Friday Reflection #26: General Internal Medicine in the Time of COVID

MJ is a 24-year-old man who presents to his primary care physician on March 16, 2020 with fever, myalgia, and sore throat. He recently came home to Chicago from New York City after his college sent the students home.

My career has been bracketed by an epidemic and a pandemic. And yet, as I search these reflections, I’ve typed HIV or AIDS 48 times and COVID a mere 3. Why is that? On a personal level, I just want to be done with COVID. I have no desire to revisit the days of fear and uncertainty, the disruptions to my children’s lives, and the closing of the Chicago lakefront. Professionally, I have other reasons to not want to look back. Among them is how those early days of the pandemic undermined so many of the reasons that I love my work.1

Now, I realize that 2000 words on how COVID affected me, personally and professionally, when I lost only a few patients and no friends or family will seem insensitive, aggravating, and downright infuriating to some. Believe me, I get that. It is probably part of why I have written so little on this topic. If you could care less how privileged Adam Cifu feels he was professionally tormented by COVID, read no further.

As the best way to organize this piece is chronologically, it is a helpful reminder to review the waves of COVID activity – apologies for the triggering potential of this graph.

March 2020: COVID strips a veteran physician of his invincibility.

Early 2020 was scary. The news out of Wuhan and our experience with SARS and MERS made it clear how bad the pandemic could be. Owing to a collaboration with the Wuhan University Medical School, I had visited Wuhan in 2008 and 2017. I’d been in the hospitals that were being overwhelmed and worked with the doctors who were first on the front line. In 2017, I’d even spent a day knocking around one of the city’s wet markets.2 These contacts and experiences added to my anxiety.

Next came the news out of New York City, my hometown, where my doctor friends lived the overwhelming scenes inside hospitals and my non-doctor friends listened to the constant ambulance sirens and lost older friends and relatives.

In Chicago, we planned for the inevitable wave. I had to choose what role I would play. I was torn between throwing myself into inpatient work and acknowledging that my age and medication-induced immunosuppression probably made that a poor choice. As our hospital filled up, I was left doing video visits with my patients (visits that I found unrewarding), educational sessions about COVID for doctors from other specialties, and urgent care shifts to see the patients who needed to be seen in person.

MJ was the first person I diagnosed, definitively, with COVID. Never was there less of a diagnostic dilemma. Memorable was how different our behaviors were compared to those of a doctor and a patient during any previous visit for an “influenza-like illness.” He was masked, I wore full PPE (mask, goggles, gown, gloves, and bonnet). In addition to feeling physically terrible, he felt guilty that he had become sick and would put his family at risk. I was a little nervous seeing him but also excited to see the disease, clinically, up close. (MJ did fine and nobody else in his family was sickened).

These weeks marked the first time in my career that I feared getting sick. I lost the invincibility of my youth. Even worse, I felt that my skills were not needed. I felt guilty for not joining the inpatient fray. I was not able to do the work I love and felt undeserving of the gratitude being directed toward doctors.

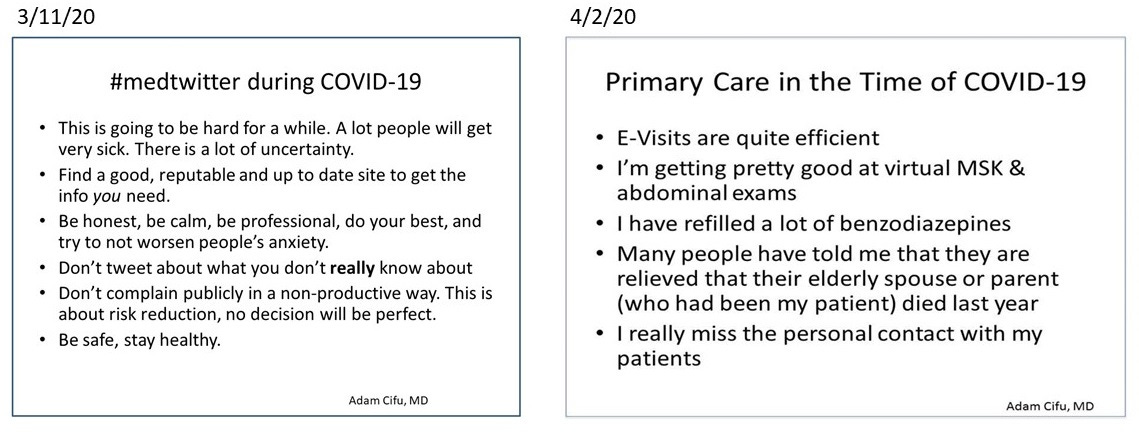

Two of my tweets from this period speak to my anxiety and how conflicted I was in my practice:

May 2020: Back to work, but not the right work.

