What multimorbidity shows us about guideline-driven evidence-based medicine

One of the aspects of editing Sensible Medicine that I have truly enjoyed is receiving excellent, unsolicited manuscripts.1 We published one of these a couple of weeks ago by Aleksi Raudasoja titled From Guideline Recommendations to Articulated Harms and Benefits. Even better is when one unsolicited manuscript leads to another. What follows is one of those written by Mariana Barosa.

Adam Cifu

Primary care physicians are increasingly voicing concerns about the guideline-driven paradigm of clinical practice. At the root of these concerns lies a tension between what physicians think is the ideal way of practising medicine and how that ideal has been implemented: a tension between evidence-based medicine (EBM) in its fullest sense and guideline-driven EBM.

Notably, this tension between EBM and guideline-driven EBM gains full expression in primary care because primary care practice is dominated by multimorbidity – here defined as the coexistence of two or more chronic conditions, where (i) one condition is not necessarily more central than the others, and (ii) each condition may influence optimal clinical management of other condition(s).

The practical and philosophical challenges posed by multimorbidity to EBM – which collectively constitute what I call the multimorbidity challenge – have been the subject of active debate. Thus far, proposed solutions to the multimorbidity challenge focus on creating better “evidence-based” guidelines for multimorbid patients, when these patients are typically excluded from clinical trials.

However, as I will argue, guideline-focused approaches to multimorbidity are ultimately limited because they are premised on a guideline-driven interpretation of EBM. This is itself an epistemologically limited version of EBM because it belittles clinical expertise, which is crucial to manage multimorbidity.

