Adam Should Not Feel Chagrin When Disease Occurs

There are two approaches to medical practice. Which one do you favor?

I took the title from Adam’s commentary on Friday. Do read his excellent essay on the limits of preventive healthcare.

Most striking to me, and the reason I feel compelled to write, was Adam’s comments about feeling chagrin when one of his patients develops a preventable disease.

The notion of regret about “preventable” disease brings me to the two great philosophies of medical practice—a variant of Thomas Sowell’s conflict of visions.

Adam’s regret follows the unconstrained vision. An idea that if all were done perfectly well disease could be wiped from humanity.

Similar ideas include getting a coronary artery calcium scan to avoid a heart attack, a mammogram to prevent breast cancer and having sepsis algorithms so no patient with infection ever dies from sepsis. I’ve even known doctors to fire patients who have atrial fibrillation (AF) and refuse to take oral anticoagulation.

Patients too fall into similar categories: some are maximizers who are game to go along with interventions however unlikely these are to improve outcomes. Some patients are minimizers who want to be left alone.

The benefits of the unconstrained vision in medical practice is that it may align with a patient’s values, and it will occasionally prevent a bad outcome. Screening for disease may not work (harm = benefit when averaged over many), but there are surely individuals saved from a bad outcome.

Another benefit of unconstrained thinking is that it can spur innovation. Ablation now vs 1990 is shocking. We want unconstrained thinkers in research labs.

My philosophy of medicine—as both patient and doctor—is more consistent with a constrained vision. I liken this to the shit happens camp. Constrained thinking should not be equated with nihilism. We don’t ignore things like high blood pressure, obesity and diabetes.

I have come to this view perhaps because my field of electrophysiology began as a fixing profession. The golden era of our field came when we learned to ablate supraventricular tachycardia—a problem related to a fluke of nature. And half of EP involves cardiac pacing—a problem of aging. In the past, EP doctors existed to help people who ask for help; you can’t prevent SVT or aging.

More and more, though, EP has moved into the low statistical yield area of prevention. Take stroke prevention in AF.

Everyone knows that AF, along with other risk factors, confers a higher probability of stroke. A long-time ago, we showed that anticoagulation with warfarin provided a net benefit to patients at high enough baseline stroke risk. Then the new anticoagulants were shown to be slightly better and more convenient than warfarin.

