Please do not do that research

Ten topics that do not need to be studied

It is anathema to tell people not to study things. “There is no bad inquiry” could be a mantra in academics. Even findings that seem unimportant today may shift paradigms in the future. These days, arguing for or against research can label you as a left-wing or right-wing extremist.

“Are you telling me not to study this because the results might be unsettling?”

“You’re telling me it is a waste of money studying whether vaccines cause autism?”

“How can you say we don’t need to study equity issues associated with bike helmet use in the elderly?”

You might also argue that there are reasons to do research other than answering questions. Publications are a necessary part of a successful academic career. Admission committees smile on CVs filled with publications. The science/industrial complex must be supported because it employs thousands of people doing research, or training the next generation of researchers, with the occasional side benefit of an important discovery

Yet, there are downsides to research. Time and money spent investigating one question are time and money not spent investigating another, perhaps a more important question. Not every question can be addressed; someone must prioritize what research is funded in this zero-sum game. Then there is the reality that clinicians who do research are spending less time doing clinical care. Taxpayers have underwritten their medical training; should the taxpayers then be asked to underwrite the research that takes them away from medical practice?

With this in mind, here are suggestions for research not to do. Forsaking this research sacrifices nothing, saves money, and puts doctors back to work as clinicians. We shouldn’t do this research because the results are already known, or because one more study won’t change anyone’s mind, or because a good study – a robust, non-confounded study – cannot be done.

We do not need to learn anything else about the harms of smoking. No new data will change what we tell patients. Do not start smoking. If you smoke, stop.

We do not need to learn anything else about exercise. It is good for you. You should be active, as active as possible. There may be subtle differences in the benefits of exercise based on timing, degree, and strategy, but for nearly everyone, you just need to find something you enjoy and can make part of your daily routine.

We never need another observational study about nutrition. Between confounding and the vibration of effects, these studies will not show us anything of importance. It would be wonderful if we could find diets that will make us healthier; these studies will not do it.

We never need another observational study on dementia prevention. The same arguments apply here as for observational nutrition studies. The best way to prevent dementia is to have good genes and maintain a healthy lifestyle. If we want data on dementia prevention, start an RCT. If an RCT can’t be done because the intervention could not be maintained for 10 years, well, there is your answer.

Please, no more studies about the health effects of loneliness. Loneliness is miserable, but we will never know if it makes people less healthy because it is impossible to get non-confounded data from observational studies — are you sick because you are lonely, or are you lonely because you are sick? I wish fewer people were lonely. If you have some ideas about how to achieve this, study that.

We can do without studies that look at outcomes correlated with the race, gender, or age of physicians. First, like many of the topics above, most of these studies show small effect sizes and are likely compromised by residual confounding. Most importantly, what are you going to do with the data? No more male physicians? All doctors over 40 have to work with a doctor under 30? Only race-concordant doctor-patient relationships are allowed?

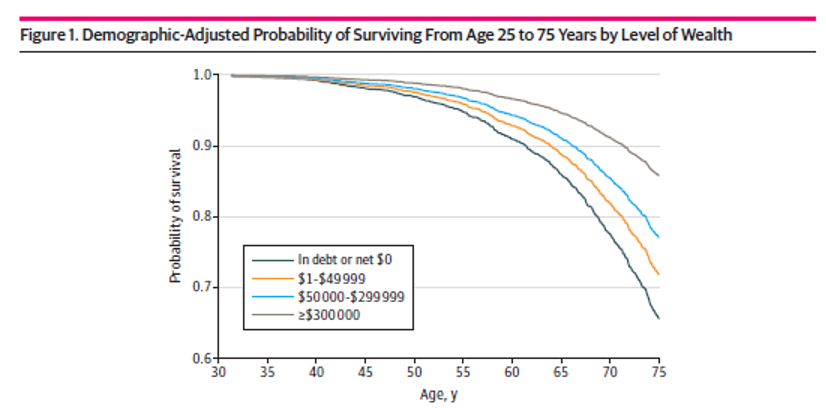

Health outcomes by socioeconomic status. Being poor, in almost any country, is terrible for your health.

So, just as smoking (which poverty is compared to in the source of the figure) is harmful, we don’t need data to tell us that poverty is bad for us. One more study will not embarrass us into finally working to decrease economic inequality. Use the money that funds these studies to do something about the poverty (or to study interventions to reduce poverty).

Do not study “innovations in medical education.” These studies almost never give us usable data because it is nearly impossible to measure an outcome.1 How do you measure the “quality of a doctor.” There is one medical education study worth reading, a case-control study with an ingenious, objective outcome.

Please, no more studies of any kind on the health effects of vitamin D. We already have thousands of observational and experimental studies on vitamin D supplementation. If your vitamin D is normal, more almost certainly does nothing; if it does has an effect, it is minuscule. Enough is enough!

And last but not least, let’s refrain from conducting any further observational studies of seed oils. I suppose this is a corollary to #3, but it is talked about enough to warrant its own bullet. Not only will we never get clean data, but no matter how good the data is, you will never convince the enemies of seed oils of anything.

Please chime in on this screed in the comments with studies you do not want to read or, because I am all about “strong opinions lightly held”, convince me that I am wrong. But, be nice, I wrote this to rile people up.

My favorite quotation about trying to tell the difference between a good doctor and a bad doctor comes from a 1981 NEJM article:

“To say that physicians are good or bad would be to imply that there are well-accepted standards of performance and random audits to judge them by; but there are none. Their nearly total freedom to determine the context of their professional activities and their own standards within this context, especially in the private office where much of medicine is practiced, precludes any rational conviction about the effects of their efforts.”

Completely agree! Once upon a time research was done to find out things, nowadays it’s done to enrich a curriculum and/or advance a career. A waste of time and other’s money.

When I was an editor at JAMA, I would tell authors don’t send me any papers that tell us that disparities exist. We know disparities exist. Send me papers that show what to do about it. I never got any.