Is Anticoagulation (actually) More Dangerous than Low-Dose Aspirin

The Study of the Week reviews a sub-analysis of the recent ARTESIA trial of apixaban vs aspirin in low-burden AF. The findings relate to left atrial appendage closure

One of my longstanding arguments against left atrial appendage closure for stroke prevention is that patients with the device still take aspirin in the long-term. One school of thought is that aspirin in much safer (less bleeding) than oral anticoagulation (OAC).

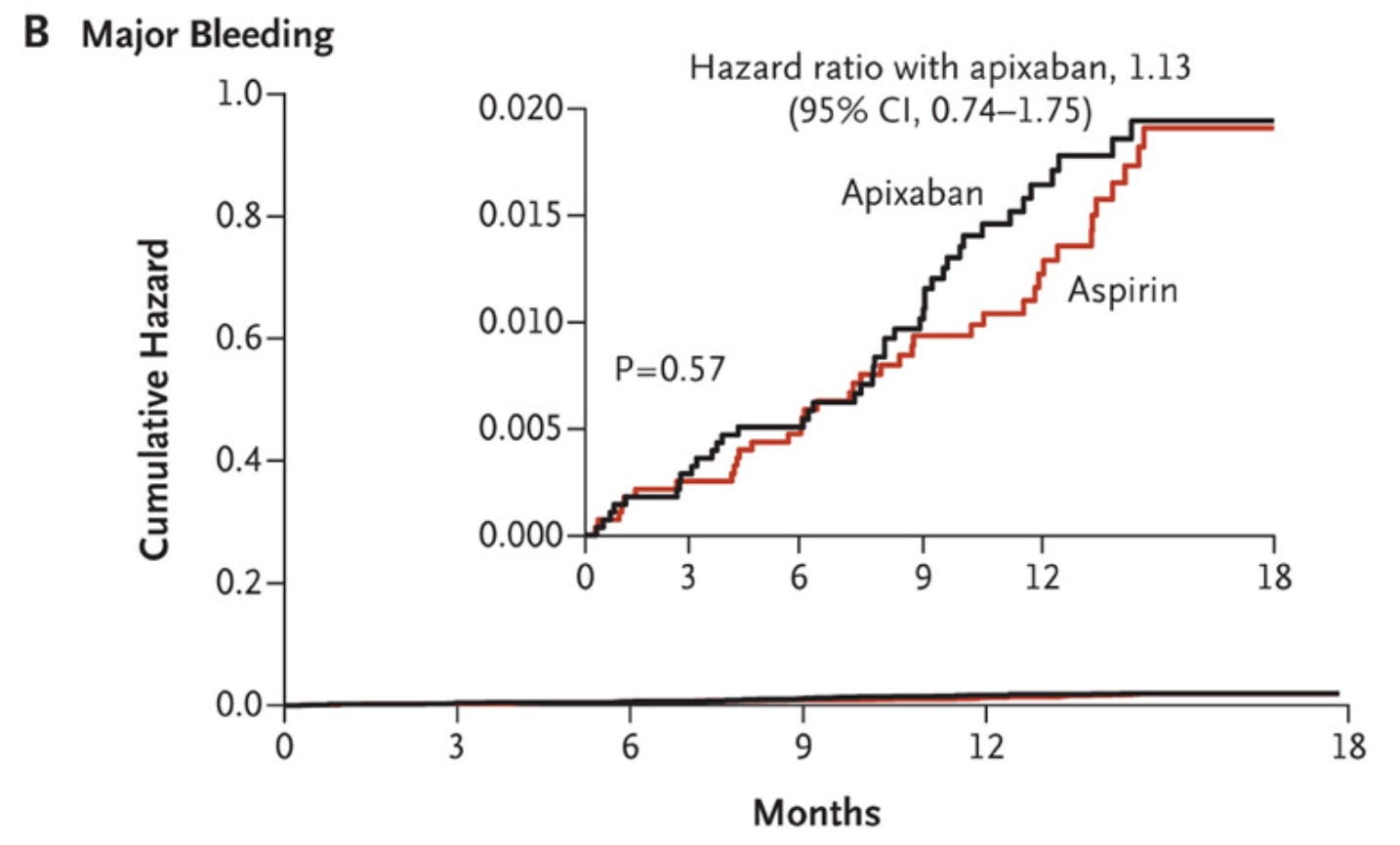

But the 2011 AVERROES trial where the anticoagulant apixaban was compared to low-dose aspirin for patients with AF who were unsuitable for warfarin. The graph below shows that that major bleeding rates were similar.

Purists will say, John, in the as-treated analysis of AVERROES, the rates were 1.4% vs 0.9% and the HR was 1.54. But still the 95% confidence intervals were 0.96-2.45, so it did not reach significance.

