Friday Reflection 34: Disagreement and Chagrin in Therapeutic Decision Making

PP is a 67-year-old woman who comes to clinic with six weeks of progressive weakness. She feels aching in her buttocks, thighs, and shoulders. She is unable to rise from a chair unassisted and can walk only if supported by a companion.

PP has a long history of hypertension and type II diabetes, both well controlled. She has coronary artery disease and had stable angina until she started an appropriate medical regimen. Her current medications include metoprolol, chlorthalidone, potassium chloride, isosorbide mononitrate, metformin, atorvastatin, and aspirin.

If I were to make a pie chart of what I do in the office, there would be slices for counseling, diagnosis, and therapy. Most counseling happens during the visits themselves. Diagnostics are probably split 50/50 between the histories and physical examinations performed in the office, and the diagnostic tests and procedures for which I refer patients. My therapeutic interventions are mostly done by me in the office. I might refer 20% of issues out — for surgical procedures, physical therapy, or medical interventions that are not part of my scope or practice. The therapeutic interventions I provide are overwhelmingly pharmaceutical. There are the occasional office procedures, but mostly, if I am going to intervene on someone’s behalf, it will be done by applying pen to prescription pad.1

With any of these interventions, a conversation precedes the prescription. I suggest what is indicated and discuss the strength of that indication. My patient responds by telling me if he is disposed to accept my recommendation. This is the essence of shared decision making. I am the one who determines what makes sense medically. My patients consider how my recommendations fit with their values, philosophy, and lifestyle.

When I first learned about shared decision making, I was taught that when patient and doctor stay in their lanes – doctors say what is or is not indicated and patients express their preferences – things tend to go well. When the doctor and patient stray into each other’s lane, conflict often follows. This is the doctor who explains why, at age 80, it would be crazy to be “full code.” This is the family who demands dialysis for a loved one whose heart, liver, and lungs – in addition to her kidneys -- are failing.

Over my career, though, I’ve learned that the smoothest negotiations happen when each driver ventures, cautiously, into the other’s lane. A doctor has some sense of a patient’s values and incorporates this into her counseling. She still discusses an option the patient likely won’t accept, acknowledging that it is “probably not something you’d choose.” Patients are pretty much expected to wander out of their lane these days. Most of my patients have a sense of what they want done when they enter the office.

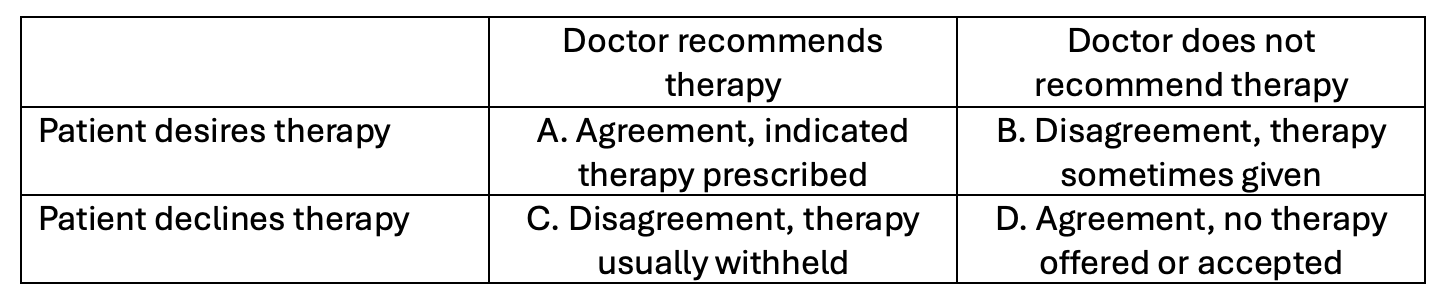

Even with this model, however, there is no shortage of disagreement before initiating therapy, and chagrin afterwards. Like most complex phenomena, this can be reduced to a 2X2 table.

The easiest visits are described in “Cell A”. There is a clearly indicated therapy and the patient wants and accepts the therapy. The angst in this cell only comes later if the therapy fails. What we consider “gospel” in medicine, especially in internal medicine, does not benefit most patients. Although we agree that beta blockers or statins are indicated post MI, and we know that a population treated with these drugs do better than one in whom they are withheld, most treated patients do not realize a benefit.2

Worse than the person who does not benefit -- the person on a statin who has an MI or the person who got the Covid vaccine and still ended up in the hospital with COVID -- are people harmed by an indicated and accepted intervention.

