Post Herpetic Churnalism

An objection to a New York Times alert

There I was, enjoying a Wednesday morning clinic session, when my phone vibrated with a notification from the New York Times.1 I looked down, wondering what disaster was afflicting the stock market, our country, or the planet, when I see: Shingles Vaccine Can Decrease Risk of Dementia, Study Finds. Instead of being annoyed, I thought:

1. Great, this must be a piece of churnalism that I can write about on Sensible Medicine.

2. Thank God this is not the kind of health news story that will mean people will start calling to tell me that they regret having followed my advice.

Part 1: Get your shingles shot

I encourage all my patients over 50 to get the shingles vaccine, Shingrix. This recommendation is a great example of evidence-based medicine. Epidemiology and pathophysiology tell us that shingles (and related postherpetic neuralgia) is common, and that vaccination should decrease its risk. We have data showing that the Shingrix vaccine is remarkably effective (with efficacy of ~ 90%). My clinical experience also supports the recommendation. I have seen too many functional, older people turned into frail, elderly patients by a bad case of shingles.

Part 2: The study

The study the Times was reporting on was an impressive one, published in Nature, with the nice editorial by Anupam Jena. If you wanted to prove that the shingles vaccine decreases the risk of dementia, you would do an RCT, like the one in NEJM linked to in part 1. However, instead of following people for 3.7 years and with an endpoint of shingles, you’d follow people for a decade and the endpoint would be incident dementia. Of course, this was not the study done in 2016, because who would have thought that preventing shingles would reduce the risk of dementia. Today, randomizing people eligible for the shingles vaccine to placebo would be unethical.