A guideline-driven version of EBM dominates and belittles clinical expertise

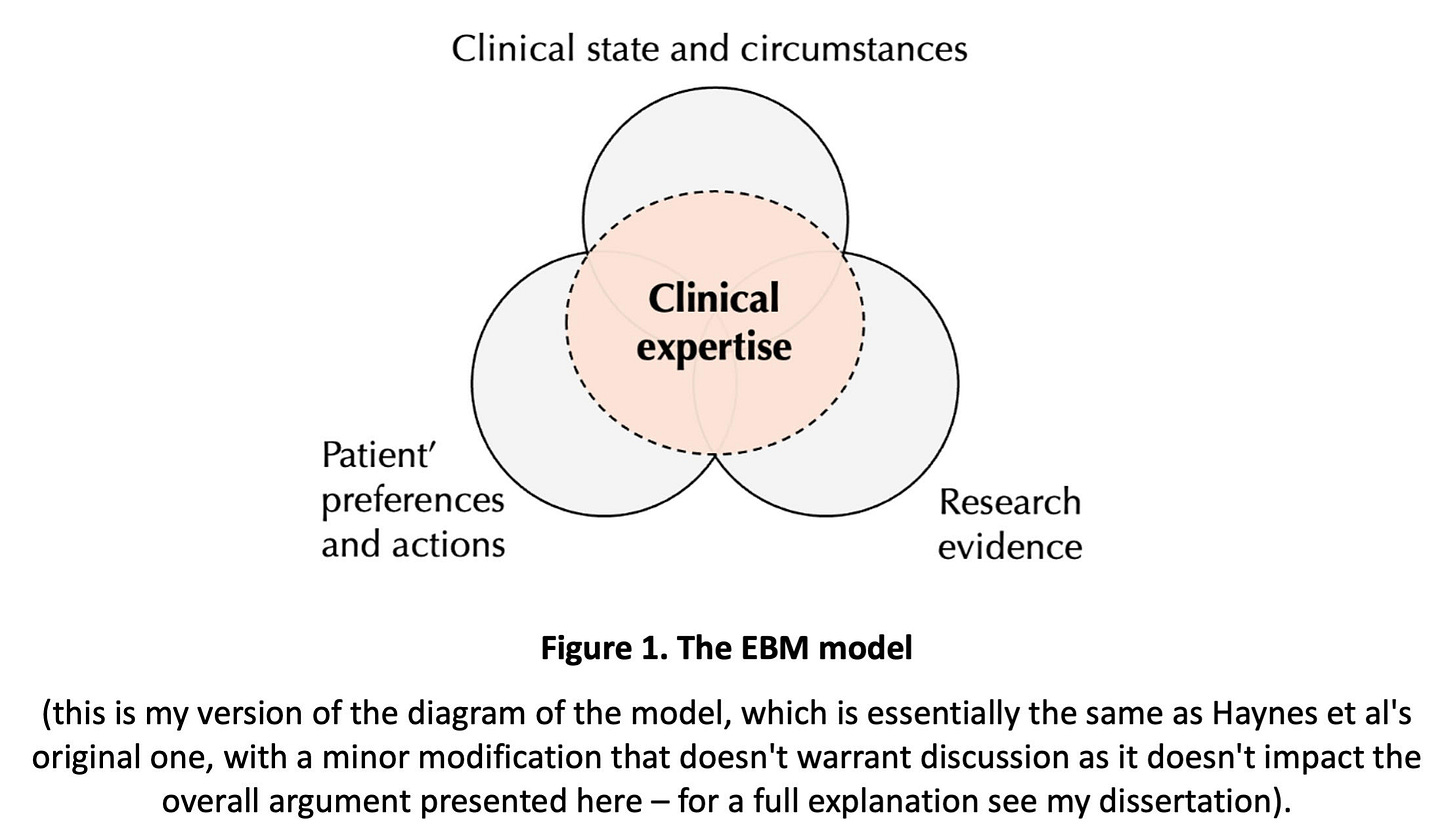

According to the Haynes et al. EBM model, individual clinical decisions should be based on three components – “patient’s clinical state and circumstances”, “patient’s preferences and actions” and “research evidence” – and clinical expertise plays a central role in integrating these components (Figure 1). This model is a refined version of the original Sackett’s model and is widely endorsed as representing EBM in the fullest sense.

The rise of EBM fueled the dissemination of guidelines for almost all individual clinical conditions. Guidelines are recommendations developed by expert panels and organisations, based on the best available evidence, typically involving a systematic review of research literature, with the intention of assisting decision-making about appropriate care for specific clinical situations.

Over time, following guidelines became synonymous with delivering optimal evidence-based care, giving rise to what I call guideline-driven EBM. However, can guidelines “handle” the complexity of medicine and be effective knowledge translation tools, i.e. effectively translate or individualise research knowledge to the patient-at-hand?

Our best research methodologies produce population-level estimates that allow us to determine average effects of interventions. Such information is then used to produce guidelines catered to the needs of groups of people, which affect individual patients only indirectly by influencing the decisions of physicians. Most guidelines focus on the management of single conditions because studies are usually designed to isolate the effect of a single intervention on a single condition outcome.

Nevertheless, EBM is about evidence-based individualised care: integrating research evidence with individual patient variables. This is challenging because there is an epistemological gap between research knowledge and practice – the knowledge-to-practice gap. This gap includes a difficulty in providing an account of inferences from statistical data to predictions concerning an individual (e.g. if a research study shows that an intervention reduces death by 50%, the average results of this trial do not tell us what will happen to an individual patient) and a difficulty in integrating patient circumstances and values in decision-making.

EBM claims to bridge the knowledge-to-practice gap with clinical expertise. The EBM model recognises that elements of judgement and expertise are necessary for the care of individual patients. Knowing how to integrate an individual person’s needs and wishes with research evidence, sorting out trade-offs, and prioritising problems, hinge on tacit elements that underpin basic human experiences and judgements. However, the guideline-driven interpretation of EBM neglects the role of clinical expertise, and thus cannot overcome the knowledge-to-practice gap.

A guideline-driven EBM amplifies the multimorbidity challenge

To fully grasp the complexity of the multimorbidity challenge, it is helpful to understand that multimorbidity is strongly associated with particular things that significantly influence the way multimorbidity is (and should be) approached, both conceptually and practically. These include advanced age, less capacity for self-management, increased social needs, polypharmacy, significant treatment burden due to complex drug regimens and follow-up plans, frailty, and – importantly – the exclusion from clinical trials. All these things affect how physicians deal with multimorbid patients.