My points were that a) apixaban is a quite safe OAC, and b) aspirin is not as safe as people think. In other words: taking low-dose aspirin is not nothing.

ARTESIA Substudy Results

The ARTESIA trial compared apixaban to aspirin in patients with “subclinical” AF detected from a cardiac device. The average duration of AF episodes was short at 1.5 hours.

The main results of ARTESIA was that apixaban was associated with a statistically significant 37% lower rate of stroke or systemic embolism. The absolute risk reduction was tiny at ≈ 0.5% per year.

The main safety endpoint in ARTESIA was bleeding in the on-treatment arm. It was 80% higher in the apixaban arm. The HR of 1.80 had 95% confidence intervals of 1.26-2.57. But again, the absolute risk increase was small at ≈ 0.8% per year. There were 28 more bleeds in the apixaban arm in a trial of 4000 patients.

The recent paper, published in JAMA Cardiology, characterizes the bleeding episodes.

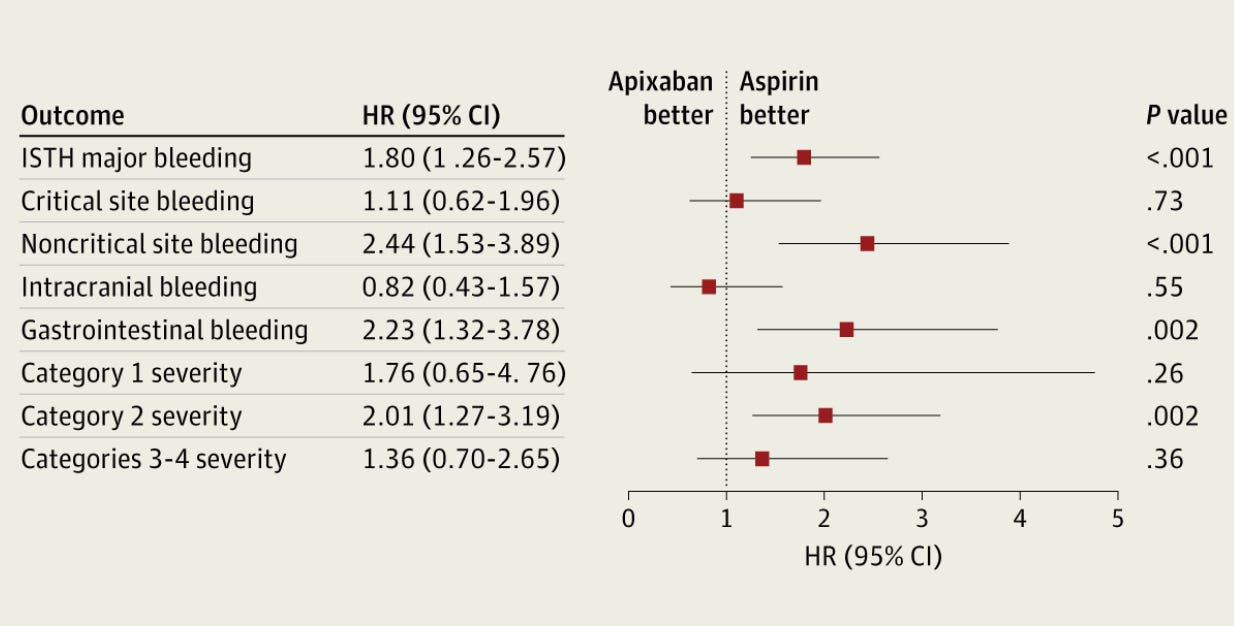

The picture shows the main findings.