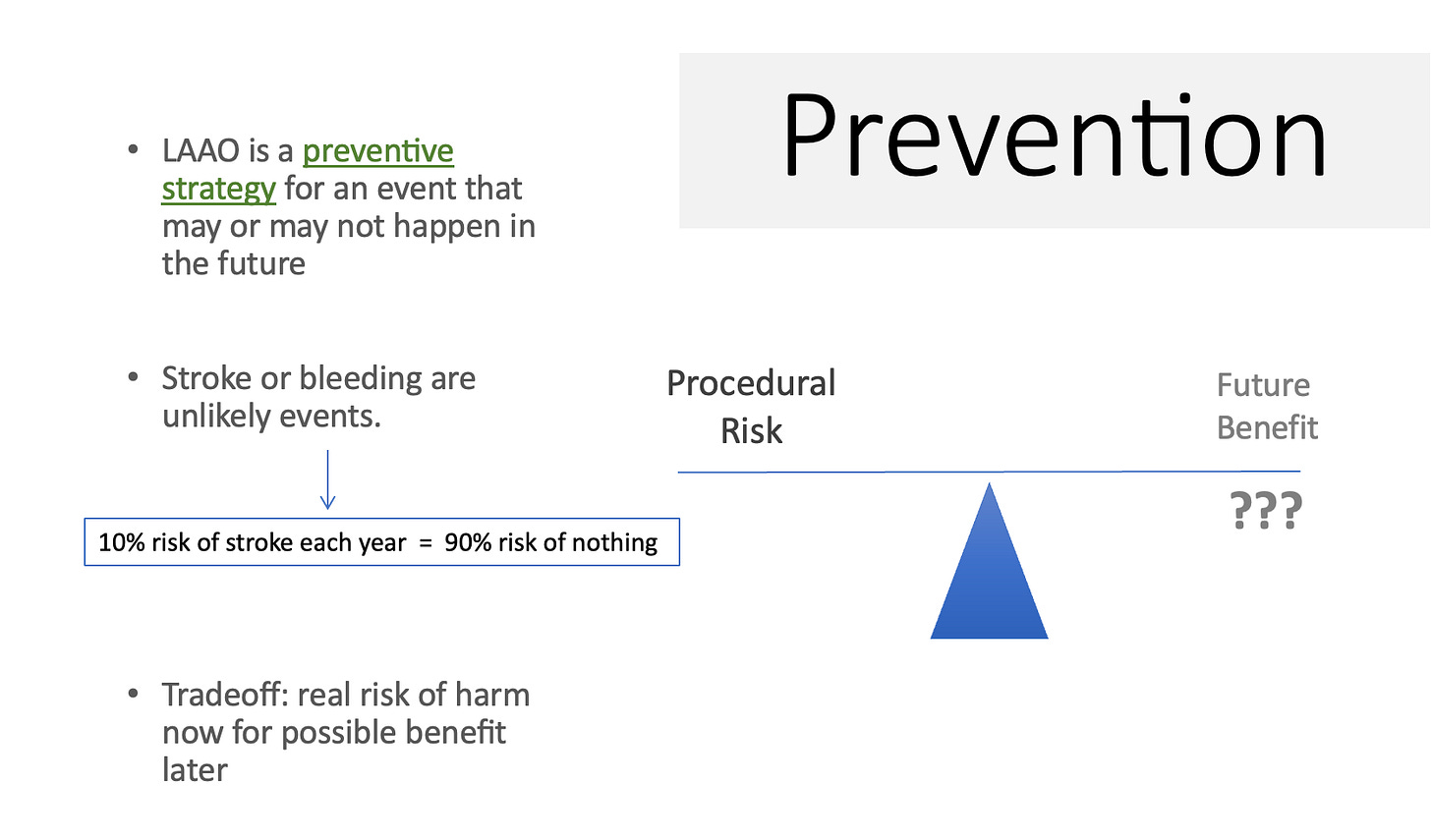

Now many of colleagues believe a device that plugs the left atrial appendage may provide long-lasting stroke prevention without the need for oral anticoagulation. Arguments for and against LAAC are complicated, but at its core, is a conflict of visions.

Unconstrained thinking has it that stroke and bleeding are preventable events in patients with AF. To wit…as the skill of placing the device (with such things as sophisticated imaging) and the iteration of the device improve, we eventually get to the point of perfect LAA closure. Then stroke and bleeding will be largely eliminated.

I don’t feel that way. Here is slide that I show at the beginning of lectures on LAAC.

It points out that patients who have LAAC face a finite risk of procedural complications. You cannot do anything to a person without risk of harm. Let’s say it is 2%. Now you have to believe that that device will provide a > 2% better probability of stroke prevention and bleeding reduction going forward.

Thus far, proponents have not shown that. The most recent trial showed that it was worse than standard care. But that’s my point here.

My point is that the patient who accepts the 2% procedural risk is not likely to have either stroke or bleeding in the future. We have risk calculators that crudely estimate future stroke risk. Let’s say our patient has an estimated 8% yearly risk of stroke. This is considered very high, but the constrained thinker realizes that is a 92% chance of no stroke.

The constrained thinker also understands the fact that the population attributable risk of AF for stroke is less than 20%. Meaning that even if we eliminated all AF from a population, we’d only reduce stroke by 20%. Stroke comes from many causes.

This is why I feel the next LAAC trial done in high-bleeding-risk patients should have a “do nothing” arm. Patients randomized to that arm avoid the 2% upfront harm of us trying to help. That’s a huge head start.

Constrained thinking is also why I don’t struggle when an informed patient declines an anticoagulant. Though I do explain the asymmetry (low probability/high consequence) of stroke risk.

This philosophy applies to much of my thinking about prevention.

While unconstrained thinkers believe in doing more to prevent bad things; I see the potential problems we can cause trying to help too much. One of my greatest joys in medicine is when a colleague calls me to complain that a 96-year-old patient of mine has not a cardiac test in 20 years. Grin.

You might wonder which philosophy is correct. The answer I believe is trials.

To the unconstrained thinkers who love coronary artery calcium imaging, my take is show me a trial that finds benefit over standard care. If you say a trial is not possible because it would require millions of patients, then that is an answer: it doesn’t affect outcomes if you need that many patients.

Constrained thinkers believe that before we intervene on healthy people who complain of nothing, we should have strong evidence of benefit. For instance, we check for high blood pressure because the evidence of treating it is strong. 50-year-olds with high blood pressure live to 90 because some one checked their BP.

None of this should be depressing. And I bet Adam is mostly a constrained thinker. He’s helped a ton of people in his life—by both intervening and not intervening.

Medicine is a great field. We excel most when we treat people who ask for our help.

Illness is part of life, and we hope that when it comes to us, there are skilled people there to help us.

What a great piece. Thanks John.

Dr. Mandrola, I have followed you for years, and in no way do I mean to lessen your previous writings by saying that your statement that you are in the “shit happens” camp is my favorite of all! I am a retired Occupational Therapist and have read many history and physicals. As my years of experience increased, I saw that the H and P did not tell the whole story. So many patients with complicated histories were functioning very well, and many who had very few issues were floundering. And many who did everything “right” had cancer or something else, and others who broke all the rules were not all that debilitated. I like to think living “right” is a hedge against shit happens, so that is what I live. But as I have gotten older I also have decreased the pressure I put on myself, because of the reality of shit happens. And also, in my opinion, that “super natural” only means we humans have not yet figured out the sophistication of the cosmos and the divine (and we never will.) Thank you for all you do!!!