Highs and Lows

With a Comment on Involuntary Psychiatric Treatment

The names and various details of the patients presented below have been altered to preserve confidentiality. Permission was obtained for all images used. Some images have been altered to remove any identifying marks and preserve anonymity.

Luciana

Luciana’s discharge day was getting close. Her outpatient follow-up appointments were scheduled; we had reviewed her safety plan; she felt well and ready to leave the hospital. A few logistical wrinkles to iron out—most importantly the fact that she was now homeless—and she’d be on her way. She had been admitted for worsening suicidal behavior, which was a recurring problem for her, along with her tendency toward wild and rapid swings of mood, reckless impulsivity, and overall difficulty getting along with people. Barely thirty years old, and she had just burned her last bridge and had nowhere to go.

She had diagnosed herself as a “high-functioning borderline”, which I told her I thought was quite possible. Her hospital course was uneventful, and she made good therapeutic use of her time on the unit.

I came to her room for rounds in the morning. Her door was open, and she waved me in. I waved back, and as I made my way into her room to sit, I glanced down at the papers strewn over her hospital bed.

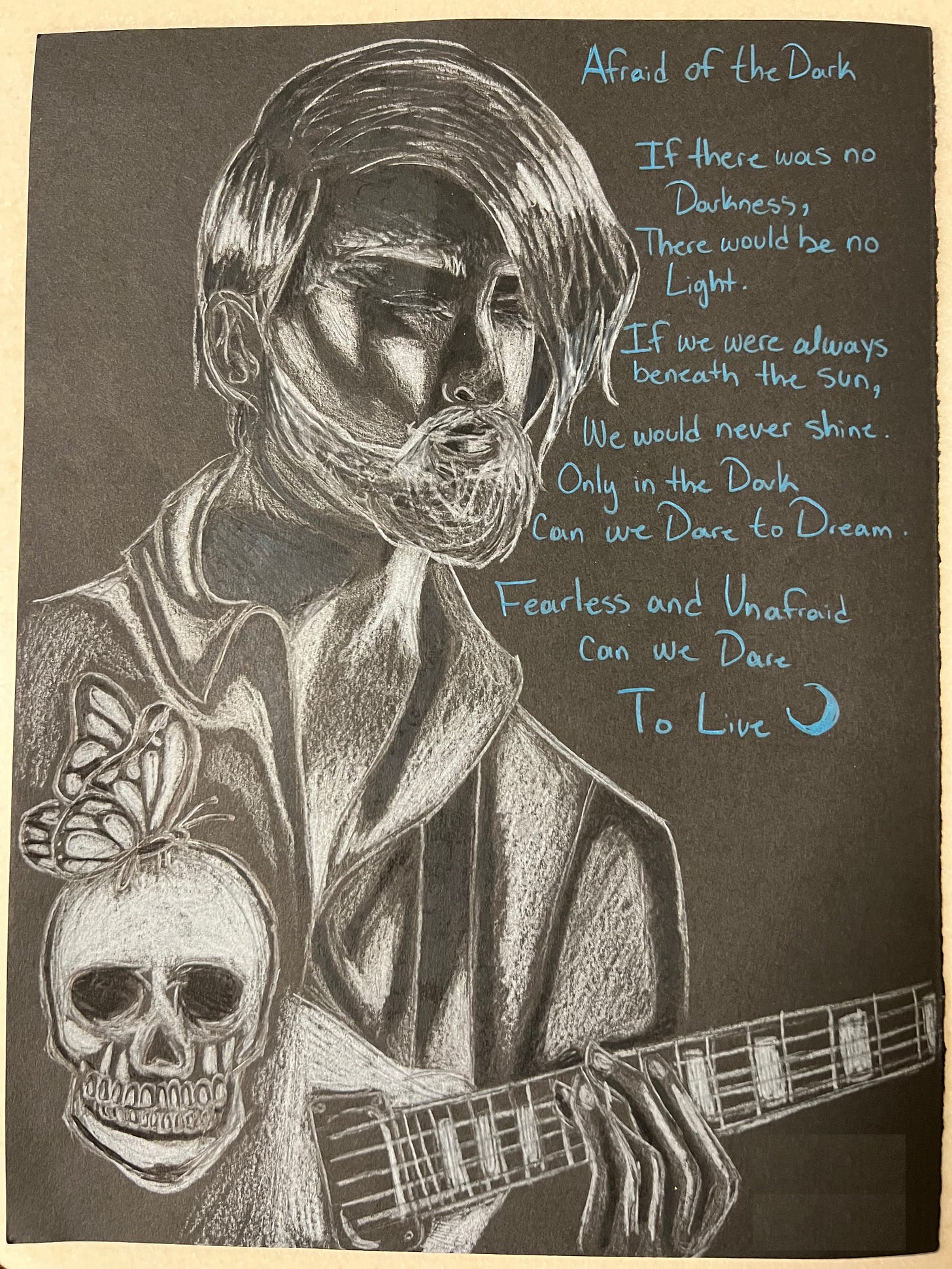

“Wow,” I said, “that’s really good. You drew that?”

“Yeah,” she replied sheepishly.

“Seriously, these are lovely,” I said, looking at the other drawings and sketches lying about. “Did you take drawing classes in college?”

“Thanks. I took one class a few years ago but otherwise no. I was thinking of getting back into it, maybe applying to art school, or being an art teacher for kids, or art therapy, or something like that.” She trailed off, sounding uncertain.

“Is the drawing therapeutic for you?” I asked.

She nodded, pulling a chair next to the bed and sitting down.

“Tell me about it,” I said as I squatted down next to the bed, resting one arm on the mattress to balance myself.