For critical site bleeding (brain, eye, pericardium and joint) the rates were 25 and 22, respectively. So no different.

For noncritical sites, (GI, urine, bruising, surgical site, or nose bleeds) it was 62 vs 25 events, and that was statistically higher.

For fatal bleeding, it was 5 vs 8, so not significantly different and quite low.

For bleeding requiring transfusion, it was 28 vs 18, which did not reach statistical significance.

The researchers then broke down the severity of clinical presentation into four categories:

category 1 (not an emergency)

category 2 (not an emergency but need for some treatment)

category 3 (hemodynamic instability [low BP])

category 4 (death before or almost immediately after presentation)

Here, they found that the higher rates of bleeding were primarily in category 2 (54 vs 27 patients). There were little differences in very minor or very serious bleeds.

Other than randomization to apixaban, they also identified three other factors associated with higher rates of major bleeding: NSAID use (10x), cancer (3x) and age (1.47)

Comments

I see 3 useful take-homes from this contemporary comparison of bleeding rates with apixaban vs aspirin in older patients.

One is that apixaban is quite a safe anticoagulant. Rates of major bleeding was only 1.7% per 100 patient-years (which is roughly equivalent to 1.7% per year. And most of the bleeding that occurred was not critical site or fatal bleeding. Recall also that these were 77-year-old patients. The authors ask us to balance that harm against the 37% reduction in stroke in the trial. I think it’s a reasonable argument. Though patients will feel differently about the balance.

The second conclusion is that aspirin also causes major bleeding in older patients. The rate of major bleeding was slightly less than apixaban, but it approached 1% per year. And aspirin did not seem to protect patients from major or fatal bleeds. In fact, for intracranial bleeds (the most feared), rates of bleeding were actually numerically higher in the aspirin arm (20 vs 17). Same for fatal bleeds (8 aspirin vs 5 apixaban).

The lower rates of bleeding in ARTESIA with aspirin were driven by less serious bleeding. This is not nothing, but the most feared and scariest bleeds were not reduced by taking aspirin.

What I take from this is that the long-term use of aspirin in patients who have left atrial appendage closure is not as protective as proponents think.

This was confirmed in the most recent CLOSURE AF trial where bleeding rates were 7.4% in the LAAC arm vs 6.23% in the “best medical therapy” arm, which mostly included OAC.

Finally, the notion that aspirin is beneficial has not been born out in contemporary primary prevention trials of aspirin vs placebo. ASPREE, ARRIVE and ASCEND reported null results for net benefits and all found higher rates of major bleeding with aspirin. ASPREE recruited older patients and found a trend to higher mortality in the aspirin arm.

Taken together, we should no longer believe that low-dose aspirin is a safe drug to give to our older patients.

And the need for long-term aspirin in patients with left atrial appendage closure devices is clearly a negative drain on any purported net benefits.

John,

I have no dog in this hunt, as my patients are at the other end of life.

And I appreciate your reliance on the data you present. But…

How do you get from

“the long-term use of aspirin in patients who have left atrial appendage closure is not as protective as proponents think”

to

“we should no longer believe that low-dose aspirin is a safe drug to give to our older patients.”

Not safe seems a very harsh conclusion to draw from the data presented.

Sad that relative cost is not a consideration. Aspirin is dirt cheap and OAC I suspect is a lot more expensive what is the number of strokes prevented per dollar spent on therapy?