How JAMA Psychiatry Fooled Us About Antidepressant Withdrawal

Will Ward disagrees with my assessment of a JAMA-Psychiatry meta-analysis. His argument is persuasive and belongs on Sensible Medicine JMM

Dr. Mandrola recently highlighted JAMA Psychiatry’s antidepressant discontinuation meta-analysis by Kalfas et al. It concludes that antidepressant discontinuation causes symptoms “below the threshold for clinically significant discontinuation syndrome.”

The authors suggested placebo-controlled RCTs do not support the existence of severe or protracted withdrawal. To some, these results were surprising. Could it be that antidepressant withdrawal1 (aka discontinuation syndrome) is always mild and brief? Perhaps “severe” withdrawal is just a nocebo effect.

The meta-analysis certainly appeared to be well done. The methods seemed robust. A neutral alien reading the paper would conclude the positive findings were backed by strong science.

Yet, many who have taken antidepressants for extended periods of time find the paper’s conclusions difficult to believe. Rather than mild and brief, critics suggest withdrawal is debilitating.

Could they be right?

To answer this question we must look through the supplementary materials. This is where the limitations can be seen.

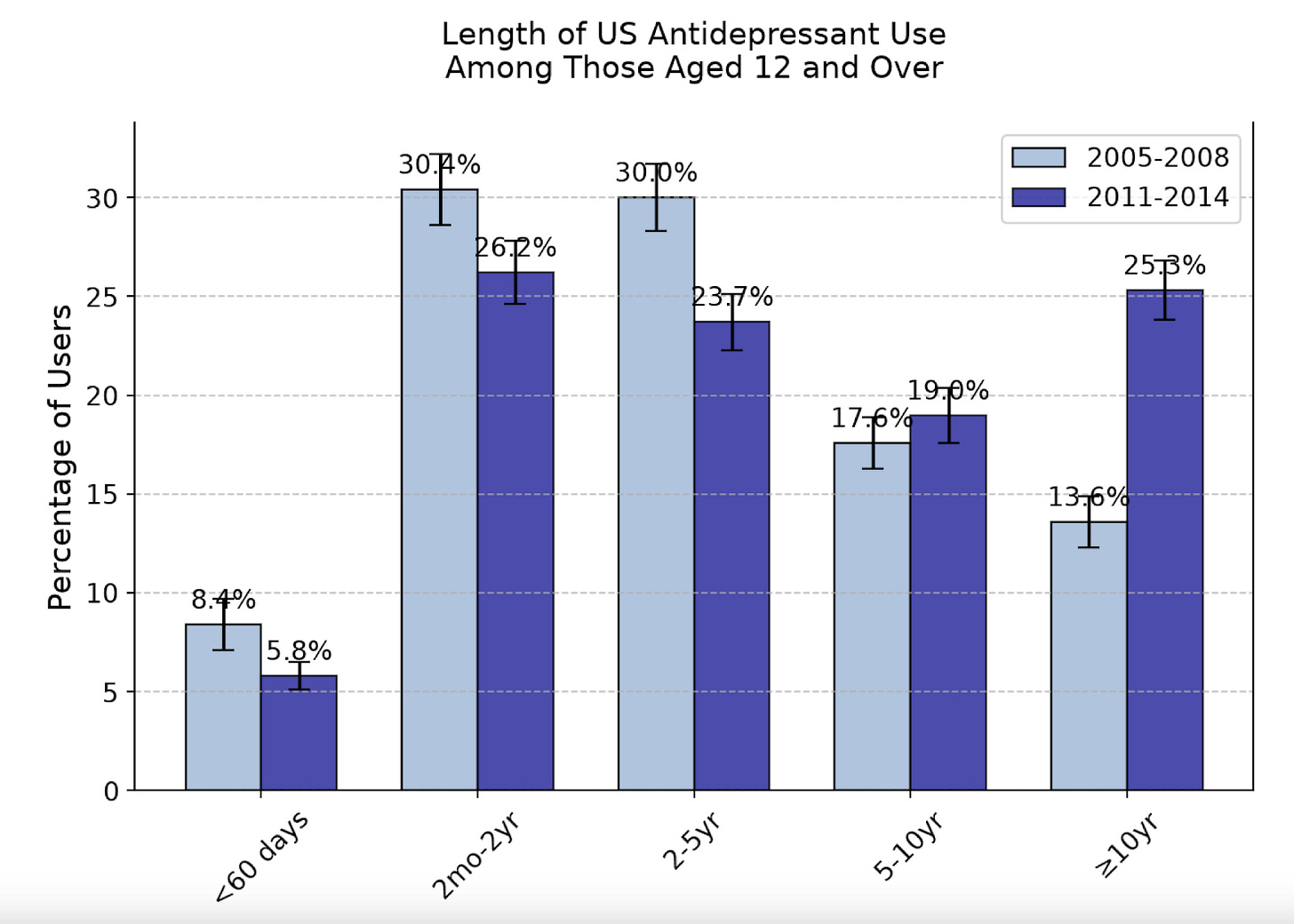

Duration of use

A few months ago, a paper I wrote with Dr. Prasad was featured as Study of the Week.2 We highlighted an unsettling problem: nearly 90% of placebo-controlled antidepressant RCTs assessed efficacy over 12 weeks or less. Long-term trials are scant and tend to report atypical outcomes. Yet half of those taking antidepressants have done so for more than 5 years. This group represents many millions of people. According to CDC data, the duration of use was rising 10 years ago.

The disparity between the studied and practiced duration of antidepressant use is problematic. There are valid concerns that the risk, duration, and severity of antidepressant withdrawal grow with prolonged use. But this problem is not well captured in acute antidepressant use trials.

