Sepsis Screening Decreases Mortality. Well, not really.

Critical appraisal of an article and criticism of a journal

“Don’t worry about reading – you won’t be able to keep your eyes open. The only thing you need to learn this year is how to differentiate sick people from not sick people.”

So said my program director during my internship. This comment might be one of the reasons I’ve been skeptical of sepsis screening. If there is one thing a medicine resident or hospitalist should be able to do well is identify the patients who are sick and need attention. Sepsis screening, for me, comes in many different flavors -- from EMR alerts based on lab and vital sign data to anyone being able to draw a lactate or call an RRT.

My objection to sepsis screening goes beyond the hoity-toity, philosophical, “doctors should be able to do this,” yada yada yada. I’ve predicted that any screening tool would be more sensitive but less specific than a well-trained doctor. This would mean that instituting sepsis screening would lead to escalating treatment in patients – transferring them to the ICU, escalating antibiotics, bringing in more consultants – without benefiting them.

Maybe because of my skepticism, I’ve found studies of sepsis screening interesting. I’ve also been attracted to the research because too often I see systems interventions adopted without data.1 Sepsis screening seems eminently studiable, but even a good study would be hindered by external validity. If sepsis screening was shown to be beneficial in one hospital, would it be beneficial in another, with an entirely different set of caregivers?

Article Background

With all that as background, I was excited when I saw the article Electronic Sepsis Screening Among Patients Admitted to Hospital Wards in JAMA.2 This was an impressive study. My understanding is that five Ministry of National Guard–Health Affairs hospitals in Saudi Arabia planned to adopt electronic sepsis screening using the quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) score. If patient data tripped the alert, an EMR pop-up message would appear for nurses and physicians. These alerts were backed up with training and monitoring to encourage real action.

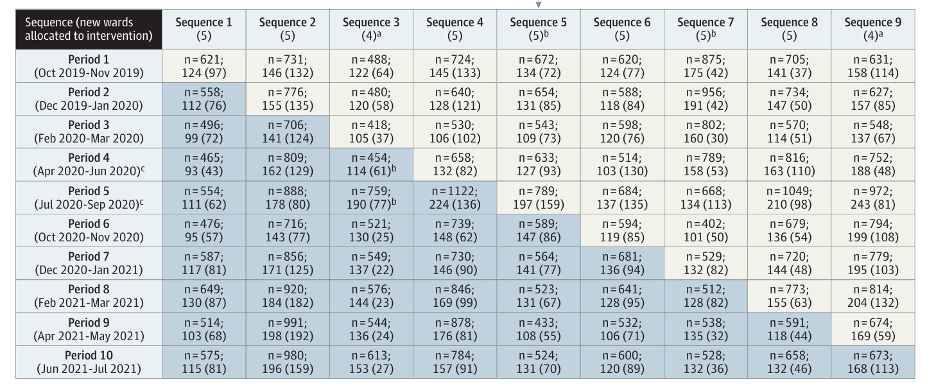

Instead of just instituting the screening, the researchers did a cluster randomization wherein the alert was sequentially adopted. This yielded an equal number of wards employing and not employing the system over the course of the study. It looked like this:

Ingenious, right?

The only problem was that the patient population would change over the course of the study – the unscreened population was studied mostly in 2019 and early 2020 while the screened population was mostly late 2020 early 2021. Thus, the results would have to be adjusted.

Outcomes and patients

The primary outcome was 90-day in-hospital mortality. Secondary outcomes included code activation, pressor therapy, initiation of HD, MDROs, and C. diff. In the end, 29,442 patients were included in the screened population and 30,613 in the control group. Median age was 59; 51% were male. Alerts occurred in 14.6% of the screening group and 17.6% of the no screening group. (These alerts only were reported in the screening group). Process measures suggested that doctors and nurses responded to the alerts with increased testing of lactate levels and fluid resuscitation.