As April turned to May, we had figured a lot out. I had given up the virtual clinics in favor of my usual practice. I had pored over a website, recommended by my gastroenterologist, on which IBD docs reported their patients’ COVID outcomes stratified by their medication. This convinced me that I was safe to join the inpatient teams.

I was happy to help, but I mostly just felt like a warm body on those teams. As a non-intensivist, I didn’t feel like I was adding much to the medicine. At this point in my career, what I bring to an inpatient team are my diagnostic skills and my ability to work with families and colleagues. These skills did not feel critical.

July 2020: A reprieve.

June and July of 2020 felt like February 2020. Case rates were low. My usual July inpatient stint included little in the way of COVID care. However, we were fully aware that we’d be seeing more cases come fall and winter.

Fall 2020: OK, I do have a role.

By the fall of 2020, I began to find my bearings. Having weathered six months, caring for dozens of patients with COVID – inpatient and outpatient – without getting sick, my feelings of invincibility were returning. I was also gaining the experience that makes primary care doctors valuable; I was managing the denominator. Instead of seeing only the patients who ended up in the hospital, or the ICU, or on a ventilator, I was seeing and speaking to all of my patients who had so much as the sniffles. I realized that if I got sick, the overwhelming likelihood was that I would be fine. Of all my patients who’d been sickened, only one – a frail 93-year-old man – had died. Only he, and one other of my patients, had even been hospitalized. Anecdotes yes, but like the actual data, they affected my mindset.

I also began to feel useful as a physician and an academic. Applying evidence-based medicine (incorporating medical knowledge, clinical experience, and data from systematic research) to people I knew well, made me recognize that what I do, and what makes my job satisfying, had a role. I could advise my patients on preventative strategies and on what to do when they became sick. I gauged people’s vaccine hesitancy and then strengthened our therapeutic alliance by being honest about who absolutely needed vaccination – those for whom hesitation was senseless, even dangerous -- and those who had the luxury to make their own decision. There were conversations about which activities carried high risk of infection and how to balance the value of activities and risks.

We also began to see data about treatments and vaccines and I could help appraise the literature. On the inpatient service, I was able to bring healthy skepticism to what we were doing. I could determine when, and in whom, novel treatments like dexamethasone and remdesivir were effective and when we were using them to treat ourselves rather than our patients.

The conversations I felt especially privileged to have were those that people felt comfortable only having with me. These were with people who were making objectively irrational decisions. Some were isolating although they were relatively young and healthy, vaccinated, and living in times of low infection rates. Others were people at the highest risk for complications of COVID who declined vaccination and insisted on living as though the pandemic did not exist. Though my initial reactions to these conversations was often irritation -- I wanted to say, “what is wrong with you, get back to your life” or “do you not believe that the hospital is filled with people just like you with COVID” -- these discussions revealed the complexity of people’s decision-making. There were people who admitted that the pandemic had given them license to live the introverted lives they always wanted. There were people whose fear could only be handled by denying that the health emergency was real.

January 2022: Back to “regular medicine”

Like in so many places, January 2022 was a tough period. Our hospitalization numbers dwarfed those of spring 2020. I volunteered for an extra inpatient stint to cover a service created just to take care of the COVID admissions. I worked with one resident, our marching orders were just to get the work done. It was a relief, at this point, to feel that caring for patients hospitalized with COVID felt no different than caring for anyone else in the hospital.