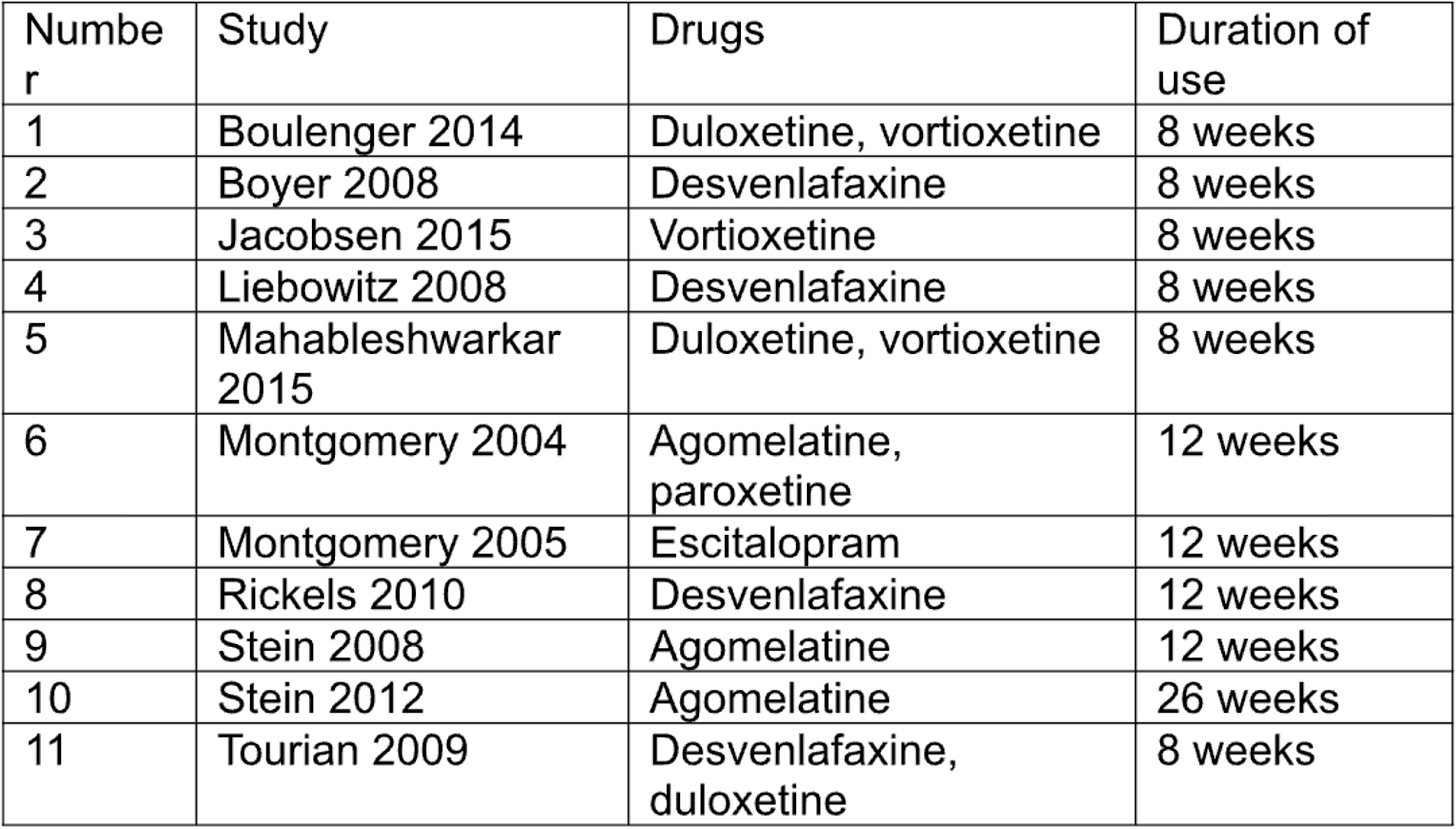

The JAMA meta-analysis included 49 studies, some of which discontinue antidepressants after “36 weeks to 4.5 years” of use. Only 11 RCTs that report Discontinuation-Emergent Signs and Symptoms (DESS) were used for the central statistical analysis. Only in the supplementary materials is the duration of antidepressant use in these trials revealed.

Mark Horowitz produced the table3 that should be front and center:

Ten of the eleven trials discontinue antidepressants after ≤12 weeks. There is a 26-week outlier. But this trial involves agomelatine, which is not known to cause withdrawal and is not approved in the United States.

I believe the reason why the authors found “no association between anti-depressant treatment duration and discontinuation symptoms” is the short duration and narrow outcome window. And if this is true, the authors’ meta-regression was flawed and unable to sort out a signal of time of therapy and symptoms of withdrawal.

Contradictory Evidence

Because many depression and anxiety symptoms appear on DESS, those withdrawing from antidepressants are easily misdiagnosed with a mood disorder.

For this reason, trials that follow mental health outcomes upon antidepressant discontinuation can incorrectly characterize withdrawal as relapsed mental illness. Despite this shortcoming, “relapse prevention” trials contain compelling evidence that clinically significant withdrawal does exist.