Each of her drawings, she explained, was of another patient she had met during one of her many hospitalizations. She typically gifted them to those she drew, keeping sketches for herself to refine later. The guitarist was a man who had nearly died by hanging but had found his salvation in music.

“I like giving them as gifts and making people feel good, yeah, but it also feels like when I’m drawing them, I can tap into their strength. Not like in some weird voodoo kind of way, just that I can remind myself of what they’ve been through, and that I can work through my shit too. Oh, sorry for cursing.”

“It’s ok,” I waived it off, “we all find our own ways to work through our shit.”

“True,” she chuckled.

“What do you think you worked through while you’ve been here?” I asked.

“In one group we talked a lot about shame”, she said, looking down at her anxiously tapping feet, “and for some reason it really hit me this time. I realized I feel shame all the time now. When I was younger, I think I was more angry, now I just feel shame.”

“Do you think about the shame when you’re drawing?” I asked.

“No, I don’t,” she said. “That’s another great thing about making art, you know, you don’t think about yourself as much when you’re doing it. Or at least I don’t. I just feel, I don’t know, peaceful, lighter.”

A knock at her door. A tech peaked in. “Breakfast is here, may I come in?”

Seizing the interruption before I turned this into a full-blown therapy session, I got up and brought the tray over to her desk.

“Thanks,” she said, sitting down to eat.

I segued the conversation to finalizing details on her medications and trying to figure out a place for her a place to stay, as the shelters were full.

“I’ll make some more calls after breakfast. Worse comes to worst, I can live out of my car. I still have a job, anyway, so I can save up money to get my own place,” she said between bites.

“Yeah, ok, but I’d prefer you not have to resort to that, so we’ll keep looking on our end too and let you know what we can find.”

As the conversation wrapped up, I started putting the papers back on her bed.

“Was this a draft of the finished one?” I asked, holding out a sketch.

“No, I’m doing another one. Different style, I think. The first one’s okay but it isn’t as good as I wanted it.”

