Goodharts Law and Medical School Admissions

"When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure."

I reference Goodhart's law too often. My last reference on Sensible Medicine was just last week, when I wrote about how turning United States Preventive Services Task Force ratings into a necessity for insurance coverage corrupted the quality of USPSTF guidelines.

Medical school admissions officers once noted certain qualities – like participation in research or volunteerism – among their applicants. There were no studies that proved that these qualities, or measures, predicted success in medical school or guaranteed future quality as a physician (however that would be measured). Nonetheless, they were qualities that were valued in some applicants. Over time, however, these measures became targets. This evolution not only left the measures useless but also disrupted the lives of applicants, caused us to miss out on many young men and women with great promise, and made our medical school classes less diverse.

Back in 1989, when I applied to medical school, during a historic population trough1, the admission requirements were pretty straightforward: good grades at a reputable college or university, supportive letters of recommendation, and strong MCAT scores. You also had to make a reasonable argument about why you wanted to go to medical school in a personal statement and interviews.

These relatively simple requirements served to demonstrate that you had done well at what was expected of you as a college student. They attested to your ability to do the “school work” portion of medical school and gave some sense that you were a good fit for medicine and a specific medical school.

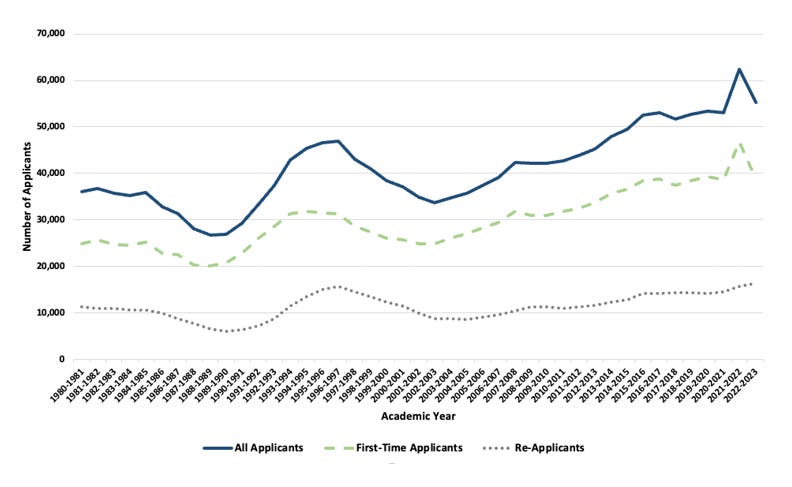

I can’t attest to cause and effect, but I can propose a story about what has happened since. The number of applications for medical school spots climbed. The time pressure on the doctors who work on admissions committees increased. It became necessary to find easier ways to screen applicants. Raising the grade and MCAT bar (and maybe the acceptable colleges, SATs, and APGAR scores) wouldn’t work as the bar was about as high as it could go, and, admirably, admissions committees recognized that there is more to being a doctor than the ability to ace a test.

A subset of students had always stood out because their unique life experiences and their “distance traveled” suggested resilience. Students destined to become physician scientists had done some research. Other students had demonstrated generosity and humanity through volunteer work. Some students could provide evidence of leadership or teamwork skills.

These measures, once present in a subset of students, became targets. Aspiring medical students shot at the targets and, because they were aspiring medical students, they did everything they could to hit them.

Grades and MCAT scores were targets when I applied, but hitting those targets just made you better at what you were supposed to be doing, excelling in your undergraduate education. The current targets are harmful to most students. Those uninterested in research sacrifice time during which they could be doing what they love to fill third-tier journals with drivel. Free clinics are filled with uninterested college students standing around, logging hours. Those lucky enough to have had an untroubled homelife argue that a bad orgo grade was a hill to climb.2

There is an argument that setting up these targets, or adopting them after students became convinced they existed, was beneficial. A student forced to do research might find that his calling is actually basic science rather than medicine. A student mandated to volunteer at a homeless shelter might find that doing the dirty work of doctoring is not actually for her.

I think that the harm of the current targets is greater than the benefit. We should trust our future doctor to make the right decision about their chosen career. We should let them develop themselves in the way that is right for them. We should then judge them for the diverse promise they bring to our field. Despite our professed attraction to those who have traveled great distances, we lengthen the distance by adding miles that only the most well-heeled can travel — extra years of low-paid work or experiences that interfere with paid jobs.

We profess to value diversity among our students, yet our admission requirements enforce homogeneity. If everyone must excel academically, publish articles, and complete service activities, how much diversity is left? Does the art history major, who aced his required science courses and then spent two years on a scaffolding restoring frescoes, fit into the current rubric? Is the English major, who waited tables to pay for a post-bac program, leaving no time for research or volunteer work, going to get an interview?

We’ve previously published pieces about more radical approaches to medical school admissions and curricular reform. Adjusting admissions targets is easier. Schools need to make it clear that they want students who have proven that they can do the work, learn the necessary material, and show promise for the wonderfully diverse field of medicine. This promise is best demonstrated by finding students who have identified what they love and then stood out doing it.

It will be more labor-intensive to judge students individually. This will demand investing in medical school admissions. Browse any major tech company website, and you will be horrified to see that coders are assessed more rigorously than applicants to medical school. All of us — students, teachers, patients — will benefit if we let students flourish, and then choose the best among them.

I do recognize that how absurd medical student family wealth is, at least seven years ago. I can’t seem to find more recent data.

Nice article, Adam, and I agree. What medical schools have done, unwittingly, is select for students (and later, practitioners) who are programmed to "play the game" rather than follow genuine conviction, in order to achieve short-term goal (admission, residency placement, job, salary etc.). This later follows in practice, and makes us vulnerable to administrators who exploit this goal-seeking characteristic -- defining success as a combination of meaningless metrics (wRVUs, volume, etc. etc.). Burnout ensues when the now mature physician realizes all that iterative short-term goal seeking had the long-term effect of trapping them on the low end of a bureaucratic hierarchy that views physicians as a commodity.

Strongly agree with this article. My entering class of 1983 included RNs, engineering grads w/a few years of work, parents, a mom who’d been on welfare (and became a splendid ObGyn), a former Navy medic, and at least one kid w/an economics degree who’d worked in a clothing store before his first year. People who’d had some experience with actual life. We were fortunate before my time, when soldiers returned from WW2 and went to medical school. Real people with REAL life experience.

Now? New physicians are striking for their monotony. It’s like the Big Room scene, from I,Robot. Well educated, but see how many can empathize with a truck driver and wife who live in a mobile home. Or a single mom who can’t undergo serial tests, because she misses work for each one. Or a veteran. Witnessing the disconnect on the inpatient OR outpatient setting is heartbreaking. Such people don’t exist in the upper middle class bedroom communities from which most med students arise.

I have no good answer. Only regret for the loss.