Race in Medicine

Figuring out if patient race should have any role in medical education

About ten years ago, I decided that I didn’t want to hear about race in the chief complaint of clinical presentations.1 Instead of “The patient is a 35-year-old African American male with cough, fever, and sputum production;” I wanted “The patient is a 35-year-old man with cough, fever, and sputum production.”

I had a few reasons. First, sometimes these presentations were “at the bedside” when I could just look at the person. Second, the race of the patient pretty much never has anything to do with the medicine. When it does, it is some trivia about ancestral exposure to malaria, sleeping sickness, or herding. Third, race seemed to be often used as a lazy and imprecise stand in for the social history, a stand in that was as likely to be wrong as it was to invite stereotyping.

In the years that followed, I learned of efforts to remove racial identifiers from medical textbooks and test questions. Because I can be pathologically contrarian — whenever people start to agree with me, I feel like I need to argue with them — I started to question my own stance. Was this move against race-based medicine, as it had become known, too extreme. Was a good idea becoming dogma and thus losing all rationality and nuance.

The arguments that race has no place in medicine are strong. I’m going to lay out some of the basic points, but for those that want to take a deep dive, Andrea Deyrup and Joseph Graves Jr. have done some great work. I drew on their work quite a bit for this piece.2

The most cogent argument that race should no longer be part of educating clinicians about diagnosis and treatment is that there is little biologic basis for race in humans. We are a lot more alike than we are different. Any two humans share 99.9% of their DNA. If you choose two Africans and one European at random, the Africans are more likely to share genetic traits with the European than with each other. (This is due to the high degree of genetic variability in Africa.)

Obviously, we do have geographically based genetic variation. This variation has enabled, shamefully, socially defined race (and thus racism). The genetic variation is not what causes differences in health. It is that people who look differently are treated differently that causes the differences.

Another critical point is that socially defined race (the only kind) – Black, Asian, European – are terribly inaccurate stand-ins for what medically important variation there is. Yes, family history is important. But assuming that two people, whom you might lump into the same race, are closely related enough to assume genetic similarity is absurd.

Race is a therefore terrible diagnostic test. We define diagnostic tests as tools that distinguish two populations, in medicine, diseased and healthy. Diagnostic tests make a suspected disease more or less likely. They are associated with high or low likelihood ratios. The likelihood ratios for race are always close to one. When considering the diagnosis of sarcoidosis for example, the patient’s history, exam findings, and imaging results dwarf the presumed diagnostic value of whether the patient is Black or white. Some of the most interesting parts of Drs. Deyrup and Graves’ talks are when they dig into the distinguishing power of race. Even when we can cite test characteristics, they are generally based on laughable data.

Lastly, there is harm in considering race as a predictor of disease or outcomes – harm beyond misdiagnosis. Primarily, the harm is that we teach students that race is more than something our ancestors made up. Medical educators encourage trainees to think in racist ways when we stereotype races by disease. There is nice work that shows that when race -- other than white -- shows up in a textbook or test question, it is always meant to suggest disease. One site, humorously but tellingly, suggests that a way to succeed on medical exams is to “be as racist as possible.” “Black people have sarcoidosis, sickle cell disease, keloids, and high blood pressure. If the person is Jewish, they have a genetic disease and will probably die from it. Japanese people have stomach cancer.”

To summarize, race is a social construct with a vanishingly small biologic basis. Race has poor correlation to genetic ancestry, which does have some importance in medicine. Race is therefore essentially useless when diagnosing disease, recommending treatments, or defining prognosis. On balance, considering and teaching “race-based medicine” is all harm and no good. Anyone can get any disease. Those who look Northern European can have sickle cell disease. Those who look Black can have cystic fibrosis.

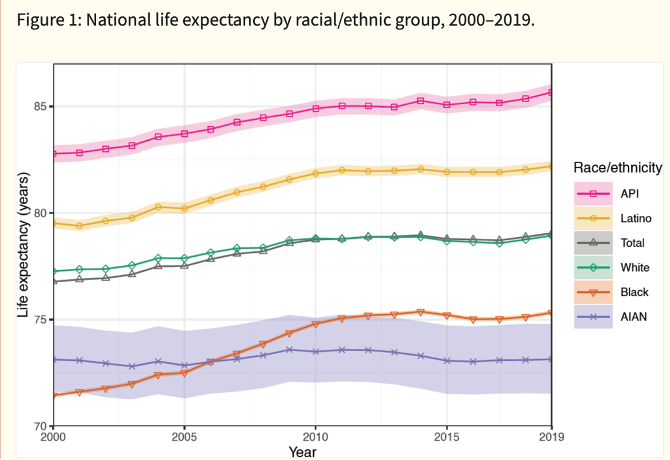

There are a few places in all this that some nuance is necessary. First, although race is a social construct with little biologic basis, it is powerful and persistent construct and this has striking consequences. All one must do is look at US life expectancy by race to be convinced.

As we work to overcome the importance of race in people’s health, I’d suggest that ignoring its existence risks failing to overcome the inequities that we have created. Teaching that race exists but has no biologic consequence, makes the differences in health outcomes between races more appalling and more in need of attention.

This is also why, although race does not belong in the chief concern or history of present illness section of the medical history, it should — probably always — appear in the social history. Becuase race, for better or worse, is important in our society, it is often part of what defines a person. Many "risk factors" that we note are weaker than being black (or poor) in America.

Second, although race correlates poorly with ancestry, it does have some correlation. When people can be helped by recognizing increased risk because of their race/ancestry, it seems wrong to me not to use this information. There are times when it would be wrong to test everyone, but correct to test higher risk people. We do this with BRCA testing. A recent NEJM article elucidated the genetic epidemiology of CKD and the clinical association of APOL1 variants with CKD in West Africans, a major group in the African American population.

The lesson here is far from profound. In medicine, you do your best when you focus on the person in front of you. That person is an individual, far more complex than what any racial stereotype could ever suggest. This is as true biologically as it is socially. When considering a patient’s diagnosis, how she might respond to treatment, what her prognosis is, the most important things are her signs and symptoms, her risk factors and family history. Her ancestry might, rarely, provide minor clues; her race is even less helpful.

I was far from the first to advocate for this change.

Good article. It’s also important for clinicians to not stereotype the white patients. When we discuss social determinants of health- we need to look at the whole person as an individual (as you mention). Labeling white people all as privileged with access to all the best things when they might in fact be from the a lower class and poor is also ridiculous. As you say- determining factors in decision making by race can be ridiculous (such as giving vaccines to people by race instead of age during covid when we know age was prob the biggest risk factor). A person’s class status has a lot to do with their health- and is probably much more similar between races than race itself in this current age.

When I read a top pediatric intensive care clinician (who is a POC) writing and reposting things about all white people in regard to their nature as human beings as all racist and privileged… that’s an issue as well. Even though this person is a friend - I wouldn’t want her taking care of my half white kids.

So yes- let’s take race out of medicine… let’s go back to critical thinking, good history taking and taking the best care of the person in front of you. And let’s not tolerate it from ANYONE

This was refreshing. The only race I truly care about, since I live close to speedway, is the Indy 500. Otherwise I love this refreshing reminder to embrace humanity. 99.9% AND that last .1%!