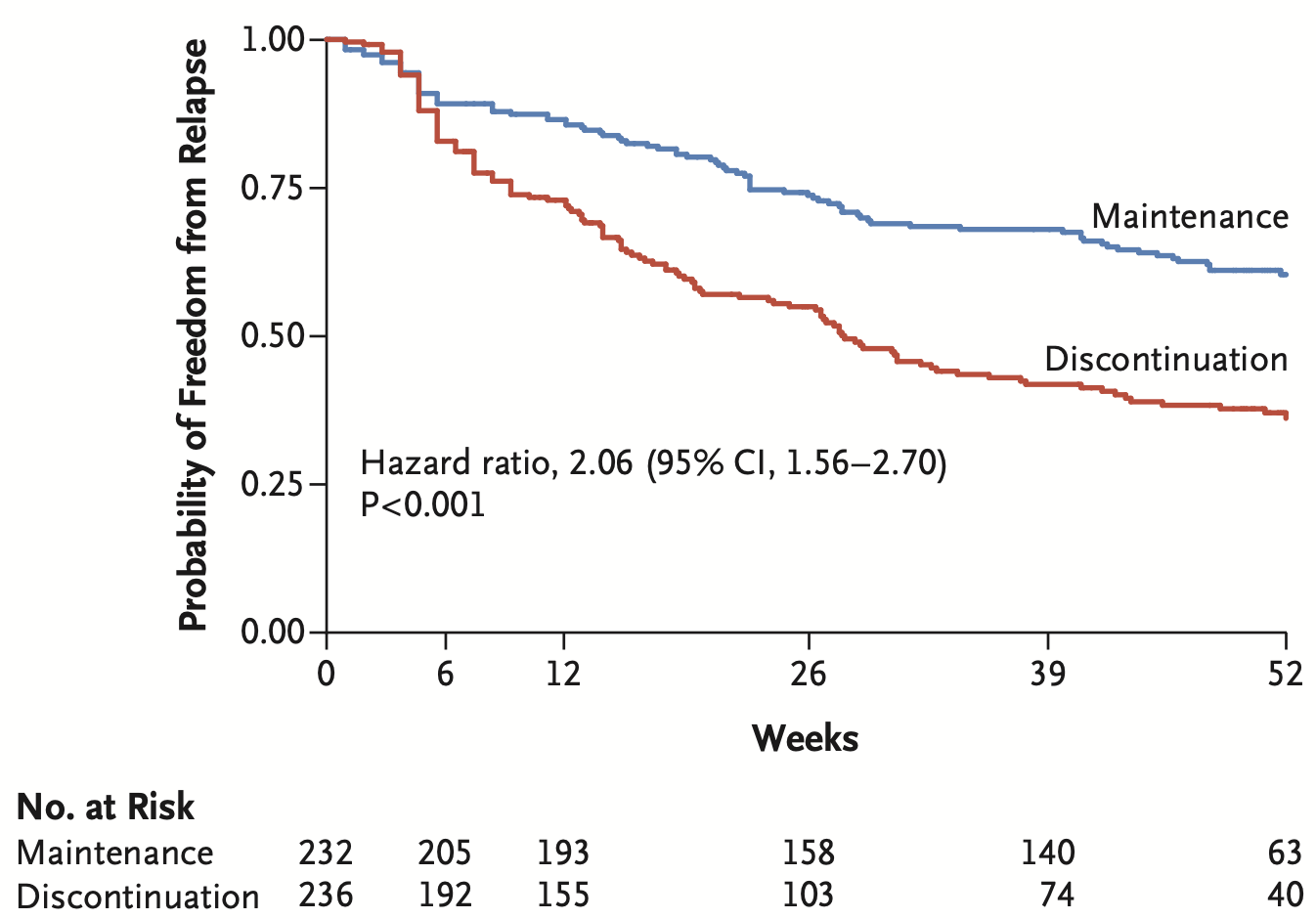

The ANTLER trial is mentioned in the discussion section, but is excluded from the paper’s DESS analysis. This trial randomized well individuals on antidepressants for 2+ years to either taper or continue treatment. At 12-week follow-up (4-8 weeks after discontinuing antidepressants), DESS scores were markedly elevated in the discontinuation arm. The standard mean difference (SMD) was 1.0 for sertraline, 0.52 for citalopram, and 0.50 for fluoxetine.4 These scores are higher than the SMD produced by the meta-analysis (0.31). For reference, SMDs of 0.2 and 0.8 are respectively considered small and large effect sizes.

Kalfas et al claim that ANTLER's elevated DESS scores are caused by relapse, not withdrawal, because the elevations appear at extended follow-up. The meta-analysis only includes DESS scores reported one to two weeks following discontinuation, so ANTLER's findings were excluded.

ANTLER's Kaplan Meier curve suggests something more than “relapse” may be occurring.

Why do the curves separate rapidly after 4 weeks? After a brief taper, antidepressants were entirely discontinued between weeks 4 and 8. The curves separate precisely where withdrawal symptoms might appear.

