White Coats, Fomites, and Surrogate Endpoints

This is my second article about clothing recently. I promise I am not going to turn Sensible Medicine into a place to discuss the doctors’ style choices (“Sensible Fashion?”). However comments to my earlier article re-animated one of my pet peeves and gave me this opportunity to talk about a favorite topic, surrogate endpoints.

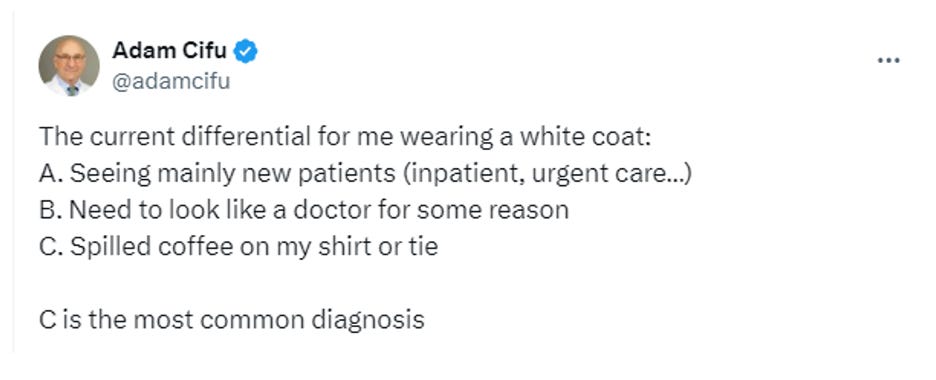

The pet peeve is people parroting the idea that wearing a white coat or a long tie — hell, even using a stethoscope — is a major threat to public health. I hear this all the time. The sentiment is often shared with the specious statement “there is data.”1 Here is one example, in the form of a response to what I thought was a particularly pithy tweet (from 5 years ago).

You should ask yourself, what data could support, in a robust way, the concern that our white coats are a threat to our patients . You might propose a RCT, a cohort study, or a case control study.

The RCT: Hospital teams are randomized to usual attire, usual attire plus white coats, or short sleeve shirts (with or without bow tie). The endpoints are hospital acquired infection, LOS, mortality, and patient (or doctor) satisfaction.

The cohort study: Doctors are identified who tend to where white coats, long ties, both, or neither. The patients for whom they care for are then followed. Outcomes could be the same as in the RCT.

The case control study: Patients with and without hospital acquired infections are identified. The doctors with whom they came in contact are then identified and analyzed to see if one group of patients was more likely to be exposed to the white-coated merchants of death.2

If you have some experience with the medical literature, you have a pretty good sense that these studies don’t exist. (I reviewed the literature, it was a painful task, believe me they do not.) So, what data are people relying on to support their anti-white coat sentiments? They are referencing studies with surrogate endpoints. Some of these studies do show that there are potentially pathogenic bacteria on coats and ties. There are a few ways you might reasonably respond to these studies. You might think, “Ikk, that’s kind of gross” or “I’m sure this will make it into the lay press!” What you should not think is, “Well, those results need to change practice.”

A surrogate endpoint is an objective endpoint that we can measure. Unlike clinically important endpoints, surrogate endpoints are invisible to the patient. Patients generally do not know a surrogate outcome is important until we tell them it is. Blood pressure, bone density, glycosylated hemoglobin, LDL cholesterol are the surrogate endpoints that fill my days.

If surrogate endpoints are invisible, and unimportant to patients, why do we use them? We use them because it is easier to show that a treatment improves a surrogate endpoint than a clinical one. It is easier to show that a drug improves bone density than it is to show that it decreases the rate of fractures. It is easier, and far less expensive, to show that a drug lowers blood pressure than it is to show that it decreases the rate of stoke. It is easier to show that a drug lowers blood sugar than it is to show that it decreases the risk of blindness, kidney failure, heart attacks, and death. Studies with surrogate endpoints may require dozens of patients and take months to years; studies with clinical endpoints often require thousands of patients and years of follow up.

