The Study of the Week Is A Study That Did Not Happen

The RECOVER IV trial of an LV assist device vs standard care was planned, began recruiting and then stopped. The reasons say a lot.

This is the first time the study-of-the-week discusses a study that did not happen.

The main lessons of the cancelled RECOVER IV trial are hubris and dualities of interest. These lessons are key to understanding medical evidence.

Background

RECOVER IV was to study a medical device called a micro-axial flow pump. It is a cardiac assist device, which I previously discussed here and here. Briefly, it is placed across the aortic valve into the left ventricle. The brand name Impella device pulls blood from the LV and pumps it into the aorta.

One of the most common uses of LV assist devices is cardiogenic shock due to an acute MI. When an MI occurs in a large coronary artery, the downstream heart muscle stops contracting. This lack of flow can cause organ failure. A cardiologist can open the blocked artery, and the heart muscle will likely improve. But during the time of low flow, the patient can die due to organ death.

The grand idea of the Impella device is to provide support for hours to days while the injured heart muscle regains function. It makes great sense; it is plausible.

That last sentence should trigger regular readers of Sensible Medicine—because we have covered many plausible ideas that fail to pass muster in the randomized trial.

Complex Regulatory History

Impella was first approved in 2008 through a lax pathway wherein it was deemed sufficiently similar to a cardiac bypass pump. Soon after, FDA came to their senses and reclassified many high-risk devices via the 515 pathway.

In 2015, FDA approved Impella again using data primarily from a trial called PROTECT II, which compared Impella to another LV support device called the intra-aortic balloon pump.

What I type next is not a typo: PROTECT II was a) stopped for futility, b) failed to show any superiority of Impella over IABP, and c) previous studies had shown the IABP to be no better than standard care. FDA still approved the device.

Between 2009-2023, many thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands of patients, had Impella devices implanted.

Doctors and hospitals are paid extra to use the expensive device. As it is with many such devices, high usage of device brings reputational gravitas.

Finally a Trial

Can you imagine? Hundreds of thousands of devices without a positive trial. Then the Danes came to the rescue.

As I covered in April, the DANGER-Shock trial produced positive results. The Impella device reduced death by a statistically significant 12% vs standard of care. DANGER-Shock, like many trials, had caveats. One of the most important of these were that it took 10 years to recruit 360 patients. These were highly selected Danish and German patients.

Cancellation of RECOVER IV

The clinicaltrials.gov site says that RECOVER IV planned to study Impella vs standard care in cardiogenic shock in 560 patients, mostly in US centers. (More than DANGER-Shock).

Last week, however, it was stopped. The data and safety monitoring board recommended stopping the trial because of the positive results of DANGER-Shock.

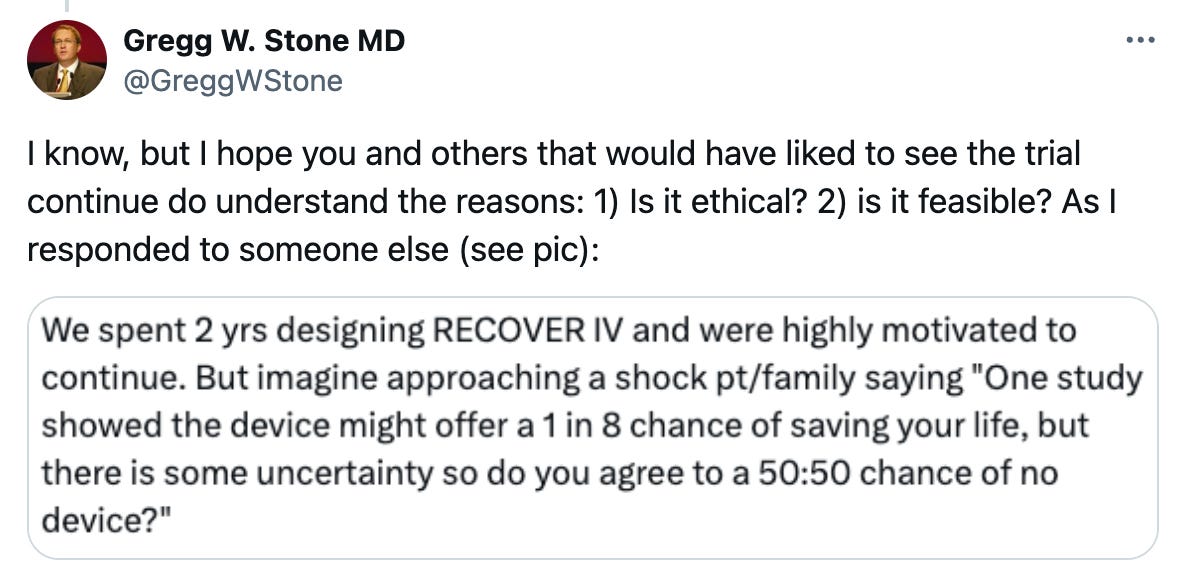

Key opinion leader, Dr Gregg Stone captured the idea in this Tweet.

