Lifestyle, Statins, or Both?

The false dichotomy between statins and lifestyle is a poor way to promote cardiovascular health

The study of the week will take a short break. I head to Curitiba Brazil tomorrow for the Brazilian EP society meeting. I have five lectures. I will be back next week. And there will be plenty of studies to choose from because we are entering the fall season of medical meetings.

This week, Sensible Medicine features a guest column from Zachary R. Caverley, a Cardiology Physician Assistant working in the Northwest coast of Oregon. It’s an extremely thoughtful post on statins and lifestyle. JMM

Lifestyle, Statins, or Both? By Zachary Caverley, PA-C:

Statins have fallen on hard times in the public square. A search of the word “statin” in Amazon books brings up a litany of titles that assure readers statins are just one facet of the ongoing “cholesterol myth.” Youtube and Substack often fare no better, promoting journalists and podcast hosts who have either debunked statin effectiveness or imply that they have replaced much more helpful lifestyle interventions.

While I would agree that statins are over-prescribed in patients who may experience only a marginal benefit, it’s the problem of promoting the idea of a binary choice between lifestyle changes or statin therapy that I take issue with.

A look at the statin-skeptical literature exemplifies this problem. Barbara H. Roberts writes in her book, The Truth About Statins: Risks and Alternatives to Cholesterol-Lowering Drugs:

“I hope that the forgoing chapters have persuaded you that a prescription for statins should not be taken lightly. Chances are that your physician does not know that even if you already had a heart attack, you can lower your risk of another without lowering your LDL cholesterol, as was shown in the Lyon Diet Heart Study.”

This study promoted by Roberts and others was a randomized trial on dietary changes after patients suffered a heart attack. Subjects were randomized to a Mediterranean diet vs whatever diet their physician had advised. The Mediterranean diet arm certainly had less cardiovascular events than the control group, but the trial says nothing of the superiority of dietary interventions over medical therapy. The authors were quite clear medical and lifestyle interventions are synergistic:

“...it should be emphasized that taking 1 or several drugs prescribed by their attending physician, as most of the patients did in the 2 groups of the present trial, is not incompatible with the adoption of new dietary habits. This trial even supports the view that pharmacological treatment (for instance, with aspirin) and dietary prevention had additional and independent beneficial effects.”

I should add the Lyon Diet Heart Study took place in the late 1980s and early 1990s before the widespread adoption of statin therapy. Only a quarter or so of patients in the experimental arm were on lipid lowering therapy and it is not clear how much of this was composed of statins.

Like Roberts’s assertion, Aseem Malhotra tells us right from the cover of his book that statins can be replaced with lifestyle interventions. One of the key arguments in A Statin Free Life: A revolutionary life plan for tackling heart disease – without the use of statins is these drugs are not only less effective than promoted, but also, most patients stop taking them anyway. He writes,

“What is quite astounding is that studies have revealed that the majority of patients prescribed a statin (up to 75%) in the community stop the drug within a couple of years.”

How this information qualifies as “astounding” is anyone’s guess. It is no secret that medication adherence is poor in general and tends to worsen the more pill burden increases. The issue is not specific to statins.

Malhotra also leaves out the other side of the coin: people tend to be just as bad at sticking to lifestyle changes as they are with medications. Surveys, for example, in patients already diagnosed with heart disease show disappointingly low numbers for adherence to smoking cessation and exercise recommendations. Gregory Katz put the problem succinctly: “it’s too easy to get into the trap of ‘let’s give it a few months’ before we end up a few years later with longstanding and untreated high blood pressure or lipids.”

The main question that inevitably arises is how does taking a statin stop patients from also trying to improve their health through improving the diet, smoking less, and exercising a bit more?

Maryanne Demasi has the answer. She wrote in a separate post that prescribing statins can cause patients to defer helpful lifestyle changes “under the mistaken belief that they are ‘protected,’ a behavior referred to as statin gluttony.” The study she cites is a cross-sectional analysis of NHANES survey data indicating statin users having higher calorie and fat intake over time compared to nonusers.

Claiming this study proves statins causes unhealthy lifestyle changes is an improper use of a cross-sectional study. Such analyses are fine for assessing the prevalence of an issue, but cannot prove causation, and thus would not be able to prove taking statins cause poor lifestyles.

An analysis of the randomized trials on statins did find that weight increased on statins compared to placebo, but by less than 1lb on average. This effect was not consistent when comparing higher dose statins to less intensive regimens, making the claim even more suspect.

One could still argue that statins may lead to debilitating muscular side effects that will lead to less physical activity. I have seen my share of patients that reported difficulty with exercise that improved after stopping their statin, but two trials call into question the claim that statins, in general, would lead to exercise intolerance.