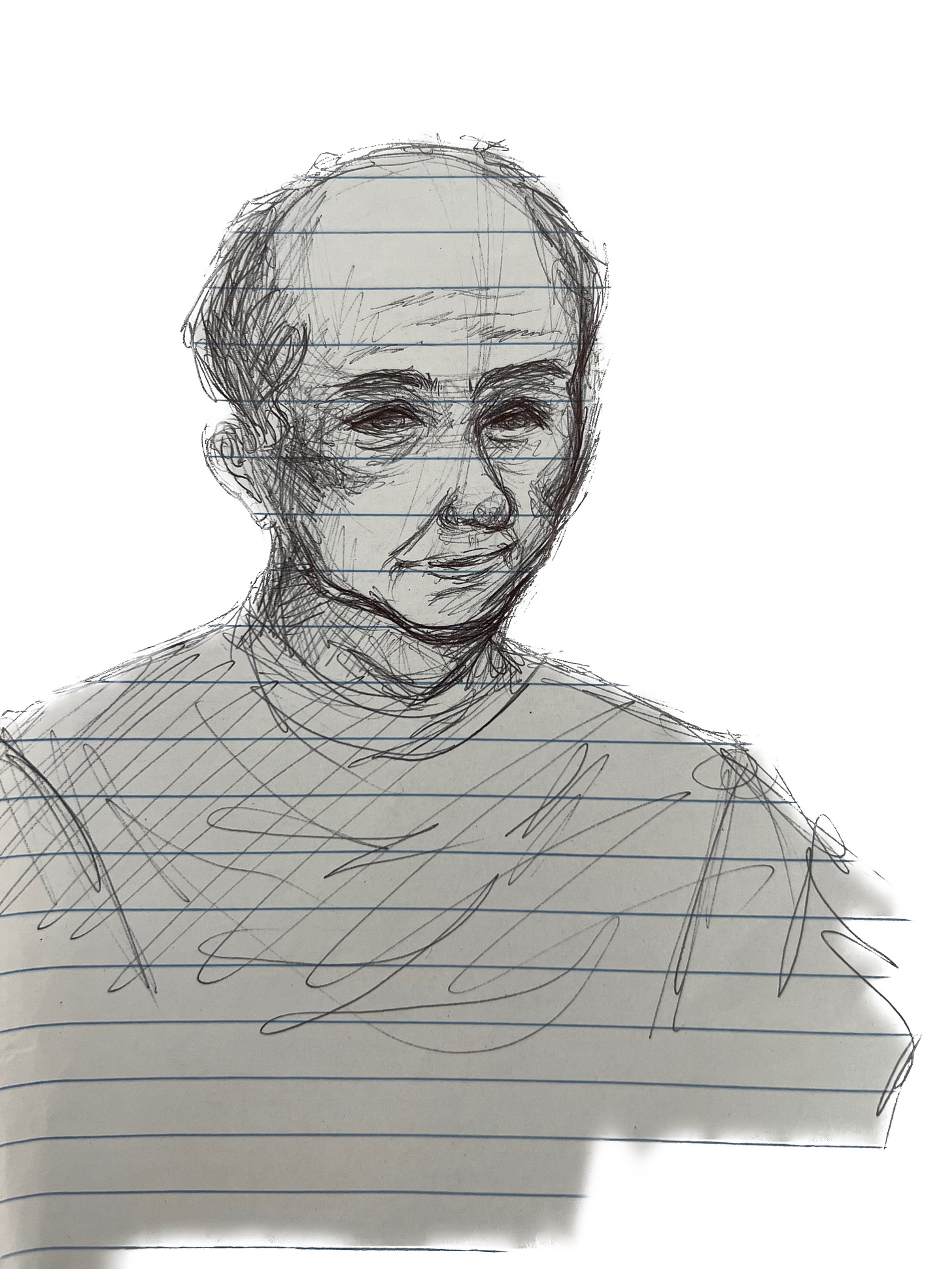

“Seriously? Well, for what it’s worth, I think it’s excellent. What about this one? I like his slight smile.” I handed her a page torn from a spiral notebook.

She said that during one therapy group she found particularly boring, she started a sketch of a man she had met years ago during one of her first hospitalizations. He was her grandfather’s age, admitted because his dementia had progressed to the point that he would physically lash out at his family and caretakers.

“But he was always nice to me,” she said, setting the page down.

We perused through a few more before coming to one that caught my eye. I picked it up. “That’s the most recent,” she said, “I’m making it for Sandra. She said she wanted a drawing of her and her nephew. I’ll have it done by the time I discharge.”

“That’s really lovely. I’m sure she’ll love it,” I said, setting it down gently and heading for the door. “Anyway, thank you again for showing me these. I’ll be back this afternoon and we can pick up the conversation then.”

Sandra

I would be seeing Sandra a few rooms over later that morning—and she had just started talking again. Sandra had been admitted weeks before Luciana and would not be discharged for a few more weeks to come. She had been brought to our hospital from jail, where she had been taken for some misdemeanor. At her scheduled release time, she was found sitting on the floor of her cell, rocking back and forth, appearing terrified and either unable or unwilling to speak. At times she appeared to respond to non-existent entities in the room. The report given to our ER noted she had smeared her clothes with her own menstrual blood.

In the hospital, she refused to leave her room or engage with staff. The only exception was the occasional few words to ask for food. She spent most of the day lying in bed or pacing her room. We had little information about her: she had no prior history in our medical record and was not in possession of identification. The police suspected she was from out of state but couldn’t be sure. And she wasn’t telling us anything. When we came to see her each day, she would retreat into the bathroom. Despite repeated pleading, she would not take any medication. We were at an impasse.

