Netter vs. Sketchy

Working toward intergenerational communication and understanding

My routine when I attend on our inpatient general medicine service is to occasionally table round with the team, then see our patients with the 3rd-year medical students.1 This schedule enables me to complete my work while spending time teaching the students by demonstrating nuances of the physical examination and pimping them.2

Recently, on rounds, I started questioning the students on some inane point. I can’t remember the topic, but I am sure it was only peripherally related to patient care, and that mastering it would never benefit the students or their future patients. Each time a student answered a question, I came up with another, even more obscure and esoteric. I finally came upon a question that stumped them. They looked over my left shoulder, with strangely unfocused gazes. I turned, seeing nothing but a blank wall.

Me: “What are you thinking about?”

Medical Student #1: “I’m trying to picture the page from Sketchy.”

Medical Student #2: “That’s hilarious, I was doing the same thing.”

Me: “Sketchy?!?! “How can you admit that to me? You do know I wrote a textbook. Which, by the way, I hope you own and paid full price for.”3

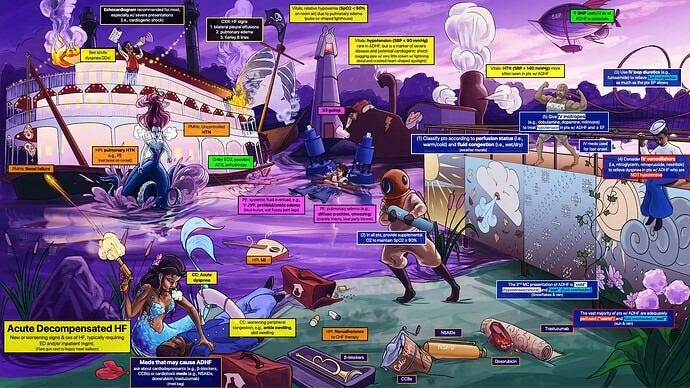

Sketchy is a site that many medical students love and many older medical educators love to hate. The site features detailed images to teach concepts. Their pitch is:

Learn and retain medical concepts faster with Sketchy’s signature visual lessons. We transform dense, overwhelming material into fun stories and quirky symbols that stick with you from classroom to clinic.

Here is a sample image, this one covering acute, decompensated heart failure.

A couple of weeks later, I was teaching in our Master of Science in Biomedical Science program. The course is called: Foundations of Clinical Medicine: Anatomy, Physiology, and Disease. This course covers much of the preclinical medical school curriculum in a single quarter. Teaching it is a treat as I get to revisit the anatomy and physiology of the human body. Not one lecture goes by that I don’t reflect, often out loud, “Our bodies are incredible, right?”

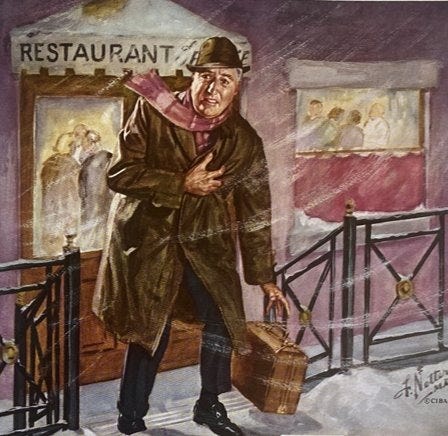

On this day, I was teaching about cardiac disease. I’d started with coronary artery disease, and one of my first slides about stable angina featured a painting by Frank Netter:

After giving my usual apologies — “I know Netter drawings are pretty dated. Pretty much everybody is white and middle class, and yes, I know that women can actually get coronary disease.” — I went on to sing the praises of this image:

This is a perfect picture of textbook angina. He’s a middle-aged guy, he probably just had a large meal, now he is climbing stairs, in the cold, and he clutches his left chest — maybe because of the pain or maybe he is looking for his bottle of nitro. Check out the special treat of the dropped briefcase.4

I include Netter images in a lot of these talks. The clinical images do a nice job of showing students what these diseases look like in people. There is no better way to learn than to link diseases to actual patients, but short of that, at least you can link them to a memorable image of a patient. I find the images to be remarkably sympathetic. Most of them are empathic rather than voyeuristic. I also have a warm place in my heart for Netter illustrations because a family friend gave me a collection of Netter books when I was first accepted into medical school.

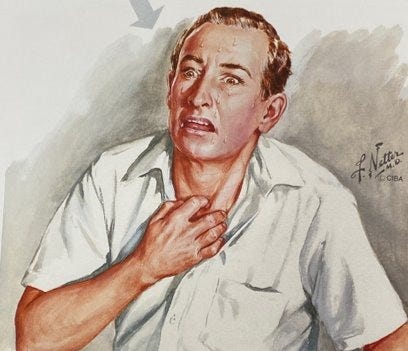

Another image that I use shows a man in the throes of an asthma exacerbation. The desperation in this man’s face is obvious. As someone who struggled with asthma as a kid, I can remember the constricted feeling that made me pull at shirt collars during attacks. I get a bit anxious just looking at this picture.

There is no great place to browse Netter images online. The site that houses all of them is pretty locked down – Elsevier is still making money off the art.

You obviously know where this is going. I realize that I can’t sing the praises of one kind of medical education image while disrespecting another. From this point forward, I will keep an open mind. I will worship at the altar of Netter while others pray to their Sketchy God. I will “card-flip” and respect those who “run the list.” Though politically incorrect, I’ll probably continue to pimp when I should be questioning.

Funny story. I call table rounds "card flipping" because I flip through the index cards I make for each patient. I’ve been keeping track of patients on index cards since residency because that is what we all did. A few years ago, I caught up with my team and asked if they had time to card flip. The intern on the team looked at me blankly. The resident cut in, “Card flipping is what old people call running the list.”

Calling on the fly interrogation of medical students pimping is totally out of style. Most people have abandoned this term. I’ve been unable or unwilling to.

I do my best to channel Gilderoy Lockhart when I make this comment.

Maybe we should call it a valise.

Cliff notes, paper chase, mini cassette recorder, index cards, and here we are now. At times, the future looks sketchy …

Sketchy's image for angina has ten people and several animals in what looks like a horse farm. One of the smiths holds some tongs shaped like the number 70, which is meant to enforce the guideline definition of critical angina (occlusion above 70%). This is one of nearly 100 details that the students are supposed to pick from each picture.

By comparison, Netter reminds of the good old days when a soccer player could control the ball for more than 3 seconds without being tackled (the eighties?).

From afar, it seems more like a placebo. The time invested in rote learning is going to be as effective with or without the images. The Sketchy drawings come with long videos that describe each detail in normally-spoken English, which means the picture will take 10 minutes (more realistically 30 minutes) just for the first attempt at memorizing it.

Of course, with the de facto demise of Step 1, we may live to see the times when angina is again "a man reaching for his chest" until med school graduation.