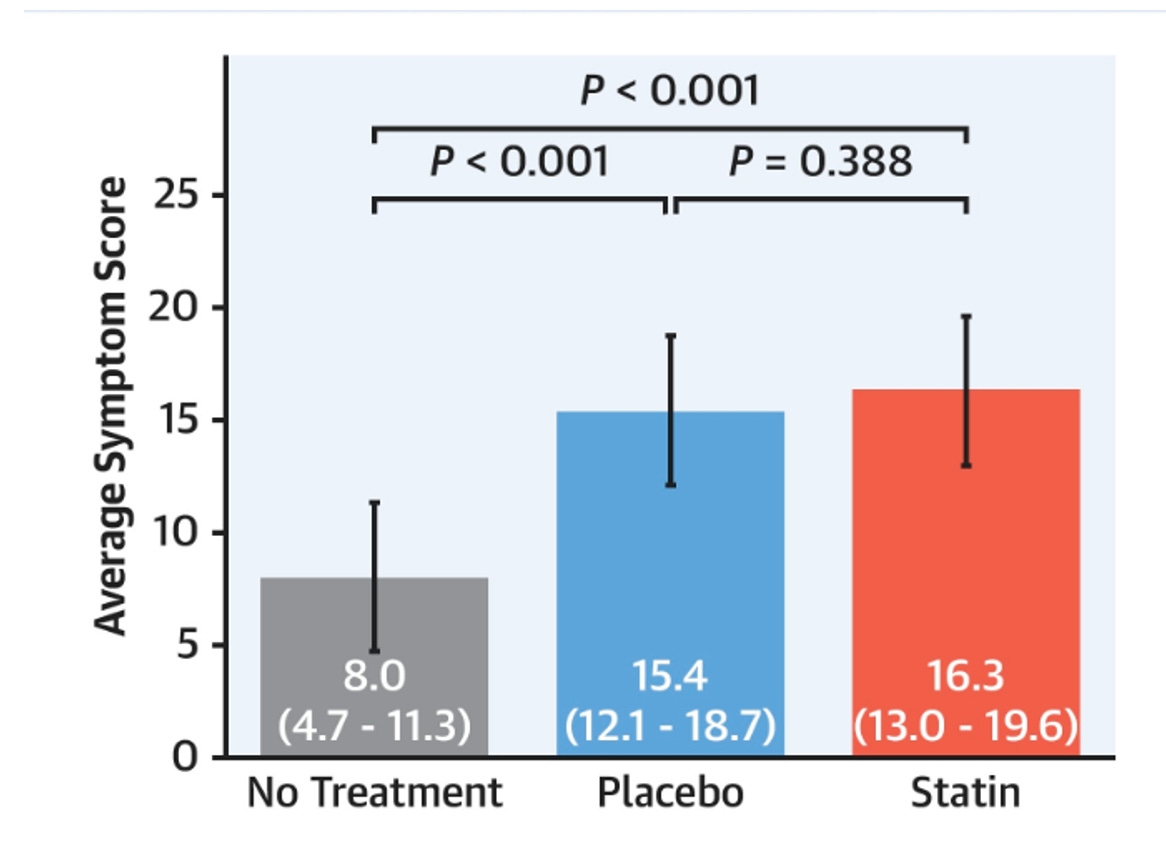

The SAMSON trial recruited patients with a history of statin intolerance and randomized them to a bottle containing statins, placebo pills, or nothing at all. Subjects were asked to report side effects, and the results indicated (see chart below) there was no significant difference in side effects on a statin versus placebo.

This indicates at least some of the side effect resolution when stopping statins is due to the “nocebo” effect – the psychological expectation that a drug will cause side effects that then improve after discontinuing it. Just as notable was the finding that 50% of patients were able to restart their statin despite having a previously reported intolerance. (Editor’s note: I have written on this trial here and interviewed the PI here.)

The other study assessed statin users during prolonged, moderate intensity exercise (“moderate” might be a misnomer here. This was a not a few minutes on an exercise bike – we are talking up to 50 km per day of walking at a time).

Patients suffering statin-related muscle complaints and those without were compared before and after exercise. Both groups saw roughly similar increases of muscle-related symptoms per the scoring system used, indicating statins did not exacerbate muscle complaints from exercise.

Clearly, not everyone needs or will tolerate a statin, but for many patients, stating lifestyle changes can be pursued in lieu of taking one is an over-simplified way to frame this problem.

Statins and lifestyle changes are just two tools in the patient-provider toolbelt to help lower the risk of cardiovascular events, and neither is mutually exclusive to the other.

Patients and clinicians alike should be addressing cardiovascular risk from both angles if we really want to help patients lead heart healthy lives. ZAC

Is this the benefit?

“The relative risk reduction for those taking statins compared with those who did not was 9% for deaths, 29% for heart attacks and 14% for strokes. Yet the absolute risk reduction of dying, having a heart attack or stroke was 0.8%, 1.3% and 0.4% respectively.”

https://theconversation.com/benefits-of-statins-may-have-been-overstated-new-study-175557?form=MG0AV3

That doesn’t look like much of a benefit to me. Especially when you consider that industry funded studies are biased in favor of their product. For instance, wasn’t the highly influential JUPITER study stopped early? If we had a technique for removing the proven industry bias, then what are the benefits? Why should we trust studies when we know they are biased, especially when the alleged benefit is so small?

https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn3781-research-funded-by-drug-companies-is-biased/?form=MG0AV3

If the side effects are nocebo, why is it that people experience the same list of side effects for statins, but not other drugs. I would think every drug would have the same problem, with an identical list. Is it something about the name “statin” that causes users to list the same side effects? What are the harms of taking these drugs for 25 years? How could anyone know?

How do we know statins and lifestyle improvements are better than just lifestyle improvements? Is there a randomized study that compares the two? I can see how it’s plausible that statins create a false sense of security that might inhibit someone from taking better care of themselves.

What about the proven risks, are they irrelevant?

https://www.bmj.com/content/381/bmj-2022-071727?form=MG0AV3

Kudos to the author for informing himself by reading Malhotra and Demasi before weighing in. That said, the dichotomy is real and can be summarized by: "Do you go with lifestyle interventions which will not only lower your cardiac risk but will also improve every aspect of your health and vitality for the rest of your life including lowering your risk of dementia, or pop a pill where it is not clear that the benefits even outweigh the risks and which will be a drag on your overall health for the rest of your life, including possibly increasing your risk of dementia?"

Just an anecdote but a true one: a friend developed joint pain from statins but when he stopped, the pain did not subside. He ended up on prednisone for a year, purely a result of the statins. I don't know the percentage of statin users who develop similar problems but I do know the percentage in those who adopt lifestyle changes: zero. Quite the opposite in fact. That's the dichotomy - positive health benefits all around vs questionable risk/benefit.