Flawed Studies Teach Us a A Lot

As it is in math, repetition enhances learning. This week, we go over the problems with nonrandom comparisons, so called observational studies.

The journal JAMA Network Open published an attempt to sort out the best stroke prevention strategy in patients with kidney failure and atrial fibrillation. It did not work, and the lessons are instructive.

The first thing to think about would be how you would properly answer this question.

The correct way would be to randomize patients to one or two or three of the strategies and then measure an outcome. Randomization would balance known and unknown differences in baseline characteristics. In the end, you would have isolated the therapy as the only difference, and then you can infer causality regarding outcomes.

That is not what the authors did. Instead, they harnessed data from a registry; looking at outcomes after two different treatments.

The core problem with that strategy is that a clinician chose the strategy—not randomization. The factors influencing that clinician were surely not random. And those characteristics often (probably always) affect outcomes, thereby making inferences about the two treatments nearly impossible.

The specific questions and background of this study:

The clinical problem involves patients with end stage kidney failure and atrial fibrillation. Most Sensible Medicine readers will know that one of the major tenets of AF treatment is stroke prevention—usually with oral anticoagulants (OAC).

The evidence underpinning anticoagulation dates back to the warfarin days in the 1980s. RCTs of warfarin vs placebo or aspirin in patients with AF showed clear dominance for warfarin. Years later, direct acting oral anticoagulants (DOAC) were shown similar or better than warfarin.

A few years later, proponents of left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO) proposed that plugging the appendage could be a reasonable alternative. I, and others, disagree, but our opinion is a minority.

The presence of kidney failure requiring dialysis radically changes all of the above background information.

I would argue that almost none of it applies. For numerous reasons: a) none of the trials supporting OAC included patients with severe kidney failure, b) two trials have been attempted in patients with kidney failure but each had inadequate power to sort signal from noise, c) patients on dialysis have a much higher rate of major bleeding (due to platelet dysfunction), d) kidney failure alters drug clearance making dose selection challenging, and e) for every observational study you can find showing that OAC reduces stroke, I can find you one showing that OAC increases major bleeding. Without RCTs, we can have no evidence-based prior beliefs.

The Study in Question

The authors chose 2344 patients who developed AF after beginning dialysis (mostly hemodialysis). One group of 293 patients received LAAO and 2051 received OAC. These are obviously unmatched non-random groups.

The primary outcome was all-cause death. Secondary outcome was stroke. Safety outcome was major bleeding.

Before moving forward I should express two major worries.

One is the unmatched groups. One has nearly 300 patients and the other 2000. There were other baseline differences as well, but let’s address this a bit later.

The second worry is even worse: the choice of death as a primary outcome is wrong. We know from a very nice trial called LAAOS-3 that surgical closure of the appendage vs no closure in patients with AF who were having heart surgery for another reason reduced stroke by 33%. But that huge reduction in stroke was not enough to reduce death. The reason is that while stroke is an important thing to avoid it is not a large enough cause of death to reduce overall mortality. For instance, stroke causes only about 10% of deaths.

Back to the study.

The challenge the authors faced is to match patients in the two comparison groups (LAAO and OAC). There are many ways to attempt this. They chose propensity matching, which is a way to find patients who look alike based on characteristics in the datasheet.

Recall that some things (age, sex, history of HTN or diabetes) make the data sheet. But other things do not—namely the general appearance of the patient or their home situation or the mental status.

The main results:

