correlations, but the leap to causation (and hence action) is huge. Or should I say impossible.

Both papers linked above are open access. You can look at how much work went into each.

The authors collected data from public databases, crunched numbers, had zoom calls, wrote narratives, replied to reviewers to publish this work. It was a huge effort.

But to what end? The data is flawed. The associations don’t get in the same neighborhood as actionable.

Why do people do this sort of thing? The BMJ study came from an NIH grant. The Lancet study reported no external funding, but most of the databases that they used are publicly funded.

Is this a good use of public funds?

I do not mean to imply that all observational work is worthless. It is not. But these sorts of studies looking at exercise seem wasteful.

P.S. I scanned the Altmetric views of these papers. Hundreds to thousands of media outlets and social accounts covered the work. As far as I can tell on cursory review, Sensible Medicine is the only one with critical appraisal. Yet another reason to support our effort. Thank you

Good observations. For the most part, diet studies can be assessed the same way.

Great review! There are all these studies on exercise - morning or afternoon, this exercise or that one. My advice to others that the best exercise is the one you can stick with, no matter when you do it or what type you do. And also to get up a move frequently throughout the day - unfortunately my trips are most commonly from my office to the kitchen :) . Common sense should prevail. Maybe they can use the money to fund studies related to women's health instead, which has been neglected for far too long.