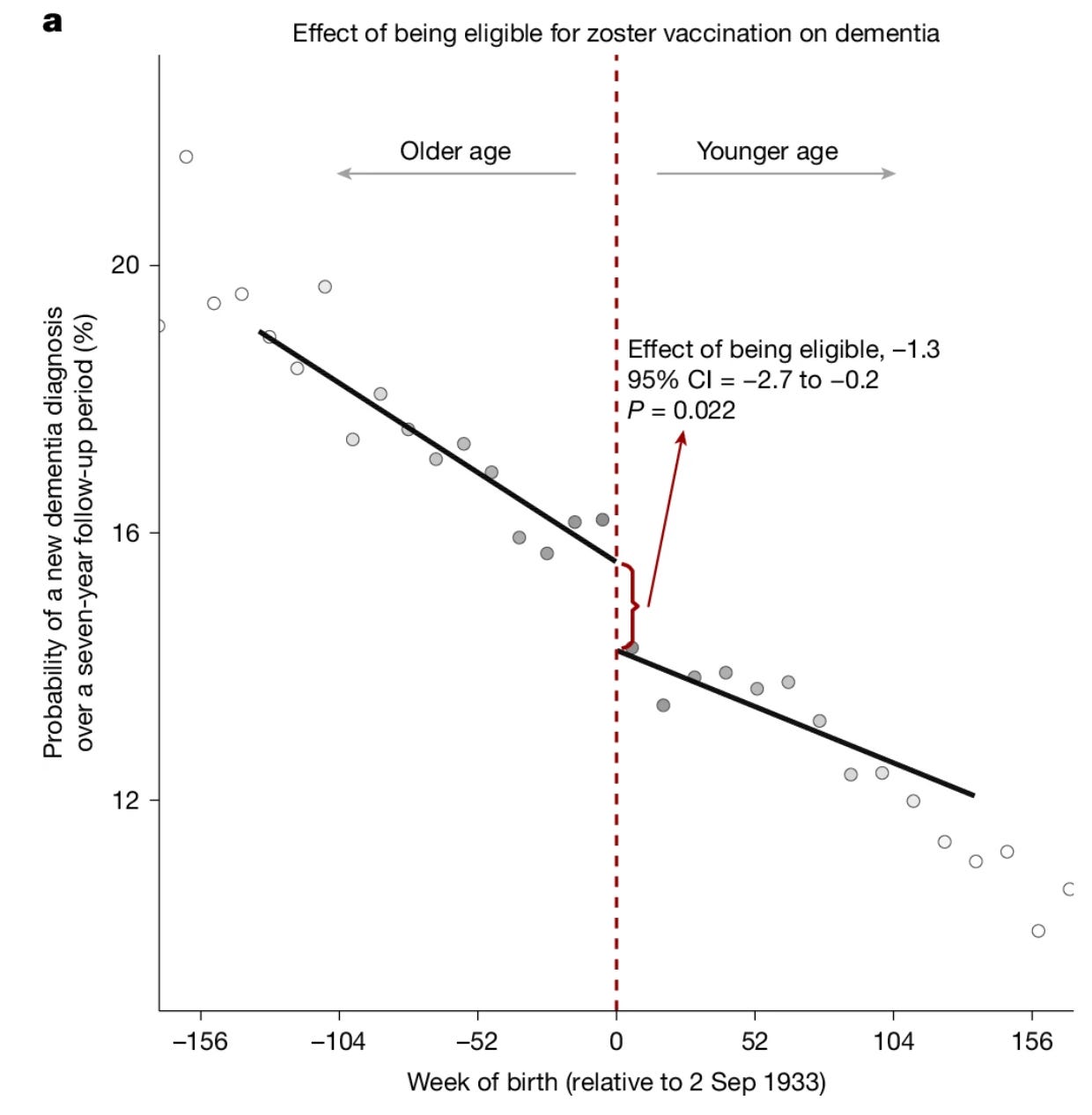

That preventing shingles reduces the risk of dementia is not crazy — Dr. Jena outlines three possible mechanisms succinctly in his editorial — but proving it is very difficult. Until now, studies of these questions have been observational ones that compare vaccinated to unvaccinated people. These studies are compromised by confounding; people who choose to get the shingles vaccine are different from those who choose not to. The new Nature study took advantage of how the vaccine was deployed in Wales, essentially a natural experiment. On September 3, 2013 the vaccine (not Shingrix, but the previous, less effective, live attenuated vaccine Zostavax) was made available to adults under 80 years of age. This allowed for comparison of a population just younger than 80 — of whom ~ 47% got the shingles vaccine — with a nearly identical population, just older than 80, of whom almost none got vaccinated.

The study showed that there was a decrement in dementia diagnoses with vaccination. This figure shows the results well.

Over the 7 years of follow-up, vaccination reduced the probability of being diagnosed with dementia by 3.5% (0.6-7.1). That’s a relative risk reduction of 20% (6.5-33.4). Pretty impressive.

This article is not meant to be a full-on critical appraisal, so I’ll be brief. I think this is an impressive study. It is about as good as you could do to address this question. Unfortunately, I do not think that it shows that Zostavax prevents dementia. Four things lead to my conclusion.

First, the absolute benefit of the vaccine in terms of preventing shingles was 2.3% (0.5-3.9). I have a hard time believing that the shingles vaccine is more effective at preventing dementia than it is at preventing shingles.

Second, my clinical experience tells me that what this data shows us is that when older people get shingles, they often have a functional decline. I think this functional decline is being labeled, in this data set, as dementia. It is even conceivable that very mild shingles (shingles not even diagnosed as shingles) is being prevented, accounting for a “dementia” effect in excess of the shingles effect.

Third, the effect on dementia prevention in this study is really only seen in women. From a pathophysiologic perspective, I have trouble understanding this without a whole lot of handwaving. If my second point explains the findings, it might explain the male/female discrepancy. Men have a shorter life expectancy than woman. Maybe at this age, men are frailer, more apt to get diagnosed with dementia without the “help” of shingles. For women, it takes more to unmask their dementia. More, like a bout of shingles. This is just a hypothesis.

Lastly, I am not a neurologist or a scientist who studies dementia, but it seems surprising that an intervention at 79 could yield great benefit in preventing dementia.

3. Churnalism

What is my problem with the Times’ article? I’ve come to think that newspapers should have a section titled, “Interesting news in biomedicine that does not impact your health at all.”2 This study would fit perfectly in this section. It is an ingeniously designed study. It is really interesting. It might impact future research. It just should not affect people’s healthcare decision making.

The conclusion as stated in the study’s abstract:

Through the use of a unique natural experiment, this study provides evidence of a dementia-preventing or dementia-delaying effect from zoster vaccination that is less vulnerable to confounding and bias than the existing associational evidence.

A total reasonable conclusion. The Times article, on the other hand, begins:

Getting vaccinated against shingles can reduce the risk of developing dementia, a large new study finds. The results provide some of the strongest evidence yet that some viral infections can have effects on brain function years later and that preventing them can help stave off cognitive decline.