“We have to take her to court,” her social worker said after rounds. “Nothing is working, and she’s really sick.” I agreed.

Sandra had been petitioned and certified for involuntary psychiatric admission when she arrived, which basically means that, if she wants to leave, we can keep her for about a week for emergency stabilization, at which point we can either go to court, or release her.[1] If we go to court, that means we petition the state to allow us to (a) keep her in our hospital for up to 90 days and (b) treat her against her will. The proposed treatments are selected by the attending psychiatrist, and typically consist of a variety of psychiatric medications likely to be helpful for the patient’s condition, as well as any monitoring tests necessary for their safe administration (bloodwork, EKG, etc.). In addition, we frequently petition for electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), one of psychiatry’s most effective and often life-saving procedures. Each treatment, test, and procedure need to be specified carefully and justified to the court, as we are not granted license to do whatever we want. Eventually, I am sworn in before the judge and answer various questions from lawyers, while trying to justify why I think she needs to be compelled into treatment.

A lot has been written lately about the need for, and workings of, involuntary psychiatric treatment, and I won’t review it all here. Much of it is useful and insightful, while some verges on the panicked and paranoid. One thing I do want to stress, however, given the often-confused public perception of the process, as well as a vocal minority who seem to think psychiatrists revel in strapping down protesting patients and jabbing them with who knows what scary drugs, is that involuntarily treating patients is almost always a huge pain in the ass. The resource strains, time constraints, and lack of staff on both the hospital and legal side can make meaningful involuntary treatment impossible in some places. Even in my fortunate case, in a well-run hospital with highly competent staff who have a long working relationship with the local court system, the hours it takes one or two social workers and me to get through the whole thing can slow down an entire hospital unit for over a week.

Additionally, staff tend not to like treating patients against their will. Most patients on most psychiatric units sign in voluntarily, even when psychotic. Patients who really don’t want to be hospitalized can cause major disruptions on a unit and suck up a lot of staff time. Contrary to the fear held by some that we try to cook up reasons to lock people in padded rooms, much of the discussion on morning rounds centers on the question “what needs to be accomplished so that we can get this patient discharged as soon as is safely possible?”

Personally, treating patients involuntarily is difficult. It can wear on you. Even when I am as certain as can be that we are saving someone’s life, and that I will be vindicated once they’ve recovered, it is never easy telling someone that they are sick and that you are going to treat them against their current wishes. I have pretty thick skin, and I’m drawn to the extremes in humanity. I tend to work well with adversarial, hostile, manipulative, and agitated patients. As used to it all as I am, though, the thought of being robbed not only of my faculties, but of the ability to even know that I am sick and need help, is truly terrifying. Perhaps this speaks to one reason we are under-treating the sickest among us—that for many it is simply too painful to watch, much less acknowledge.

Luckily for us, “taking her to court” meant that the judge and lawyers would come to our psychiatric unit and hold the legal proceedings in our rec room, sparing us a trip to the courthouse. We struggled to pull the chairs around the table, as they were weighted to prevent a patient from throwing them through the windows.

The proceedings went as expected. Sandra would not even speak to her public defender or appear before the judge to speak for herself. It seemed that, despite our repeated discussions, she didn’t quite understand that a legal proceeding was even underway (here it is worth mentioning that the bar for involuntary treatment is quite high. If a patient gets before the judge and is reasonably cogent, we are quite likely to be denied our petition). I testified that, based on my evaluation of her history and current presentation, as well as the corroborating observations of numerous colleagues, Sandra was impaired to the point that she could not care for her basic needs and was unable to protect herself from serious harm without assistance. Her impairment was caused by a psychiatric syndrome called psychosis (in her case due to schizophrenia), and that it could not be treated without medication. The benefits of forcibly hospitalizing and treating her, I argued, unquestionably outweighed both the risks of treatment and the temporary infringement on her liberty.