I am profoundly lucky that COVID affected me most in lessening how fulfilled I felt at work. I have a job that readily offers respect, privilege, autonomy, balance, and wonderful colleagues. The pandemic managed to chip away at all of these. At the start of the pandemic, I worried that the respect, privilege, and gratitude that my career afforded me was undeserved. The degree of professional autonomy I enjoy enabled me to work how I thought I should in March and April 2020, but also set me up for guilt that I was not doing more. I never think about work-life balance. I work hard at what I love, find it easy to step away, but am seldom bothered when I am called back to work. In the early days of COVID, I felt I wasn’t needed. With less productive work, and kids at home, my balance was lost. Lastly, I work with amazing colleagues whom I missed as we tried to isolate as much as possible, hoping to preserve our personal protective equipment and ourselves.

There are things that I wish I had done better. I was proud of how I counseled people (patients, friends, and family) who were not taking the pandemic seriously. But, if I had it to do again, I’d hope to be as convincing as I was vocal. Later in the pandemic, I could have been more empathic for those whom I counseled that they could let their guard down. Although this counseling was always meant to help them, I should have reminded myself that everyone had reasons for their fear, which were often very personal. I wish I had never accepted the idea that we would achieve “herd immunity” through vaccination (or a combination of vaccination and infection). That has never been achieved with a coronavirus, why should SARS CoV-2 be any different?3 I am sorry that I parroted those who should have known this truth even better than me.

I remain proud of the very few things I wrote and shared publicly. These reflected my uncertainty and desire for the debates to be less heated. In an OpEd for the Chicago Tribune I wondered if there was a way to find understanding in our disagreements. In three pieces for Sensible Medicine, I wrote about the how we might manage masking in healthcare settings, debated pediatric vaccination, and reported how I was managing my personal risk. I should have engaged less with people whose public pronouncements about COVID came less from a place of honesty and caring and were instead based on fear, personal trauma, or attention seeking.

Thirty-nine months since seeing MJ, my reflections on these times are not yet “mature.” I do know that I erred in thinking that my skills and abilities were inconsequential to the care of patients. I made the mistake of feeling that I needed to do something new rather than apply what I do well to a novel situation. I think many people learned this during the pandemic. Craft distilleries produced hand sanitizers, tailors made masks, and companies making a few dozen helmet ventilators ratcheted up production. I certainly hope I will not have to face this situation again. But, there is clearly something valuable about learning to adapt my skills to novel situations.

I guess in today’s parlance you could say I am suffering from urgent normal syndrome.

That is the kind of activity that I consider enjoyable after a morning in meetings or on rounds.

Though immunity has, of course, turned COVID into a minor threat.

It is a pleasure to hear from a doctor with the grace to show some humility. This is something that was sorely missing during the past 3 years. Even today in the comments on this site you see MDs essentially saying “Shut-up you ignorant plebe. You have no medical training how can you dare question what you have been told by your betters.” Many of the things we did in the panic at the onset of the pandemic was contrary to common sense and past experience. These included a lack of consideration for natural immunity, universal masking (with cloth masks?), no consideration for the age of patient, pursuit of universal vaccination during a pandemic for a fast evolving respiratory virus, quarantine of the healthy, etc. The medical profession has taken a big hit to its credibility, when we needed our medical professionals to be rational and reasonable they responded with outright panic and irrationality. I would caution doctors not to take their patients polite nature and desire to move on as acquiescence and agreement. One only has to look at the complete collapse of Covid vaccination rates while the overwhelming majority of medical professionals were still advocating vaccination and boosting to see that many patients recognized the folly of the advice they received and made their own decisions. Also, look at the declining rates for all vaccination or polling of the public showing significant decline in trust for the medical community. I feel badly for the doctors who stepped out and tried to advocate for their patients only to be slandered by their peers and threatened by their professional organizations and employers. However, there were far too few doctors and other medical professionals who did so. What went wrong in the medical profession that allowed this situation to occur?

I appreciate your take on this but I must admit it leaves me with questions--As your colleague Vinay Prasad has posited, masks don't work in situations like these. No data supports that. So why would it be praise-worthy that people made more of them? Ventilators too turned out to be problematic as nearly everyone that was put on one (my own mom included) did not survive that experience. So why should it be praiseworthy that we allowed our government to convince companies to drop what they were doing and make more?