We are in an era of vaccine skepticism. The causes of this are numerous, including overreach by health authorities during COVID and an HHS director who seems intent on spreading misinformation. Therefore, we — healthcare professionals, scientists, and journalists — need to be careful, recommending vaccines based on what they provide. They should not promise effects that are uncertain.

Everyone over 50 should get the shingles vaccine (the currently offered one, Shingrix). They should do this because it is proven to decrease the risk of shingles and postherpetic neuralgia. Full stop.

Conclusion

Medicine needs to win back trust that has been lost. This will be accomplished by working to deserve this trust. Journalists can help doctors and biomedical scientists by reporting advances accurately. They must not hype promise to get people to read the article. Social media directors of news outlets should certainly not be pushing alerts of articles that are probably only important to people deep in the field of research.

Addendum

After I finished writing this up, Vinay reminded me that he wrote an article about similar data on Sensible Medicine two years ago. Looking back, it turns out that he wrote about the same data when it was in preprint. Three notable things: 1. Our take on the data is almost identical. 2. Journalists (and social media scientists) are just as apt to jump on a rickety bandwagon now as they were back then. 3. I can’t believe Sensible Medicine has been around long enough to get all self-referential.

Addendum 2

This article has continued to haunt me. It was referenced on the NPR quiz show Wait Wait Don’t Tell Me last weekend. (It has still fallen short of the “liberal media trifecta” by appearing in the Times, NPR, AND The New Yorker). Then, I received an alert from the AI platform Open Evidence about the article. What I thought was our most trusted medicine AI tool now also says that the shingles vaccine prevents dementia.

Addendum 3

Please, beloved Sensible Medicine readers, spare me the invective for admitting that I get notifications from the Times.

If the New York Times wants to hire someone to write this column, my email is adamcifu@uchicago.edu.

No invective re the Times, though as I point out to my children, given how much they get wrong when you happen to read about a subject you know well (for you medicine—in our house it’s more law, politics, and finance), why do you imagine they’re more reliable on other subjects?

Another such natural experiment on recombinant vaccines:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-024-03201-5

Probably similar. Haven't looked, but if this vaccine is supposedly more effective, it should also be more effective at allegedly preventing dementia, or misdiagnosed dementia at least.

Being relatively anti-vaccine, shingles vaccines are just about the only shots I would consider getting after 50 (but probably would not with current state of evidence and my faith in my acute treatments). At the very least I would never try and convince others not to get it. The core reason is that the risks of shingles seem so incredibly high. A proxy for overall risk can be risk of PHN. Incidence of PHN seems so extremely high. Somewhere I calculated a guess that 1 in 50 people are walking around with PHN at any moment. That seems absurdly high, but if you believe the references on the course of shingles and PHN, that's in the ballpark. Does this match with anybody's experience? I think I guesstimated an NNT to prevent (through repeated vax every 10 years, for life after 50) one case of PHN is 26.

Just too many questions for me:

- I have trouble believing recombinant vaccine giant efficacy numbers. No raw trial data. At the end of the day, no data = no vax for me. I just can't do that one. The older vaccines have some long-term data at least.

- I have trouble believing PHN is as prevalent as implied.

- No credible surveillance of harms (but this is a case where I am relatively willing to take what I will presume to be greatly undereported risks, just because the risk of PHN seems so high).

- Many promising acute treatments of viral infections and PHN never get researched. For example, I know a doctor who has had great success treating shingles with ozone therapy.

- Shingles is caused by childhood chickenpox vaccines which destroyed natural boosting. We have probably worsened cumulative societal harm by just shifting the problem to old people where it is much worse. One paper flatly states that under one of two prevalent ethical frameworks, childhood vaccination for chickenpox vaccination in youth can be considered unethical because it just shifts risk onto someone else. And not only that, it doesn't even save that kid the risk. He just has to wait decades now to reap it through shingles.

- Doesn't seem sound to me to get it if you've had shingles in the last 10 years

- No talk of testing for immunity before vaccinating.

Edit:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK598509/

This paper says NNT to prevent one case of PHN over 3.5 years in trials is 350. For lifetime benefit, one might suspect about 10x that benefit perhaps? Or a little less. So maybe like NNV over a lifetime might be like 1 in 50?

Paper also states without citation: "Not all PHN is severe or lasts for years." Other references say otherwise. I can't figure this out.