What I read last week 9/22/24

It was a good week of reading, three articles belonging to my favorite genre – things that we thought worked but don’t, things that should work but don’t, and things that we thought were true but aren’t.

1. Long-Term Oxygen Therapy for 24 or 15 Hours per Day in Severe Hypoxemia

We’ve known forever, or at least since I was in middle school, that chronic oxygen therapy, “home O2” helps people who are chronically hypoxic. In studies, and in practice, these people tend to be patients with COPD who have resting O2 sats of < 88%. What we have not really known is how much oxygen is enough. It would seem like more oxygen would be better and you’d be excused for asking, what could be the harm of more oxygen. Oxygen use, however, is a hassle; is dangerous around flames; impairs mobility; and the provision of tanks and concentrators is labor intensive. Many of my patients also tell me that use of oxygen limits their social interactions. They joke about their vanity but the humor disguises a real issue.

The study at hand was a classic RCT published in the NEJM. 241 patients were randomly assigned to receive oxygen therapy for 24 hours/day or 15 hours/day. The primary outcome was a composite of hospitalization or death from any cause within one year. The enrolled patients were not well. About 80% had either COPD or pulmonary fibrosis and the mean PaO2 and O2 sats were about 50mm Hg and 80%, respectively.

Results

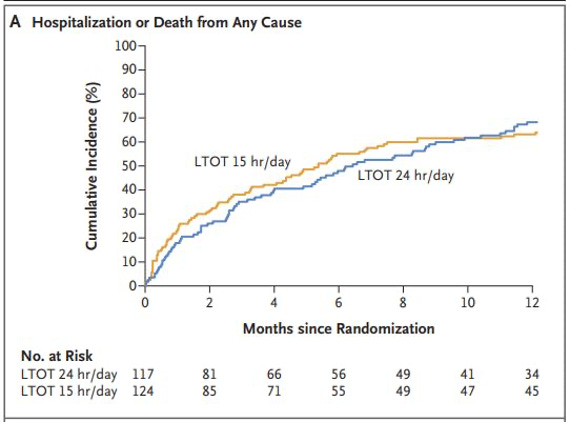

The results were clear, there was no difference in outcomes between the groups. This is despite the fact that (looking closely at table 1) the 15-hour group might have been a bit sicker. The HR for hospitalization or death within 1 year was 0.99; [CI], 0.72 to 1.36. Here is the primary figure.

When a trial is negative, we always must consider if it is a true negative or a false negative, either due to chance or to power issues. Everything about this trial suggests this is a true result.

Conclusion

What will I tell my patients my after this trial? Do your best to wear your oxygen for at least 15 hours a day. If it makes you feel better to wear it more, do that. If not, you won’t be losing anything by taking it off for 8 or 9 hours a day.

2. Community-Based Cluster-Randomized Trial to Reduce Opioid Overdose Deaths

Last week, we got the (at least to me) shocking news that opioid deaths are down in the US. While this is cause for celebration, there are still far too many. Last week, the NEJM included this study of the effectiveness of a community-engaged interventions to reduce opioid-related overdose deaths. Like the oxygen study, this was an impressive piece of work. The study was a community-level, cluster-randomized trial, including 67 communities in Kentucky, Massachusetts, New York, and Ohio. Half the locations received the intervention and half were “wait-listed” for it. The randomization was stratified according to state and the trial groups were balanced within states according to urban or rural classification, previous overdose rate, and community population. The primary outcome was the number of opioid-related overdose deaths among community adults.

What was the intervention? Community coalitions were established that included residents who were somehow involved in the opioid use disorder crisis. Coalitions assessed the local effect of opioid overdoses using data to understand gaps and resources. They then implemented communication campaigns promoting opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution, the use of medications for opioid use disorder, and messages to reduce stigma through print, digital, radio, outdoor, and social media channels. These were said to be “evidenced-based strategies.” I am far from an expert in this field but after pulling the references and skimming the articles, the term “evidence-based” is being used loosely here. Most interventions were supported by observational data.

Results

There was no difference between population-averaged rates of opioid-related overdose deaths between the intervention and the control groups, 47.2 deaths/100,000 population vs. 51.7 per 100,000 population, respectively (RR: 0.91; CI, 0.76 to 1.09; P=0.30). The effect of the intervention did not differ according to state, urban or rural category, age, sex, or race or ethnic group.

Conclusion

This is a depressing study. It reminds us how tough it will be to reduce opiate deaths, at least through community intervention. There are reasons this study’s intervention might have failed. Maybe the interventions, “evidenced-based” though they might be, don’t work. Maybe we need to do a better job implementing them. Intervention communities only implemented 615 strategies from the 806 selected by communities. Furthermore, only 235 (38%) had been initiated by the start of the comparison year.

What I found interesting about this study was that it was the sort of cluster RCT, run during the pandemic, that some people (ahem) were screaming for to test COVID control interventions. It seems like it was possible.

Ok, this might be my favorite paper of the year. It is certainly my favorite pre-print ever. I found this article through the Ig Nobel awards.[i]1 The article was written by Saul Justin Neman. Dr. Newman is a PhD interdisciplinary scholar at the Leverhulme Center for Demographic Science, Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford. His article is neither a short nor easy read, but it is more than worth your time. He took a deep dive into data from the areas of the world filled with long-lived people to see if there might be something besides goat cheese, yogurt, long walks, and fresh air. What he found was poor birth records and evidence of pension fraud. Maybe I will just quote the last two sentences of the abstract that got me to read the article.

Finally, the designated ‘blue zones’ of Sardinia, Okinawa, and Ikaria corresponded to regions with low incomes, low literacy, high crime rate and short life expectancy relative to their national average. As such, relative poverty and short lifespan constitute unexpected predictors of centenarian and supercentenarian status and support a primary role of fraud and error in generating remarkable human age records.2

Even after poring over this paper, I can’t tell if Dr. Newman has totally debunked the whole Blue Zone fad or if it has only taken some of the shine off of it.3 What I love about the article is that it shows that the real story is often so much more interesting than the ones fed to us by popular media (i.e. churnalists) and books written by physicians.

Enjoyable baseball factoid this week. On April 22, 1970, Tom Seaver (otherwise known as Tom Terrific or Adam Cifu’s boyhood hero) had 9 strikeouts with 2 outs in the sixth inning of a game against the San Diego Padres. He struck out the next 10 batters to close out a 2 hitter, a 2-1 victory for the Mets.

If you don’t follow the Ig Nobel awards, you should. Their tag line is, “Research that makes people LAUGH...then think.”

Of note, Sardinia, Okinawa, and Ikaria are all on my list of places I want to visit.

I would really appreciate if a Sensible Medicine reader with a little more time than me could update the Blue Zone Wikipedia page.

I recall years ago reading the first words to the section on oldest humans in the Guinness Book - "No area is more rife with fraud and deception than age" or words to that effect. Wouldn't that be something if the whole Blue Zone fad turned out to be BS?

The Blue Zone paper provides a lesson far beyond its subject. The so-called Blue Zone studies have generated an industry worth what I guess has made billions for those who have jumped on the fad to sell their Blue Zone related products. I, for one, have always been skeptical of the Blue Zones; it didn't pass my smell test. The research by Dr. Neman cracks open a window on how popular science misleads the public but enriches those who would take advantage of it. I am not so much criticizing those who profit from fads as I am criticizing a gullible public.