The surrogate endpoints we use in research should have two qualities. First, they should be well correlated with a clinical endpoint. We know that people with lower blood sugar, better cholesterol profiles, and slower cancer progression do better than those with higher blood sugar, worse cholesterol, and more rapidly progressive cancers. Second, they should make biological sense.

The problem with surrogate endpoints is that even well correlated and plausible surrogates can be misleading. We filled chapter 3 of Ending Medical Reversal with misleading surrogate endpoints. Here are a few spectacular examples.

PVCs as a stand in for SCD (CAST)

A1C as a stand in for adverse CV effects of DM (rosiglitazone, saxagliptin, and alogliptin)

Lipid levels for CV outcomes (in non-statin drug trials like those with cholestyramine or gemfibrozil)

Progression free survival in cancer treatment (bevacizumab)

BP for CV outcomes (atenolol)

A whole bunch of surrogate endpoints we were presented with during COVID (viral particles on surfaces as proof of infectivity, respiratory droplet spread for area of infectivity,3 positive PCR for individual infectivity)

Now you might argue here that a clean white coat is an important endpoint in itself. I agree, but we are not talking about stinking, feculent clothing here. We are talking about bacteria counts on perfectly reasonable attire, counts that might have no effect on patient outcomes. I do not actually care what anyone wears with patients, as long as they have considered how their appearance will be received by all their patients. I also do not think we should mandate clothing choices without a good reason.

I should probably admit to a conflict of interest. Ever since residency, I have worn a long sleeve shirt and tie when I see patients. At the start of my career, this was because I looked like a kid, and I thought I could purchase some authority from Charles Tyrwhitt. I started to wear a white coat during the pandemic. This might have been a cognitive trick I was playing on myself to make it feel like I had an extra layer of protection. More likely it was my contrarianism — while everyone else descended into scrubs, I went hard in the other direction.4

Mostly, what I wear makes me comfortable and works for me with my patients.

Whenever people trot out the phrase “there is data”, I am reminded of the great Clash lyric from Death or Glory:

Every gimmick hungry yob digging gold from rock 'n' roll Grabs the mic to tell me he'll die before he's sold But I believe in this and it's been tested by research He who f**** nuns will later join the church

I feel like I am channeling Dr. Prasad with that turn of phrase. Working to keep his memory alive.

Remember those silly videos of runners’ respiratory droplets?

Sarah tells me I really need to note that white coat pockets are convenient, especially if you are wearing clothes without pockets.

Infection control teams, where the word plausible has been translated into causation. No arguments allowed.

Thanks for your post. Lifted my spirits after I recently lost argument with infection control team for wearing a watch during ward rounds.

"There is data" - took my 97-year-old dad with an enlarging infected neck lesion due to picking a sub keratosis to two hospitals seeing three ER doctors three days in a row. The mass is getting larger every day and red and they are keep saying there's no abscess because the data shows that the bedside ultrasound they did didn't show the fluid. I keep saying he's 97 stick a needle in it. On the fourth day, thankfully he had an appointment with the dermatologist for an unrelated problem. I sent a picture just to make sure we wouldn't get booted out. They said come right in. Soon as we were in the room, the tech took one look at it. He started shaving the back of his head when the physician walked in he excised a golf ball size area, pus poured out probably a large cup full. I went back and reviewed the data that these multiple ER doctors rely on. Yes bedside ultrasound can be helpful distinguishing cellulitis in an abscess. It is in no way 100% sensitivity. In fact one studies show it helped 84% of the time. Well, if it helped 84% of the time, what would you do the other time? There were definitely false negatives.

A cardiologist with 40 years of experience comes to the emergency room and by the way, I brought sequential photographs so this wasn't just me telling me telling them it was getting larger --they could see it visibly ??? - what if i took him to the hospital on the fourth day? He would've been admitted and maybe 12 to 14 hours later after he was septic they would've done something. This was a triumph of technology over reason.