Results

In the crude analysis, there was no difference in 90-day in-hospital mortality: 3.2% died in the screened group compared with 3.1% in the non-screened group (95% CI, −0.2% to 0.3%). When adjusted, however, there was SIGNIFICANCE! Adjusted relative risk 0.85; 95% CI, 0.77-0.93; P < .001. Screening reduced the use of vasopressor therapy and detection of multidrug-resistant organisms but increased code activation, incident HD, and C. diff infection.

Appraisal of the article (and the journal)

This article should not change hospital systems. The mortality benefit is minuscule even if statistically significant. And this is in-hospital mortality. I don’t know why this was the endpoint rather than overall mortality. Reading who uses these five hospitals in Saudi Arabia, it seems like a population that would be easy to follow. I think treatment of critical illness should always be measured against 90-day-mortality (and analyzed by RR rather than HR). Treatment of a critically ill patient is only successful if that patient is more likely to be alive 3 months out. If you are just keeping the person alive to be in the hospital for longer, this is not a success; you are helping no one.

The intervention succeeded in what you might have suspected. Screened patients were treated a little earlier so they needed fewer pressors and broad spectrum antibiotics, but they suffered from over treatment (codes, HD, C. diff).

Now to the journal. My irritation with JAMA here originates with my own mistake. When I first briefly skimmed this article — and tweeted about it — I was more impressed with the outcome than I should have been. I was busy and distracted and made a rookie mistake — looking at relative risk reduction rather than absolute risk reduction. When I went back and read the article closely, the weaknesses were obvious. But NEVER in the article — not in the abstract, not in the discussion, not in the limitations paragraph — is the issue of statistical vs. clinical significance discussed. The conclusions section runs one sentence: “Sepsis screening using an electronic alert system reduced 90 day mortality among patients admitted to hospital wards.” No mention of this being in-hospital mortality. No mention of the crude ARR of 0.1%, a NNT of 1000.

This was an impressive study, and I am sure JAMA was happy to publish it. It might end up being important, if we develop more time sensitive sepsis treatments. However, in my mind, JAMA fell short here. The job of a journal, especially a well-regarded one, should be more than taking an authors’ copyrights — without reimbursement — and printing/posting articles. Journals should help their readers understand the importance of articles. Sure, JAMA published an editorial, but it is the article that will be read and referenced going forward.3 Good editing is not easy. I know that not every article I edit for Sensible Medicine is an example of crystal clarity – hell, I can’t even catch all the typos. But JAMA is a business with a large paid staff. Please continue to publish well done studies like this one but please help your readers, many practicing physicians among them, by making the meaning of the results clearer.

In fact, chapter 5 in Ending Medical Reversal is all about this. (It’s amazing how often I reference that book. It must be really great…)

This article was actually published in December but I only read articles when they come out in print. It is part of how I streamline my “keeping up.” (Maybe a topic for a future article.)

I’ve written editorials. They do not boost your h-index.

OMG, this sepsis stuff is the bane of the Hospitalist’s existence! First of all, you know you’re in trouble when you can’t even agree on a definition. Then a predictable trade-off exists between under and overdiagnosis when protocol driven patient outcomes are deployed. Allow me to state with metaphysical certitude that sepsis alerts will not improve patient mortality at 90 days. It has just become an exercise in wack a mole EHR nonsense. There is this thing called clinical assessment at the bedside which should take priority as the mainstay of diagnosis and treatment.

Very important post Dr Cifu. Thank you.

The JAMA editorialist is the one who invented the idea that you can diagnose sepsis from EHR. He’s also one of the Sepsis-3 fathers.

The essence of Sepsis-3 is that sepsis is a disease (?) that can be diagnosed by a prognostic score (SOFA). Then they used EHR to validate the “diagnosis by prognosis” construct in large datasets.

I call it “The Angus Method”. Dr Angus is the JAMA editor. He is personally invested in the idea. It explains why this paper has such a strange spin.

I comment about it in this chronicle and in many other posts. I invite you.

Thank you again for highlighting the worrying state of critical care research.

https://thethoughtfulintensivist.substack.com/p/five-centuries-of-the-angus-method?r=20qrtz