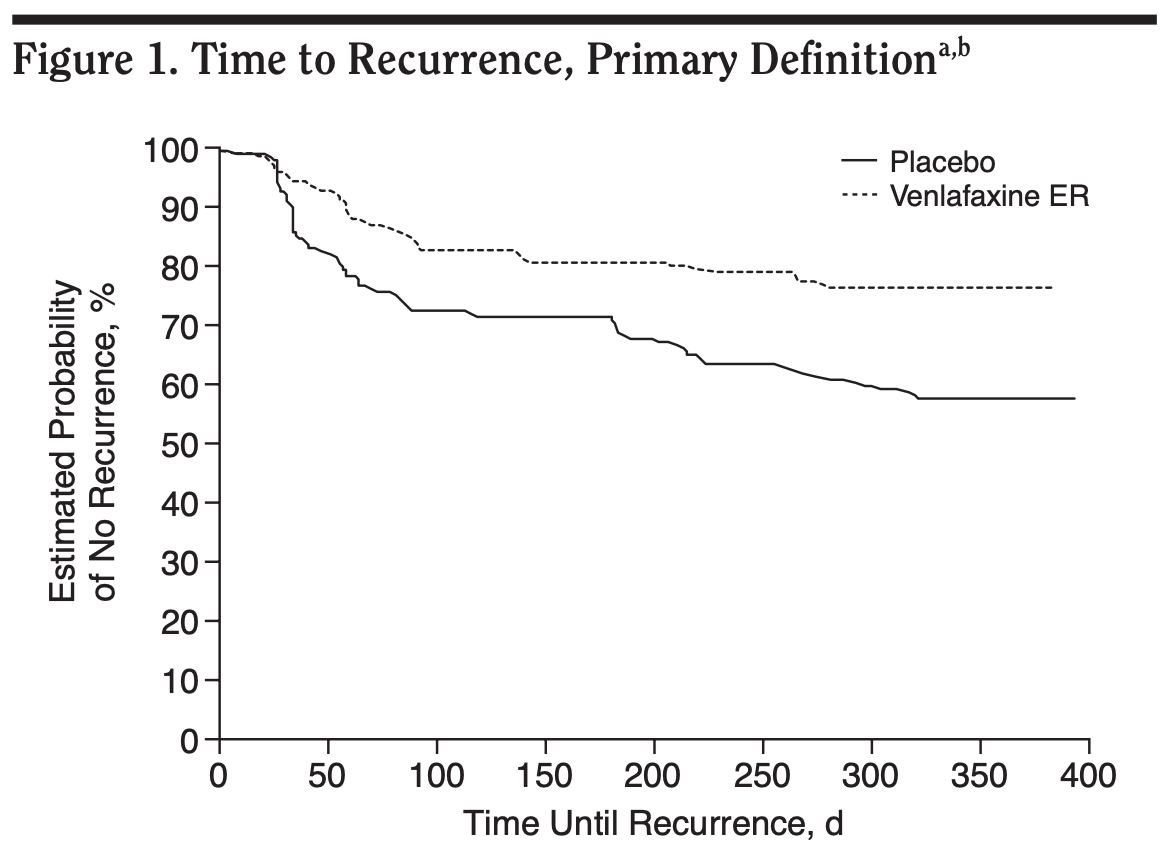

Variations of this Kaplan Meier curve appear across the “relapse prevention” literature. The American Psychiatry Association last recommended long-term prescribing based on the PREVENT study, which did not report DESS or any other withdrawal outcome. The trial randomized healthy patients to either taper or continue venlafaxine after 34 weeks of treatment. “Relapse” rates were 44% and 8%, in the respective trial arms. This effect size is surprisingly large, considering initiation trials have not found antidepressants to improve remission rates after 6 months of treatment. We again see rapid curve separation following completion of the 4-week taper kit, suggesting withdrawal occurred.

Fallout and Opportunities

It is disappointing that Kalfas et al did not quantify the most relevant trial characteristics in the paper. By failing to do so, they misguide physicians hoping to properly inform patients about antidepressants. This paper also guarantees divisive discourse surrounding the topic. It is a shame this meta-analysis passed peer review. Considering their framing is misleading, I believe the authors should issue a correction.

Most frustrating is that this is a topic of high importance. A large number of people have taken antidepressants for more than a decade, many of whom will experience withdrawal. Yet, symptoms often go unrecognized by psychiatrists and general practitioners expecting withdrawal to be brief and mild.

I recently met a patient who has taken duloxetine for 18 years. Like clockwork, she experiences nausea, dizziness and intense anxiety exactly 4 days after her prescription runs out. The symptoms are debilitating and prolonged, yet quickly resolve upon restarting medication.

Before I met her, she had never discussed antidepressant withdrawal with a doctor. Yet, she knew her symptoms were caused by medication discontinuation.

As suggested in the Maudsley Deprescribing Guidelines, I believe patients are showing withdrawal effects when these features are present:

Symptoms are incongruent with the original mood disorder. There may be new nausea, dizziness, or brain zaps. Perhaps psychological distress takes on a new quality or intensity never experienced before.

Onset of symptoms is days to weeks after medication discontinuation.

Symptoms quickly resolve after medication resumption, much faster than is expected from initial antidepressant treatment