Multimorbidity poses significant challenges to EBM. Among the epistemological challenges are the difficulty in defining and measuring multimorbidity, prioritising health problems, and dealing with a weak evidence basis. Among the practical issues is the unmanageable volume of condition-specific guidelines. For instance, the Canadian and American diabetes guidelines are now over 200 pages. In 2005, the average primary care physician would need 18h/day to follow recommendations for chronic disease and preventive care.

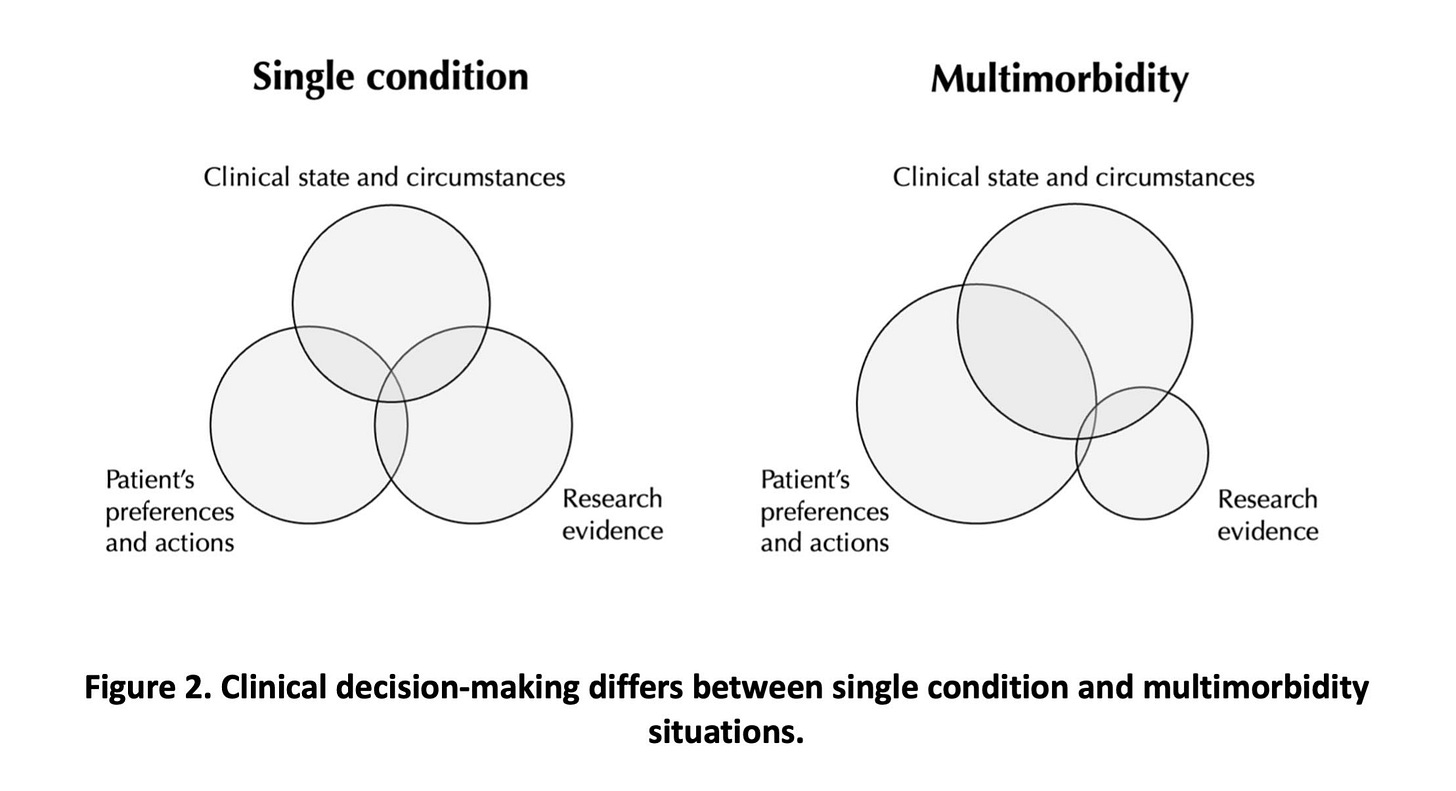

In light of the EBM model, the individual clinical state and the patient’s preferences become more salient when managing multimorbid patients than non-multimorbid ones (Figure 2).