Here there arises one of the fundamental objections to involuntary psychiatric treatment, namely that it violates the liberty of the patient. There is truth to this, of course. At the same time, we must acknowledge that wandering around the streets psychotic, at risk of predation from others and possibly dangerous to yourself, is a shallow kind of liberty indeed. Attempts to normalize and romanticize mental illness are gravely mistaken, and typically end up hurting the sickest among us. The reality is that severe mental illness is a curse, as anyone who has experienced it or seen it up close understands. Few other illnesses so devastatingly impair our perceptions, judgment, ability to exercise choice, capacity for fulfilling relationships, and even our basic sense of self. Withholding treatments, even our decidedly imperfect ones, is just cruel.

The court granted our petition, and we began treatment with antipsychotic medications. Progress was slow going initially, but gradually over the weeks she started coming to life. She spoke, if only briefly at first. Then she started bathing herself. I knew we were making strides when she gave me a snarky complaint about the hospital food. It was a long time before she could talk to us for more than a few minutes before putting her head under the blankets and shutting down.

Eventually, she started telling us about herself, filling in the gaps of her past. Her schizophrenia had emerged later in life, a few years prior to our meeting. Before that, she said, she had devoted her life to raising her nephew from a young age.

“How are you feeling this morning, Sandra?” I asked as I walked into her room. For the last few days, she had been looking better, and she had started wearing clothes instead of hospital gowns.

“Highs and lows,” she replied. She was sitting at her desk, looking at a photograph. I walked over to her and saw tears in her eyes. She pointed to the photo. “That’s him.” Sandra’s brother, whom we had finally been able to contact, sent us photos of her and her nephew, who she had raised like a son, to put in her hospital room. The photo Sandra was holding, which Luciana would later use to for her portrait, was taken just before her nephew enlisted in the military.

“I raised him good. I saved my money and sent him to the one good school in our town. Graduated top of his class, you know?” It had been years since she last saw him. We weren’t even sure when she had last seen a photograph of him.

“Do you want to try calling him today?” I asked. We had been encouraging her to call for days, but she insisted she couldn’t. In her paranoia, she believed the phones had been disconnected, or (somehow or other) their communication was being blocked.

She paused and thought about it. “Maybe I could try today.”

Luciana

I returned later that day to find Luciana at her desk, hunched over a book. She looked up at me as I walked in.

“What are you reading?” I asked.

“It’s a book on sketch art.” She held it up for me to see. “I’ve been trying to draw more fantasy and horror stuff. But also cute and goofy things, more like comics or ghost stories for kids.”

“I definitely want to see whatever you’ve been working on, but first, any luck on finding a place to stay?”

“Yes, actually!” She got up excited, “one of my friends who hadn’t picked up when I called the first time just got back to me. She said I could stay with her for a few weeks until I figure things out.”

“Wonderful, we’ll coordinate transportation and plan for discharge tomorrow morning.”

I took one last look at her work as I turned to walk out the room. I picked up a sheet on her desk filled with small doodles. “What’s this one?” I asked.

“Oh this? It’s my self-portrait,” she said, smiling.

[1] The legal details of involuntary psychiatric admission and treatment vary from state to state. I am aware of no state in which involuntary admission is granted solely on the basis of having a mental illness. Typically, criteria such as being an imminent threat to self or others, inability to care for oneself, or risk of imminent clinical deterioration must be met. There are other differences: who can initiate the petition process (in many states any adult can initiate a petition, but some restrict it to family, law enforcement, physicians, or other specified parties), who can perform the relevant psychiatric evaluation, duration of treatment, whether someone can be committed for alcoholism or drug abuse, and various legal technicalities.

Dr. Greenwald is a psychiatrist practicing in the midwestern United States. He is on Substack at Socratic Psychiatrist.

Interesting and thought provoking when you realize how devastating mental illness can be.

Thanks for your compassion as you deal with these real people who have real lives.

My psych rotation was in a "State Hospital". A ward/floor for different diagnoses. I was terrified at my first visit. It was dreary, loud, chaotic, random. But, as I settled in and learned more in my class time which I took with me to 'my ward' I realized the need of such a facility, the treatment and watchful eye caring for each individual.

(After graduating I worked on a locked unit which was also a voluntary unit - [yeah I know]) This was a wing attached to a hospital. 4 floors treating different diagnoses. It seemed futile as I thought it too little, too late.

I watched the State Hospitals drop off the skyline one by one like trees being cut down for growth and modernization. I don't know why they aren't around any longer. Yes, they needed a face lift, more funds to run, experienced staff, etc., but they kept people safe, off the street where it is so dangerous. Patients had instant access to a meeting, group, medication. I'm only 1 little person knowing this much [ ] about something so vast.