Do doctors help healthy people?

During a recent episode of “This Fortnight in Medicine”, I presented the 2015 NEJM article, Polysaccharide Conjugate Vaccine against Pneumococcal Pneumonia in Adults. This article assessed the benefit of the Prevnar 13 vaccine compared to a placebo. If you want our full take on it, including some withering commentary from Dr. Foy, give the podcast a listen.1

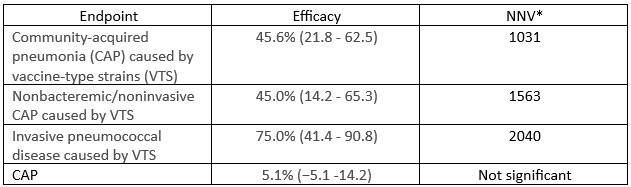

These per-protocol results represent the TLDR for the article:

*Number needed to vaccinate

The middle column shows that this vaccine is moderately effective. However, the NNVs tell us that few people benefit from vaccination. Somewhat ironically, the high NNVs are partly due to the success of childhood pneumococcal vaccination, which has reduced the organism’s prevalence in the population.

A newer version of this vaccine, Prevnar 20, is recommended for all people 50 years or older. Therefore, a highlighted “best practice advisory” appears in the electronic medical record of pretty much every patient I see. This is for a vaccine which will almost certainly not prevent pneumococcal pneumonia in any patient I give it to, let alone prevent community-acquired pneumonia, hospitalization, or death.

As a primary care physician, I felt a bit depressed after reading this article. Pneumococcal vaccination seems like a no-brainer, but it helps few of my patients. Spiraling, I considered all the things I am supposed to do during a healthy visit appointment. Consider me seeing a healthy 60-year-old man in December of 2025 who comes in for a check-up. Besides measuring his blood pressure, the value of which I will not argue, I am encouraged to do the following:

Offer the COVID, Flu, RSV, shingles, and Prevnar vaccines

Discuss colon cancer and prostate cancer screening

Order some blood work: hemoglobin A1C, lipid panel, and, if he hasn’t been tested, hepatitis C and HIV.

If I had time, and looked into the United States Preventive Services Task Force grade A and B recommendations, I would screen for depression, suicide risk, fall risk, and alcohol or drug use. I would also counsel regarding a healthy diet and physical activity.2

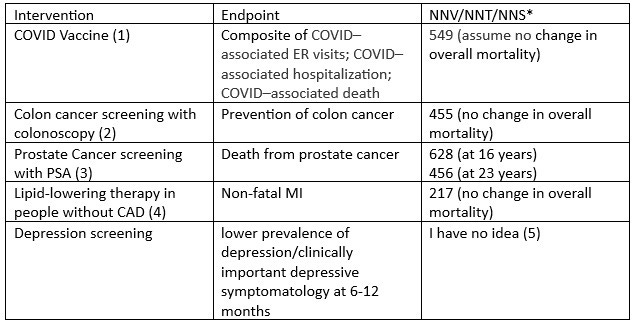

The effectiveness of many of these recommendations aligns with Prevnar. Just for a flavor:

*Number needed to vaccinate, treat, or screen; 1; 2; 3; 4; 5

Before really tying myself into knots about how little I do for the people who see me when they are not sick, a few caveats. First, these numbers should not be surprising. Healthy people coming to a doctor are generally, well, healthy. The likelihood of suffering any of the endpoints in column two is small. Also, our treatments aren’t perfect. Even things that are gospel in medicine — aspirin at the time of a STEMI or a statin in someone with CVD — have NNTs to prevent death of 42 and 83, respectively. The result is that we need to screen a lot of people to find someone at risk and then treat a lot of people to benefit someone.3

Second, a high NNT is not incompatible with effective medicine. I saved the life of a 52-year-old man whom I screened for prostate cancer and found Gleason 8 disease confined to his gland. I saved the life of a 54-year-old woman whom I screened for colon cancer and found an adenocarcinoma in a 2 cm polyp.

However, much of our healthcare does little for people’s health. Primary care doctors are bogged down recommending interventions that help only a few people. The benefit to the few might be offset by the harm we cause with overtesting, overdiagnosis, and overtreatment, by the cost to our country, and to the mental health of our doctors.

How did we get here?

Partially, we got here because of our beneficence. A career working in healthcare has taught me that the overwhelming majority of doctors act only with the intention of helping their patients. Beneficence sometimes overwhelms our intellectualism. Our benevolence blinds us to how unlikely it is that our actions will help.

Our own success has also blinded us. Our vaccines have rid the world of smallpox and (at least in the areas of wealthy countries where people appropriately vaccinate their children) scourges such as tetanus, diphtheria, measles, and polio. We can prevent colon cancer and cervical cancer. We can cure breast cancer and melanoma, even when they present at advanced stages. These successes -- in some areas, with some people -- make us feel like everyone can benefit from our healing touch.

Misconceptions about our power make us sensitive to feeling chagrin; chagrin that comes from ourselves and from our colleagues. When someone sickens or dies from a “preventable” disease, we experience pain, guilt, and embarrassment. We feel chagrin when a patient presents with colon or prostate cancer after not having been screened. We feel it when a patient presents to the urgent care with shingles, having not gotten their vaccine, or with “inadequately controlled” blood pressure.

Not all of our problems come from us being blinded by beneficence and medicine’s success. There is also, of course, profit. The benefit of adult pneumococcal vaccination is, at best, small. For some, vaccination might be the right decision, for others, not. What encourages the recommendation that every adult over fifty receive the shot? A whole lot of money. Given the prohibition on generic vaccines, a company able to get a vaccine recommended for every adult over a certain age inherits a bottomless trust fund.

Where does the primary care physician draw the line on what to recommend to healthy visitors? What does it take to make us more humble regarding our ability to prevent disease? At what NNT/NNS/NNV do we not feel chagrin when someone becomes ill? Can we—or the FDA or guideline committees—say no to preventive therapy that works for a few but costs us all?

I wish I had a support number for primary care physicians to end this piece with.

It is the second article covered; the discussion starts at 23:10.

Really, I would probably just refer him to my Life My Way post.

If the prevalence of a disease in an asymptomatic population is 1/1000 and your NNT is 100, your NNS is 100,000.

As a healthy 75-year old, what I need at the required annual or semi-annual visit is information about what I can do to maintain a healthy lifestyle in terms of nutrition, weight and the best quality diet in terms of protein and other nutrients, supplements that may be useful or current news in the media about nutrition and health that should be disregarded; discussion about exercise opportunities that will keep me moving physically and activities in the community and about maintaining intellectual health. I am not interested in vaccines or a lot of preventive screenings which waste my time. It really is about quality of life at this point.

A wise and humble piece that all physicians can learn from. We accomplish both more and less than we think. We must content ourselves with the small victories and incremental improvements. We can also all do more to promote wellness. I tell most of my patients that they have more control over their health than I do.