Translating research evidence to clinical practice in a multimorbidity scenario, considering the weaker research evidence and greater influence of individual patient variables in decision-making, is harder than in a non-multimorbidity one. In other words, the knowledge-to-practice gap is wider. A guideline-driven EBM framework amplifies the multimorbidity challenge.

Guideline-focused approaches addressing multimorbidity do not look promising because both stem from a guideline-driven EBM

In the face of this growing challenge, several independent researchers have joined efforts to address it. Two distinct approaches focusing on improving guidelines gained prominence in the literature. Although both approaches position themselves within the EBM framework, they are actually rooted in guideline-driven EBM. Because this is an epistemologically limited version of EBM, any guideline-focused approach to the multimorbidity challenge is ultimately a limited solution. (In my dissertation, I discuss various limitations of both approaches, but this is the limitation that ultimately thwarts any guideline-focused approach).

Curiously, both approaches recognise the need for expertise and judgement in multimorbidity management, especially given the dearth of evidence. However, they locate it at the level of guideline panels when it should be located at the level of the individual physician.

Clinical expertise plays an augmented role in multimorbidity care

Despite being a difficult concept to explain, clinical expertise can be regarded as a kind of knowledge that enables the integration of research evidence with individual patient circumstances and preferences. It is a sort of “know-how”. It involves tacit elements and increases with experience. Clinical expertise can only be acquired and used by individual health practitioners, and its performance is contingent on clinical encounters. This is an interpretation of clinical expertise that draws on Sackett’s original definitions of clinical expertise and the EBM model.

