Part 2: The other trials of thrombolysis in acute stroke were also less than persuasive

Last week I went over NINDS. This week, let's look at the other trials of thrombolysis in acute stroke. It's an eye-opener.

Last Monday I showed you the limitations of the NINDS trial of thrombolysis in acute stroke. These included statistical fragility, small effect size and randomization errors that led to baseline differences in favor of tPA.

No trial is perfect. An obvious answer to imperfect trials is other trials. Similar trials should either bolster or refute a therapy.

In the matter of thrombolysis for acute stroke, there have been many other trials. Today I will mention two of the largest—one with a nonsignificant primary endpoint and the other with a positive primary endpoint.

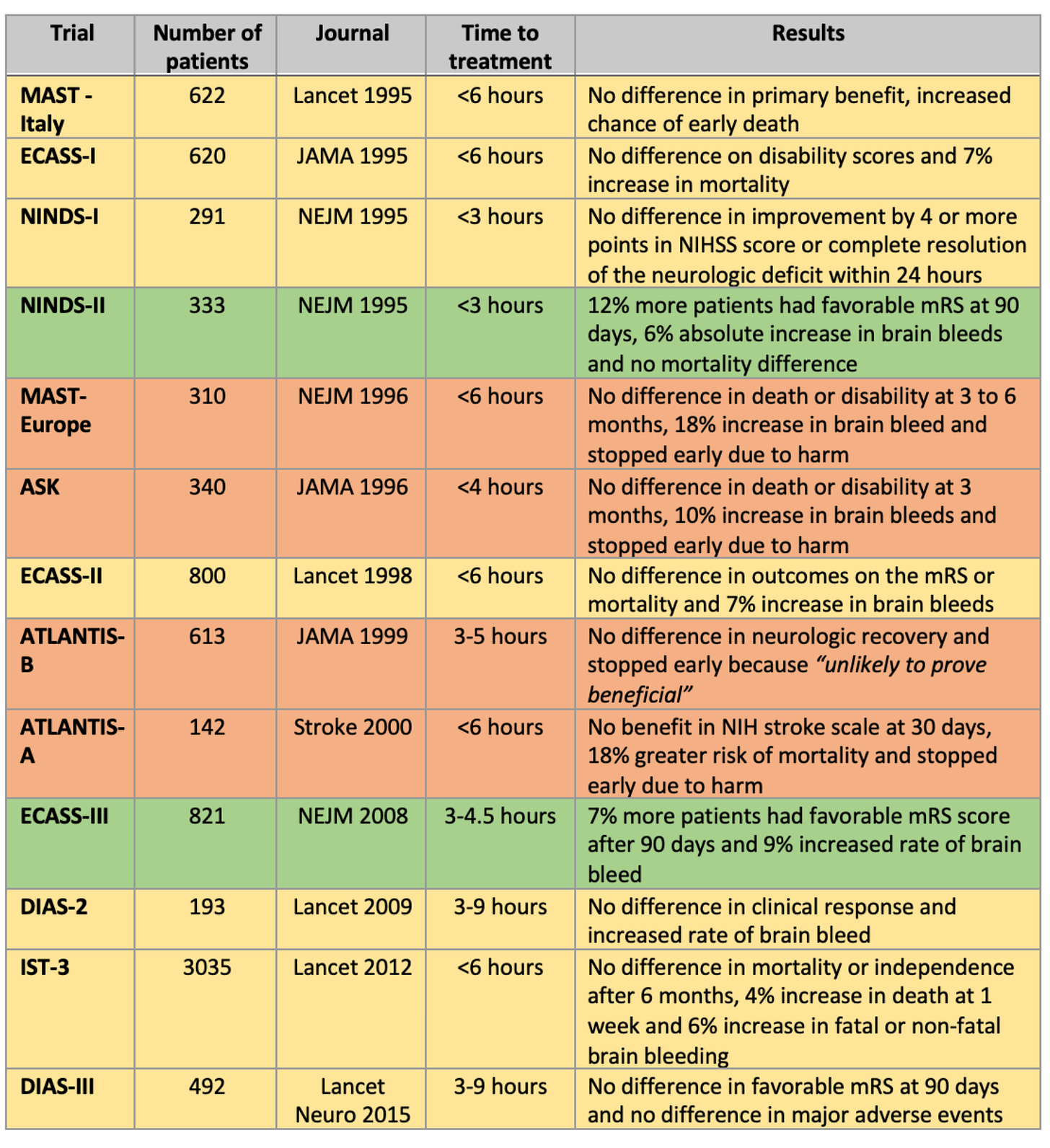

Before I tell you about the IST-3 and ECASS III trials, here is a graphic made by the Dr. Ken Milne, an emergency medicine doctor active in the thrombolysis-for-stroke evidence space.