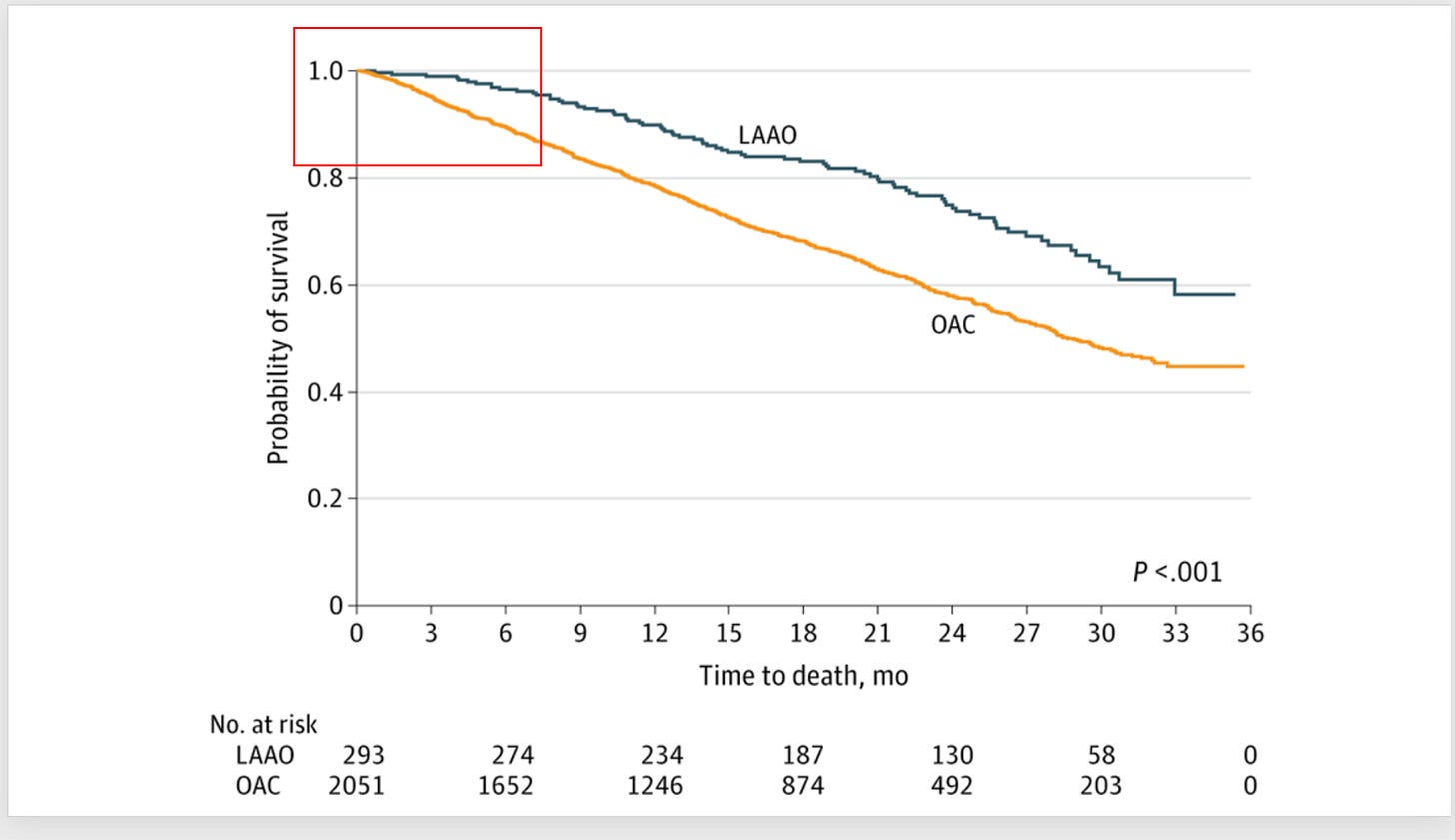

The picture shows that patients in the LAAO group had a much better survival.

HR was 0.47 (95% CI 0.30-0.72). I added the red square, which shows immediate separation of the survival curves, implying that LAAO confers an immediate survival advantage.

Recurrent bleeding was also lower. HR 0.74 95% CI 0.56-0.98.

Nonfatal stroke, however, was not reduced when fully adjusted. HR 1.18 (95% CI 0.76-1.81).

The authors concluded:

These findings suggest that these data should be considered in shared decision-making in consideration of LAAO for patients with KF and AF.

Comments

I show this study because of its fatal flaws.

No matter your opinion on LAAO, everyone agrees that—if present--the stroke and bleeding reduction accrues over years not weeks. And LAAOS 3 shows that even a 33% reduction of stroke with surgical appendage closure was not enough to budge survival.

This paper purports to show immediate survival advantage from LAAO. This is almost certainly impossible. The reason these curves separate immediately is that clinicians chose healthier patients to receive the device, and matching was unsuccessful in sorting this out.

The authors admit to “fundamental limitations” of their analysis. But then write

Despite these limitations, with the rapid clinical adaptation of an LAAO device in this patient population and a prior RCT that were limited by poor recruitment, large prospective registries such as ours can therefore fill the void in evidence until future RCTs conclusively prove the superiority of LAAO over OAC in this patient population.

I could not disagree more with this conclusion. “Rapid clinical adaptation” of anything is not evidence.

And as for observational studies: their finding of immediate survival benefit with LAAO proves that it is impossible to sort this question out with nonrandom comparisons.

That they and the editors and peer reviewers don’t realize this is worrisome.

As for the clinical question of stroke prevention in patients with both kidney failure and AF, I believe we should first answer the more basic question:

Does OAC have any role over placebo in the patient with kidney failure and AF. I strongly suspect such a trial would show no benefit. It’s sad that it has not been done.

It would appear that the authors demonstrate significant motivated reasoning. Could it be that those performing the LAAO procedure are benefiting the most from widespread adoption?

I started reading this study and stopped when I read the methods. It was either designed by a med student or mathematician being intentionally obtuse