The DSMB, Dr Stone, and many US leaders felt that there was no longer equipoise to conduct a trial. If there is not uncertainty of benefit, it is not ethical to randomize patients.

Hubris and Duality of Interest

I disagree strongly with this sentiment. In last week’s edition of the This Week in Cardiology podcast, I cited 8 reasons that this decision represents over-confidence from US cardiologists.

I took a picture of my thoughts about DANGER-Shock.

In sum, DANGER-Shock was a strong trial but it was not enough to settle uncertainty. US cardiologists are over-confident.

And. At the risk of sounding cynical, I must consider duality of interests.

RECOVER IV was supported by the makers of Impella. Termination of the trial due to perceived benefit of their device was clearly positive for them. US cardiologists too benefited.

I am not against this device. Interventional cardiologists have said there are patients who don’t survive without the device. DANGER-Shock supports this opinion—somewhat. But not enough.

The medical literature is replete with examples of single trials failing to replicate. Impella is a costly and invasive device. If ever we should have a confirmatory trial, it should be for this device.

That we won’t have such a trial speaks to over-confidence and dualities of interest.

Indeed, what gets studied is an important lesson in medical evidence.

John, I concur with your conclusions. There is much that is wrong with how trials are run and how results of trials are judged by the so-called FDA. What most lay people and some professionals do not realize is that the FDA equates with a particular panel in a field of medicine or science that are typically members from academic institutions. Frequently, those panels have members with private agendas intertwined with issues of ego and envy.

• I encountered this when presenting data to the FDA's Oncology Drug Advisory Committee (ODAC) for approval of the drug metoclopramide. The studies I had conducted were on patients receiving high-dose cisplatin chemotherapy for lung cancer. We used the anti-emetic metoclopramide given in high doses intravenously. At that time there were no anti-nausea or anti-vomiting drugs to support patients receiving what is called emetogenic chemotherapy. The results were impressive. ODAC rejected approval for metoclopramide. After the hearing, I asked some of the panel members why they had voted no. One replied: we did not get results similar to yours at our institution. Her institution never published results of their experience with metoclopramide in preventing nausea and vomiting for any chemotherapy drug. Another panel member said he rejected approval because there was no placebo arm. Patients getting high-dose cisplatin universally had non-stop vomiting that lasted most of the day. They required hospitalization and often the attending oncologist would use a barbituate to put the patient to sleep, who would still wake up, vomit and then fall back to sleep. Every oncologist knew about the high emetogenicity of i.v. high-dose cisplatin.

• My groups results were published in the leading journals.

Strum SB, McDermed JE, Opfell RW, Riech LP: Intravenous metoclopramide. An effective antiemetic in cancer chemotherapy. JAMA 247:2683-2686, 1982.

Strum SB, McDermed JE, Liponi DF: High-dose intravenous metoclopramide versus combination high-dose metoclopramide and intravenous dexamethasone in preventing cisplatin-induced nausea and emesis: a single-blind crossover comparison of antiemetic efficacy. J Clin Oncol 3:245-51, 1985

• Metoclopramide was immediately approved as an antiemetic when MSK (Memorial Sloan Kettering) published a ten patient trial with ten patients receiving placebo.

• What I had learned while a USPHS fellow at the U of Chicago was that in academia, if you reject a grant then that academic institution will reject your grant. Our studies were conducted in private practice. I had no ammunition to strike back and reject other "colleagues" trial results. If I had been at MSK, I am sure my initial presentation at the FDA would have been approved.

Also, there are many studies in oncology that show a survival benefit with p values of signicance (< p< 0.05) and yet the data on survival benefit may amount to 6 weeks; and this often involves a drug regimen with high frequency of serious side effects. Yet this is approved by the FDA. What we often have is a discrepancy between real world medicine in community practice and that form of medicine practiced in the ivory tower institutions. The devil is in the details. Issues such as quality of life and supportive care needs are often undiscussed.

Lastly, decisions on eligibility often are arbitrary. For example, an age cut-off for heart transplantation makes no sense if someone age 60 has multi-system disease due to a combination of bad genetics and terrible life-style choices versus a patient age 75, rejected from a trial, but with a physiologic age of 60, and in far better health than the above patient. This is what I encountered after my diagnosis of cardiac amyloidosis. I was 74 and the age cut-off was 72. Instead I was given a chemoimmunotherapy treatment that caused CHF with arrhythmias, renal dysfunction, autonomic dysfunction and a horrendous decline in my functionality.

Bottom line: principled medicine has become an oddity. Ethics in our life has taken a backseat to , ego, envy, avarice and ambition (opportunism). We need to replace such unprincipled behavior with humility, benevolence, altruism, and magnanimity.

John Mandrola has introduced us to a topic worthy of a symposium: How do we practice principled medicine? How should we be teaching our children at home and in their schools about how to conduct their life? When do we mandate that what we do as physicians focus on patient outcome an not on physician or healthcare industry income?

These new ideas speak to the demand for things that make the medical industry big, gigantic, humongous buckaroos and profits. If ever there was a true renaissance in that the medical industry would create fewer patients by providing real health, if would fizzle to a frazzle.