For context, I ask you to compare (qualitatively) this picture to other accepted therapies, say, for instance, beta-blockers and RAS inhibitors for heart failure, or acute PCI for acute MI. In these spaces, the majority of trials are positive.

IST-3 Trial

The Lancet published the IST-3 trial in 2012. This was the largest (n ≈ 3000) RCT in the space. It was tPA vs placebo in 156 hospitals in 12 countries. The two unique features of IST-3 was that it enrolled patients up to 6 hours from onset of symptoms and that nearly half of patients were older than age 80.

The primary endpoint of the proportion of patients alive and independent were 37% in the tPA group vs 35% in the placebo arm. Relative risk as measured by odds ratio was 1.13; 95% CI 0.95-1.35, p = 0.18. Subgroup analyses failed to show treatment effect heterogeneity for time to administration.

Pause there. The primary endpoint did not reach statistical significance, despite 3000 patients randomized and endpoints occurring in more than a third of patients.

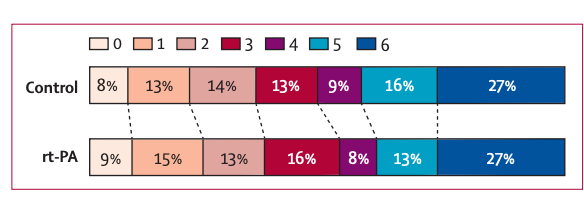

Other outcomes included an ordinal analysis which found a significant shift in the Oxford Handicap Scores to more favorable outcomes (lower is better). Here is the picture. It’s hard for me to see much different in the lower scales.

Intracranial hemorrhage was higher in the tPA group, though the primary endpoint encompasses bad outcomes because a brain bleed is covered in the alive and independent efficacy outcome.

IST-3 offers a shining example of spin--language designed to distract from a nonsignificant primary endpoint.Here is the screenshot of the conclusion in the Lancet.

The authors highlight the secondary ordinal analysis and fail to mention the nonsignificant difference in the primary outcome.

ECASS III

In 2008, NEJM published the ECASS III trial of alteplase vs placebo in 821 patients who were enrolled if symptoms occurred between 3 and 4.5 hours before presentation.

The primary endpoint was disability at 90 days, dichotomized as a favorable outcome (a score of 0 or 1 on the modified Rankin scale, which has a range of 0 to 6, with 0 indicating no symptoms at all and 6 indicating death) or an unfavorable outcome (a score of 2 to 6 on the modified Rankin scale).

More patients in the alteplase group had a favorable outcome (52.4% vs 45.2%). The odds ratio was 1.34 with 95% confidence intervals ranging from 1.02-1.76, and a p value of 0.04. A secondary outcome of four neurologic scores also favored the lytic arm (OR 1.28, 95% CI, 1.00-1.65, p <0.05).

Intracranial hemorrhage was 27% vs 17.6%. Mortality did not differ significantly between the alteplase and placebo groups.

The authors concluded that thrombolytic therapy significantly improved clinical outcomes when given between 3 and 4.5 hours after symptom onset.

If all you look at is the abstract, ECASS III looks ok. The effect size is substantial at a 34% relative increase in a favorable outcomes. And the absolute risk difference is more than 10%. Statistically speaking, however, the confidence interval gets quite close to nonsignificant, so you would not call ECASS III findings statistically robust.