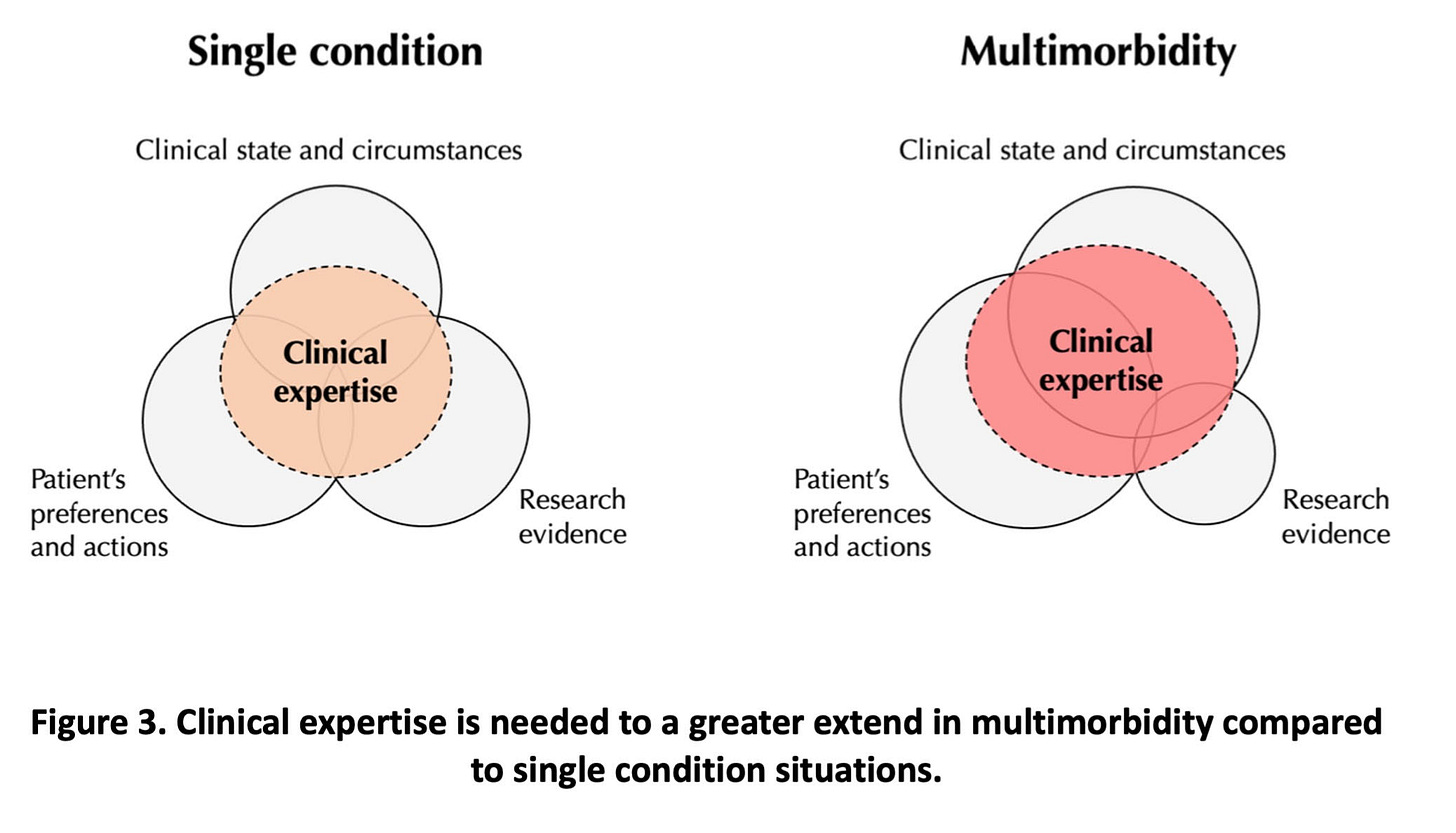

Given the prominence of individual factors in multimorbid patients and the weak evidence base, clinical expertise plays an augmented role in managing these patients (Figure 3).

Clinical expertise is needed to a greater extent for the prioritisation of health problems and for the translation of research evidence to the individual patient. Importantly, this skill is most effective in the clinical encounter, which is where the patient’s context and preferences effectively emerge (not in guideline panels’ discussions).

When there are multiple competing factors, as in multimorbidity, emerging preferences assume increased importance in sorting out a larger number of trade-offs. This learning of competing factors takes place within the clinical encounter. It is there that the patient and the physician both learn, through personal communication, what is at play for decision-making.

Conclusion

Guideline-focused approaches to multimorbidity are fighting a losing battle. Guideline-driven EBM pushes the eyes away from physicians’ clinical expertise, which is the ultimate EBM element that allows the provision of evidence-based individualised care.

While I strongly support appeals for more and better research on multimorbidity, individual patient circumstances and preferences will always tend to hold more sway in decision-making for multimorbid patients than for their counterparts. One-size-fits-all approaches like guidelines will never be able to account for the idiosyncratic nature of multimorbid patients, let alone negotiate multiple conflicting warrants for action.

Understanding the limitations of guidelines within the context of multimorbidity can affect medical education, medical training, primary care practice, and, crucially, how researchers, medical bodies and governments address the multimorbidity challenge.

Mariana Barosa is an Internal Medicine resident who completed a Masters in History and Philosophy of Science at University College London, UK, in 2023. Her dissertation is a defence of EBM as envisaged by its early proponents. By calling for more clinical expertise in multimorbidity care, she does not advocate for a blind trust in some kind of “expert judgement” but rather urges a rejection of guideline-driven EBM and revival of EBM in its fullest sense. The full version of her dissertation is here.

If you have an essay that you think would fit on Sensible Medicine, send us a draft at sensiblemedicine2022@gmail.com. We would prefer articles to be < 1200 words.

Good points well explained with the aid of the Venn diagrams.

I observe that clinicians who ignore the multimorbidity paradigm tend toward polypharmacy. The corollary is a mess with potentially unknowable outcomes. To illustrate: Drug A&B for condition 1; Drug C&D for condition 2; Drug E to counter the side effects of A/B; Drug F to counter the side effects of C/D; Add G, an antidepressant, because the patient now feels terrible! This problem grows exponentially when the patient suffers more diagnoses.

A single primary care physician may be guilty of this, but a team of subspecialists working in isolation are sure to make these errors.

Excellent article. Polyphamacy is the end result of trying to follow multiple algorithms with no one asking if the patient really needs another pill.