A doctor who had not offered my patient, PP, a statin would not have been doing his job. She had coronary artery disease, an absolute indication, in addition to other illnesses that put her at even higher risk. Her decision to accept my recommendation was also unremarkable – the reasoning and data behind the recommendation was clear and she had benefited from similar therapy in the past.

Statin-associated immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy is a rare complication of statin use. It is thought to be an autoimmune disease due to antibodies to HMG-CoA reductase in regenerating muscle. We diagnosed PP with the disease quickly after she presented with proximal muscle weakness and elevated muscle enzymes that failed to improve after she discontinued her statin. However, it took three years of immune-suppressant medications before she had fully recovered.

“Cell B” contains visits that include honest and clearly expressed disagreements. During these visits, a patient requests a therapy, one for which they need a doctor’s order. The desired therapy is one that I truly feel is not indicated and might even be harmful. These may be patients who want to be screened for prostate cancer at an advanced age or want to begin a statin despite youth and normal lipids. One patient, whom I remember well, fervently desired higher doses of opiates for pain that was not responding to opiates.3

The opposing forces in these visits are obvious. The patient is stepping into my lane, asking to be the prescriber, the medical expert. I recognize that is wrong, but I also recognize that it is the patient’s health and thus, if they really understand the balance of harm and benefits, is there a reason to withhold what they want? Maybe prescribing the non-indicated therapy and preserving our relationship is the right answer in the long run.

And then there is the “chagrin factor,” a term coined by Alvan Feinstein in the mid ‘80s. Feinstein used this term in very particular ways, which I generalize here to encompass that retrospective unease for having done the wrong thing. The chagrin you feel after a patient suffers a complication of a clearly non-indicated therapy that you prescribed because a patient asked for it is pretty great.

“Cell C” visits are irritating but not particularly difficult. Patients sometimes decline indicated therapy. My efforts at convincing a patient to accept a recommendation depends on how important I feel it is. I will dance on a table to get someone to quit smoking. To convince someone with a 10 year cardiac risk of 13% to begin a statin for primary prevention, I will doff my dancing shoes and engage in a conversation that sounds more like this:

Me: Because your risk of experiencing a cardiovascular event (heart attack, stroke, new angina, sudden cardiac death) over the next 10 years is 13%, you would benefit from a cholesterol lowering statin medication. I would start 10 mg of atorvastatin daily. What do you think?

Pt: Don’t the medications have side effects?

Me: They are generally very well-tolerated medications, and given your cardiovascular risk, the benefits greatly outweigh the harms.

Pt: I don’t think I want to take it.

Me: OK.

The chagrin factor here is lower because, if something goes wrong, I have committed the sin of omission, rather than the sin of commission committed in “Cell B”.

I think there is a career worth of studies to do on cells C and D. I wonder how the patient doctor relationship, issues of equity, race or gender concordance affect the outcomes of these conversations.

The conversations in “Cell D” are mostly ones that do not occur. I am not recommending a therapy, so a patient does not have the opportunity to accept or decline. Sometimes a patient will ask about taking something, but they are not committed to it. A brief explanation that Jamaican noni juice will not cure their hypertension usually ends the discussion.

Therapeutic decision making resembles a dance. Each partner has a role to play. The dancers may be comfortable with some steps, but not with others. One partner may choose to lead while the other may or may not be willing to follow.

Yeah, I know, it is actually keying a medication order into EPIC but I liked the way that sounded.

I’m using the number needed to treat (NNT) here, an approach to data that makes some people cringe. The NNT to prevent the primary outcome – death or MI – in patients after MI for statins and beta blockers is somewhere between 20 and 50.

He was not diverting meds and will, almost certainly, be the subject of a future reflection.

Been reading and enjoying since you launched Adam, but "Like most complex phenomena, this can be reduced to a 2X2 table" convinced me to upgrade to paid :)

It sounds like you are trained in motivational interviewing. Your patients are lucky! You must take a lot of time with each patient, and I'm curious if you ever get in trouble for that. It seems like most visits are expected to be 15 minutes or less these days! If you have a fair number of patients like PP (older with multiple chronic conditions), it must take a lot of time because you also have to discuss the potential adverse events due to polypharmacy in older people (link #1). Maybe you can write an article on deprescribing and how those decisions are made. Also, you're right about the NNT having a cringe factor, and I prefer the ARR for reasons discussed in link #2. But I'd still love to have you as my PCP. I promise not to fall into Boxes B or C too often! :)

https://bmcgeriatr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12877-021-02183-0

https://discourse.datamethods.org/t/problems-with-nnt/195/4