In the past few years, I’ve met several dozen individuals who meet these criteria. I worry there may be millions of unrecognized cases.

We cannot improve patient care until we acknowledge the discordance between antidepressant research and real-world use. A severely restricted evidence-base cannot produce sound conclusions; it risks overlooking harm.

Footnotes

I use “withdrawal” interchangeably with “discontinuation syndrome”. The word “withdrawal” is more widely understood, so I prefer to use it.

This was a highlight of my career so far. Thank you.

Thank you Mark Horowitz for providing this updated table and commenting on an earlier version of this piece

These numbers are not found in the meta-analysis itself, rather, in eAppendix 5. Standard mean difference = The difference between the means of two groups / pooled standard deviation. An SMD of 1 indicates the means are different by 1 standard deviation.

This is exactly the problem. The science only covers a very short time and these drugs are used for much longer. I too think antidepressant withdrawal is often mistaken for relapse. I can see the faces of my own patients who educated me and informed my own practice in the early ‘90s before medical literature contained anything useful on this subject. This withdrawal is certainly distressing to those afflicted. While not as intense as opiate or amphetamine withdrawal it’s real danger is that it will be mistaken for the original disorder for which it was prescribed. In this catch-22 the drugs might be continued ad infinitum.

Just one more observation. Meta-analysis is not science as this author states. It is a statistical stratagem that can be useful to indicate areas that need actual scientific activity but in and of itself it should not be given settled science status.

Dr. Mandrola, I'm a frequent reader of Sensible Medicine, but I still find it fascinating that you are ready to publish articles that dispute your own writing. I know, it should be standard, but we are far away from standard recently. Disagreements are mostly published as a fierce rebuttal, with personal attacks and language that guarantees very strong language back. Or not published at all. Disagreements published here make me believe that science can still work as it's supposed to. Through politely formulated objections, questioning, and proposals for amendments. Thank you for that.