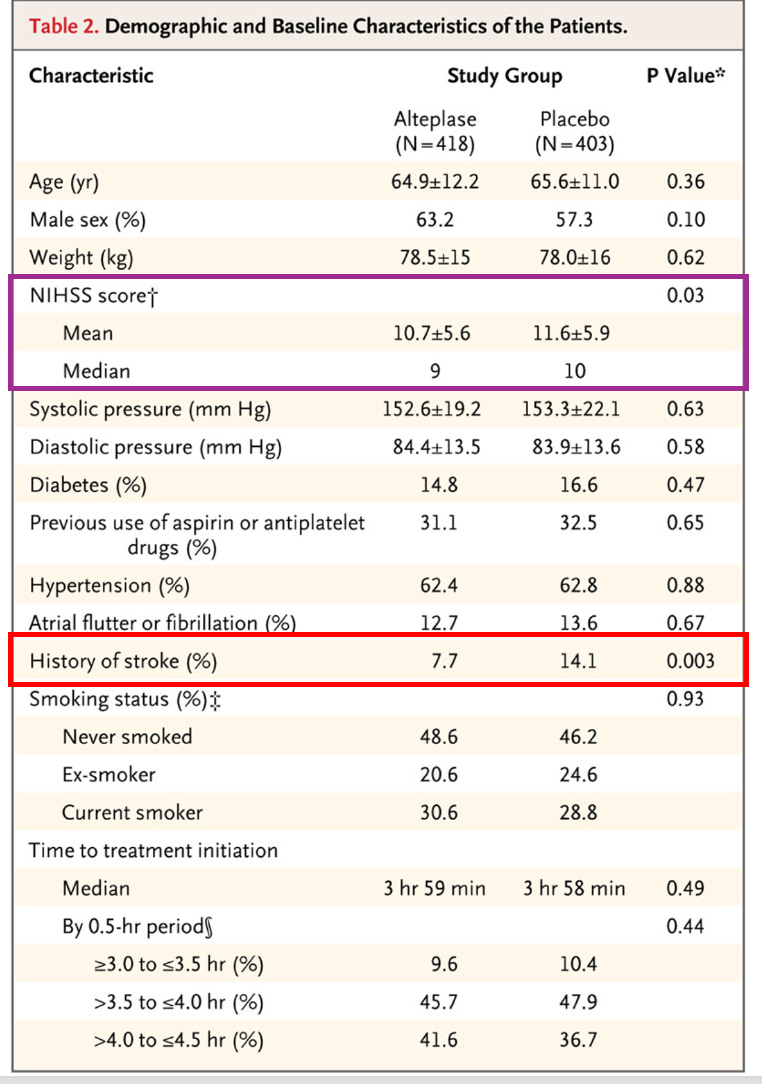

But it’s a positive trial sitting in NEJM. Yet there are problems. There are two clues from the baseline characteristics table.

The purple box highlights the fact that patients in the alteplase arm had lower NIHSS scores, meaning they had less severe strokes. We learned last week that one of the greatest predictors of post-stroke outcomes was the severity of presenting symptoms.

The red box highlights an even more dramatic difference in patients with a history of previous stroke (7.7% vs 14.1%). It hardly requires evidence to posit that the presence of a previous stroke increases the odds of poor outcomes after a second or third stroke.

Here is another place to pause and think… how does this baseline difference happen by chance? The NIHSS difference is small, but having only half the number of patients with a previous stroke is darn curious.

Of note, the original online version of the paper incorrectly listed this difference with p value of 0.03. A letter to the editor notified NEJM and the authors that the p value was 10x lower (i.e. more surprising given the assumption of no difference).

ECASS III Reanalysis

The sponsor of the trial, Boehringer Ingelheim, allowed a group of 6 authors to reanalyze the trial results based on these baseline differences. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine published the results.

The statistical analyses are complicated but the gist of the reanalyses were that the main results did not replicate.

The first major finding was that replication of the main trial’s unadjusted analysis of the primary endpoint required three conditions: a) exclusion of patients who missing baseline NIHSS scores, b) treatment of baseline NIHSS scores as categorical variables with five categories and c) treatment of the time from symptom onset to treatment as a categorical value with seven categories. None of these conditions were prespecified in the trial protocol. These were obtained from trial authors when the first attempt at replication failed.

The second major finding was that for all efficacy outcomes, their analyses adjusted for baseline differences found no significant treatment effect. Neither for the primary endpoint or ordinal analysis.

What would Proponents Say

Proponents would cite this patient-level meta-analysis which finds that most of the treatment benefit is in the less than 3-hour window.

My question, and it is a question, is: what is the validity of combining data from multiple trials that have obvious internal validity issues—mostly randomization errors that lead to baseline differences?

Conclusion

I don’t expect to overturn the practice of thrombolysis for acute stroke. It’s too late for that. What’s more, many strokes are now treated with mechanical thrombectomy—which has far more robust data.

My point in showing you this data is educational. The tension between the acceptance of this treatment and its supporting data is remarkable.

In summary, NINDS clearly has randomization errors; most other trials are nonsignificant, including the largest IST-3 trial, and the other positive trial (ECASS III) has major differences in baseline characteristics, which leads to non-replication by independent authors.

To be honest, having looked at this data, I am not sure what I would want in the setting of a stroke not amenable to mechanical intervention.

Thank you for this analysis. Many ED docs recognize that TNK isn’t great, but we have guidelines we have to adhere to… Long ago I told my husband that if I can’t consent for TNK (because my Rankin score is so bad) then I shouldn’t get it. The worse the stroke, it seems, the less likely TNK is to help.

"To be honest, having looked at this data, I am not sure what I would want in the setting of a stroke not amenable to mechanical intervention." I truly appreciate this honest reveal as your final conclusion / closing statement. Unfortunately, it leaves those of us who are less informed about managing a stroke in hard place.

At this point if I had a severe stroke I'd opt for mechanical thrombectomy if possible. Secondly, I'd

decline (or ask my POA to decline) TNK as there is no clear benefit and risk of serious harm based on the 1st of all do no harm" dictum.

The real conundrum is that in reality, it sounds like typically is little or no opportunity to discuss treatment options based on the current SOP & perceived short window of time to initiate TNK .